China presents numerous opportunities for investors, but some are concerned about its debt, its property market, its old-economy companies and the possibility of devaluation. Is the bogeyman about to jump out from under the bed?

Debt?

One popular concern about China is that a rising debt-to-gross-domestic-product (GDP) ratio is a sign that a financial crisis is looming. And this ratio is widely used to gauge a nation’s financial vulnerability.

Certainly, China has a debt problem. The amount of debt per unit of GDP growth increased from 2014 through 2016. In 2016, it took 5.7 units of debt to generate one unit of GDP growth. Pouring more debt on the economy wasn’t generating much growth.

China is not ignoring its debt problem. It has taken action, shutting down excess capacity in coal and steel where it was unproductive and forcing some companies to go bankrupt. Today, it takes 3.2 units of debt to generate one unit of GDP growth.

Ghost Towns?

Another concern pertains to China’s property market. People often talk about the country’s under-occupied developments, or “ghost towns.”

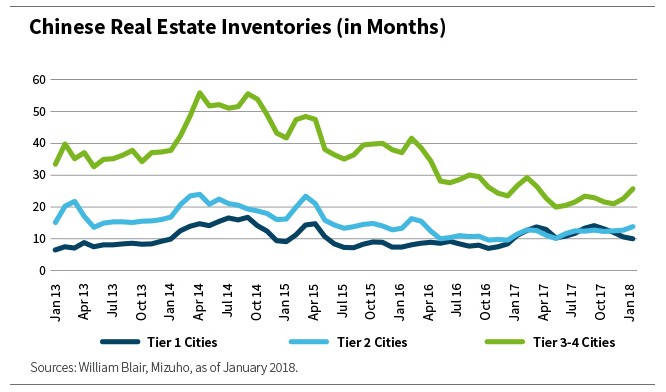

Certainly, there has been some overdevelopment in the past. As the chart below illustrates, in 2014 tier-3 and tier-4 cities had 30-month inventories, which is significant: When there were 12-month inventories in the United States, the property market collapsed.

But China depleted that inventory. It stopped construction, and levels are now average. We’re even seeing shortages in some cities, so property prices are rising.

Failing Old-China Companies?

Another concern is “old China” companies—steel, coal and other commodities—failing. But that’s not true, either. Revenue growth in old China companies dipped in 2009 and even went negative in 2015 (over devaluation concerns), as the chart below shows.

But today it’s normalized. “New China” companies—such as health care, information technology, travel and Internet—have revenue growth of 25 percent. Old China companies have revenue growth of 19 percent.

Devaluation?

Another concern investors often raise about China is the possibility of currency devaluation. Certainly, the renminbi is stronger than China would like it to be.

But I think central bankers learned their lesson in 2015. Foreign reserves were negative, and China decided to devalue to stop that.

But when it devalued, investors were surprised. Global markets gyrated and shortly after capital outflows exploded, because locals saw the value of their savings was decreasing and wanted to get their money out.

China realized it couldn’t do that again, and has been steadily accumulating reserves for some time. That removes the risk of devaluation, and the renminbi has been appreciating against the U.S. dollar, as the chart below illustrates.

What Bogeyman?

China will likely see a slight deceleration in GDP growth; forecasts suggest one of 30 basis points, to 6.5 percent, in 2018. But the quality of growth continues to improve as the government increases efforts to reduce financial stability risks and rebound the economy.

Todd McClone, CFA, partner, is a portfolio manager on William Blair’s Global Equity team.