Risk-Omicr-Off

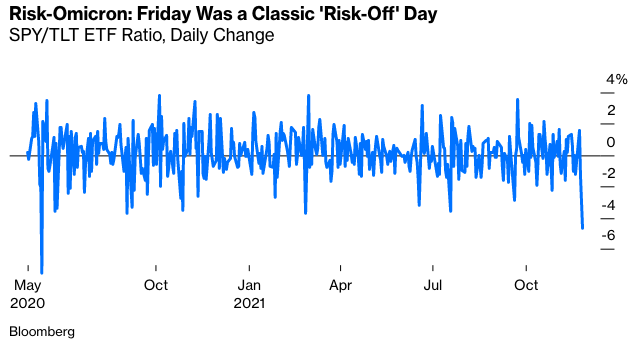

Some Thanksgiving break that was. Friday, with the U.S. markets only open in the morning as Americans digested their turkey, was the most dramatic “risk-off” day in more than a year. Not since June 2020 had U.S. stocks (represented by the SPY exchange-traded fund that tracks the S&P 500) fallen so far compared to long Treasury bonds (represented by the TLT ETF). This was a return to the old financial crisis days of “risk-on" and “risk-off” where all assets would move according to the perception of whether the environment had grown safer or more dangerous. Friday was a day when risk was off:

All readers will surely know by now that the reason for this can be summed up in one Greek letter: omicron. Thursday brought the first trickle of news stories that a new variant of Covid-19 had been identified in South Africa, while the following day brought confirmation that it had found its way into a number of European countries. There are plenty of other places to read up on this. These are the key questions as I see them, along with the state of our knowledge at present:

Omicron is more infectious than previous variants. That means that, like the delta variant before it, it could have the potential to speed the course of the pandemic once more. Any given wave, like last summer in the U.S. and the U.K. or the one gathering force in continental Europe, will be that much worse. It gives a reason to believe that the pandemic will drag on longer than previously expected, and to fear that more restrictions will be necessary.

There’s no evidence as yet that omicron is any more lethal than previous variants. There is even some anecdotal evidence, from a much-quoted South African doctor, that symptoms tend to be milder than in previous strains. But be cautioned that most of her patients were relatively young and healthy. It’s not clear whether it would have a more aggressive effect on people more at risk.

Omicron might well be resistant to current Covid vaccines, but it will take several days to be sure about this. The degree to which this variant has mutated, as many will have read, does suggest that it might well be able to infect the fully vaccinated. But for now, this is a theory.

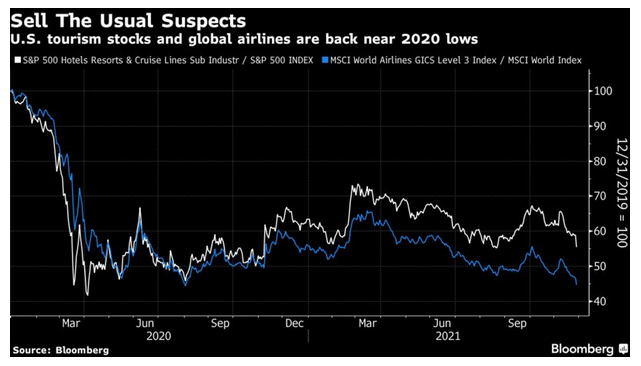

This didn’t happen in a vacuum. The most Covid-sensitive stocks had already been under pressure as cases refused to decline in the U.S. and a new wave took shape in Europe. Airlines and leisure stocks were already doing very badly before Friday, when they took the brunt of the omicron sell-off:

If this variant does prove to be vaccine-resistant, the chances are that we face a long and angry winter as governments try to persuade people to restrict their movements yet again. For those prepared to take the vaccines, however, it looks like they may be ready in a matter of months. Investors have known for some time that the real potential game-changer would be the emergence of a vaccine-resistant strain, which explains the drastic market reaction. But Big Pharma seems confident that a new vaccine should be forthcoming quite quickly, and there is no sign that omicron is particularly dangerous (although a lot of weight seems to have been put on one anecdote from one doctor in South Africa).

As a result, the indications as I write are that investors have already decided that Friday’s risk-off day was overdone. Israel’s stock market, which was closed then but open on Sunday, reflects how sentiment moved over the weekend:

The fact that the South African rand is also recovering, after a spectacular fall on Friday, also suggests that traders have decided that the risks raised by omicron have been adequately priced for now. Its rate against the Japanese yen, which had its best day since the spring shutdown of 2020 as people returned to it as a haven, has shifted spectacularly on the news:

Monday has started with very muted declines for Asian stocks, and bounces in U.S. futures and the oil price. Absent fresh bad news, it seems a fair bet that risk will be back on as the week starts, although it’s hard to see markets getting all the way back to their previous peak while important Omicron questions remain unanswered.

Omicro-Economics

What might matter more is the effect that the new variant has on monetary policy. Friday’s reaction was dramatic. If fed funds futures are to be believed, the market put its predicted second rate hike for next year in December rather than November, and now sees little chance of a third hike, even though this had been rated as a virtual certainty when traders left for Thanksgiving. The omicron news shifted monetary policy expectations to become, now, significantly easier than they were at the beginning of the week, before Jerome Powell’s re-nomination as chairman of the Federal Reserve was announced.

If we take as a base case that this slows down re-opening as much as the delta variant, but no more, then that seems reasonable. The economy does get that much more vulnerable, growth is weakened, and it is harder to justify tighter monetary policy.

But this points to the dangerous situation for the Fed. Wednesday’s raft of economic data had given Americans, and the central bank, much to be thankful for. Most strikingly, the number signing on for unemployment insurance hit its lowest since 1969. Whatever has been gluing up the jobs market, it now looks like things are moving.

Employment this strong gives ample political cover for the Fed to start raising rates. Indeed, with monetary policy so easy, it makes it hard not to start hiking.

Then there is the ongoing news about inflation. It continues to show pressure broadening and looking ever less transitory. Wednesday brought publication of the PCE deflator numbers for October, the Fed's favored inflation indicator. The numbers are slightly lower than for the CPI, but the direction of travel is identical:

While this is disconcerting, the details are worse. Looking at the Dallas Fed’s “trimmed mean” data for the PCE, which exclude the components that have moved the most and least, and takes the average of those left, we see that this version of core inflation has risen over the last six months at the fastest rate in three decades. October’s rise was a little slower than September, but still more rapid than any other month in 30 years. It is not possible to dismiss this as a transitory effect of the pandemic on a few specific sectors:

How does the prospect of further pandemic disruptions feed into the inflation picture, following the omicron news? It’s not encouraging. With social distancing making it harder to partake of services, consumer spending has funneled into goods, over-stretching supply chains. Goods inflation is running far head of inflation for services.

Further pandemic delays and stoppages would likely translate into higher goods inflation, already at its highest in four decades. Research from the San Francisco Fed amplifies the message that inflation is still being driven primarily by those goods and services that are most sensitive to the pandemic. They divided the CPI and the PCE baskets into “Covid-sensitive” and “Covid-insensitive” indexes, with the former taken from those components whose prices or quantities moved most during the first months of the pandemic. It is the sectors that took the biggest shock in early 2020 that are still leading inflation upwards:

Where does all this get us? Markets have marked down the chance of monetary tightening from the Fed, and another big pandemic wave would certainly make rate hikes very unpopular. But it looks ever more as though there is an inflation problem that another wave would exacerbate. It’s harder to see how the Fed can resist tightening.

Where The Risks Are

If the omicron news has changed the macro-environment, it also shows up in the oil price. Friday saw the most dramatic sell-off in crude oil in more than a year, apparently breaking the upward trend that’s persisted since last year’s Covid shutdown. Oil had looked overextended and had drifted down for a matter of weeks. But this was something else:

This is good news for President Joe Biden and other Western leaders, for whom rises in the price of gasoline are far more politically salient than any other form of inflation. Drivers tend to buy gasoline frequently. Even when they don’t stop, they’re accustomed to see the price advertised in big numbers whenever they pass the service station. But even with a Monday morning bounce for oil in Asia, the issues for the OPEC+ oil producers, meeting Thursday, grow all the more complicated. Several countries have eased pressure on supply by releasing strategic reserves, while OPEC is boosting production. With a new variant to dampen demand for a while, there’s pressure for the oil exporters to agree on reducing production again. They have found this difficult at several points in the recent past.

Sharp falls in the oil price generally portend trouble for emerging markets, even if they help to relieve inflationary pressure on the developed world. And indeed, emerging market currencies tumbled on Omicron Day to drop below their trough from the shutdown last spring:

If Omicron does mean further waves of the pandemic, it’s likely to cause the most damage in emerging markets, which generally have lower vaccination rates. That’s a problem, because the emerging world is bracing for a dose of austerity to pay for last year’s emergency measures, as this chart from the Institute of International Finance demonstrates:

There are further problems. The emerging world has already had to contend with higher yields and weakening currencies on a scale that hasn’t affected the developed countries, where it’s possible to print money and still enjoy low rates. This chart was produced by Robin Brooks of the IIF last week, before the omicron news, to make the point to modern monetary theorists that only countries with a long record of fiscal conservatism could print money at will without consequences. It also shows that EM could now face a severe problem:

Turkey obviously suffers from very specific issues of its own. But the sell-off of emerging currencies at the end of last week was broad-brushed. A stronger dollar, a lower oil price and a new omicron wave of the pandemic could make a lethal combination just at the point when emerging countries are least able to withstand it. While we await news from the scientists about just how vaccine-resistant and deadly this variant is, the risks to monitor concern oil and emerging markets.

Survival Tips

I’m hoping for a crowd-sourced survival tip. I’m planning a trip back to the U.K., and had the bold idea of landing and then heading straight for the birthday party of a good friend. Omicron has put a spanner in that idea. Under the U.K.’s new rules, anyone arriving must take a PCR test, and then “self-isolate” until the result arrives—which is generally about 24 to 36 hours. During that time, there is a fearsome list of rules to obey:

The difficulty I have is that all this ignores the fact that I’ll be starting in the arrivals lounge of a large international airport. Even if I get a test there (and the facilities are good for that), how do I then go anywhere else without encountering crowds of people? And as I don’t have a car waiting to drive off, how do I get anywhere without using a taxi or public transport? Going to the lengths of cutting out exercise, not letting anyone into the house, and not leaving to go shopping sounds reasonable in itself. But what on earth is the point if I’ve first mingled with the crowds at Heathrow and then made my way to my chosen location in a train, bus or taxi?

Airport terminals are some of the riskiest places for transmission. It's hard to see how self-isolation can possibly make up for the increased risk of contagion caused by my taking a plane, passing through a busy airport, and then traveling somewhere by land. The logic seems to be that if there is any point in travel restrictions at all, they need to be even more draconian (and hence damaging to morale, and to the economy). Does anybody know any way around this? What am I missing?

And if you’d like a song, in honor of the Beatles documentary, which is long but engrossing, here’s Get Back. Have a good week everyone.

John Authers is a senior editor for markets. Before Bloomberg, he spent 29 years with the Financial Times, where he was head of the Lex Column and chief markets commentator. He is the author of The Fearful Rise of Markets and other books.