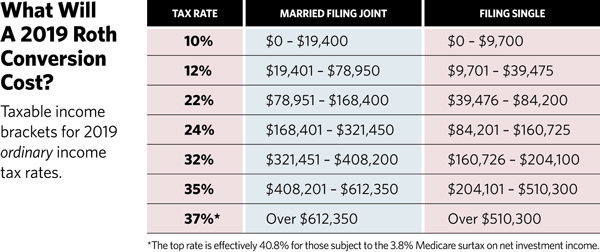

Clients will be asking you about 2019 Roth conversions as the year winds down. They’ll want to know whether they should convert their IRAs to Roths, how much should they convert and most important—how much will it cost?

What will you tell them?

For 2019, you’ll need to know how to more accurately project the tax cost of a conversion because once it’s done, it cannot be undone. Conversions can no longer be recharacterized, so once the funds are converted, the tax bill is set in stone. You have one chance to get this right.

This should be well known by now to financial advisors, but a good chunk of taxpayers did not get that memo. The tax returns for 2018 were the first ones filed under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, which, among other things, eliminated the ability to reverse Roth conversions. Poor projecting meant many people got stuck with much different tax bills than they expected for 2018 conversions. That was understandable because it was tough to compare the rates under two different tax regimes (one for 2017, and then one for 2018, when many parts of the previous law had changed or been eliminated). Even CPAs got caught flat-footed on this and really did not see the true tax effect until the returns were prepared the following year, when of course it was too late.

This year, it will be a bit easier to see Roth conversion effects since we can at least compare them with 2018’s returns—as long as most other income and deduction items are relatively similar. Yet there are still items that confound the best 2019 projections.

Some changes unexpectedly increased the tax cost of the Roth conversion. Others reduce the tax bill. That has created an opportunity for filers to capitalize by converting more funds than they might have planned to.

Here are the five most misunderstood tax effects of Roth conversions.

1. Capital Gains

This one is not new, but the larger, more favorable capital gains tax brackets left some thinking that a good portion of their long-term capital gains would fall under the 0% bracket and escape taxation. Not so! For most Roth converters, each dollar of ordinary income (including Roth conversion income, wages, interest, etc.) reduces the benefit of the 0% capital gains rate. Under the tax law, ordinary income is taxed first, which uses up the lower long-term capital gains brackets. Anyone with other income besides long-term capital gains receives little or no part of the 0% long-term capital gains rate, so don’t count on that for your tax projections. Of course, you can always offset these stock gains by harvesting losses. It can also pay to put off taking large capital gains in the same year you’re doing a Roth IRA conversion; instead, take those gains in a future year when ordinary income might be lower. For example, if most IRA funds are converted into a Roth IRA, when the taxpayer is age 70½ his or her required minimum distributions will be substantially reduced, lowering taxable ordinary income and allowing more long-term capital gains income to fall into the lower long-term capital gains brackets.

2. The 20% Qualified Business Income Deduction

This one first appeared on 2018 tax returns and still has tax planners baffled, but only when income exceeds the threshold limits.

The 2019 qualified business income taxable income limits are $321,400 to $421,400 for married/joint filers and $160,700 to $210,700 for single filers.

Most small business clients with pass-through income (from LLCs, S corporations, partnerships and sole proprietorships) fall under these limits, so they all receive the 20% tax deduction, aka “the 199A deduction,” named for that section of the tax code.

A Roth conversion, though, can throw a monkey wrench into those plans, pushing taxable income over the qualified business income limits and eliminating the 20% deduction. Yet under one of the other quirky rules, a Roth conversion can actually increase the deduction.

The deduction in general is 20% on business income from any of those pass-through entities, as long as it doesn’t exceed the qualified business income limits. Unlike others, however, this deduction, does not reduce adjusted gross income, only taxable income. But another tax rule lowers the qualified business income deduction if taxable income (in excess of capital gains) is less than qualified business income. In this case, a Roth conversion can increase taxable income and in turn increase the qualified business income deduction. But you must be careful not to convert so much that it throws income over the limit where the deduction can be lost altogether. This is a delicate balancing act.

Once income exceeds the qualified business income limits, other complex tax rules come into play that take into account what type of business it is, the amount of W-2 wages and the amount of capital investment, and these can either knock out or allow the 20% tax deduction. The deduction becomes more valuable when business income is higher, so this is important for pass-through business income clients to assess, especially those clients close to the qualified business income limits. If the client has already been disqualified for the business income deduction because of the type of business or level of income, then the Roth conversion will have no effect, since the deduction was lost even before the funds were changed over.

3. Medicare Income-Related Monthly Adjustment Amount Charges

These should be known to most advisors and clients, but the interplay with Roth conversion income is often confusing because of the two-year look-back rule. In addition, for 2019, a new income-related monthly adjustment amount bracket was added for higher income Medicare enrollees. That bracket ($500,000 and above for singles, $750,000 and above for married/joint filers) increases the charges. However, the two-year rule makes it more difficult to project this charge’s effect on a Roth conversion. The charges are based on income from two years ago (that income, modified adjusted gross income, includes tax-exempt interest and untaxed foreign income). The 2019 limits apply to 2017 income that already happened. A Roth conversion in 2019 won’t impact the income-related monthly adjustment charges until 2021. If the charges will be an issue for a higher income client, then you need to plan two years ahead to see how a 2019 Roth conversion (along with other 2019 income) will impact the income-related charges in 2021.

4. Child Tax Credit Effect

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act’s elimination of the personal exemptions for taxpayers made it hard to predict how replacing these exemptions with a new child tax credit would net out. A tax credit is more valuable than a tax deduction since the credit reduces the tax dollar for dollar. So it initially appears for some clients that the tax credit might cut the tax bill more than the personal exemptions do, unless you don’t qualify.

The credit is $2,000 per qualifying child, but this credit only applies to children under age 17, subject to the income limits ($400,000 for joint filers, $200,000 for all others). The tax credit for children age 17 or older and other dependents is only $500. While the child tax credit can certainly reduce the tax on a Roth conversion (unless the conversion is so large that it pushes income over the limits), for some taxpayers it turns out that the lost exemptions exceeded the benefit of the tax credit, unexpectedly increasing the cost of the Roth conversion. Now that advisors can look at the completed 2018 tax return, the impact of children and other dependents on a 2019 Roth conversion can be more accurately projected.

Another child-related change is the so-called “kiddie tax.” A child’s unearned income will no longer affect the parent’s tax return. The children will pay the taxes, if applicable, on their own tax returns at trust and estate tax rates. This is one of the few items that the tax law truly simplified. It will be a bit easier to project the tax on a Roth conversion for parents who no longer must include the child’s income on their tax returns. This change might lower the tax bill on conversions for these parents.

5. Alimony: No Deduction, But Tax-Free To The Recipient

Beginning for 2019 divorces, alimony will no longer be deductible, and alimony received is no longer taxable income. Pre-2019 alimony arrangements are not subject to these new rules, unless the taxpayers opt in.

Unlike many other provisions of the 2017 law, alimony stands apart in two ways. First, while most other changes in the law took effect in 2018, this one takes effect in 2019, so this year will be the first for clients who are subject to the new alimony tax rules. Second, this tax change is permanent. Most of the other changes expire after 2025.

How can these new rules impact Roth conversions? In two ways: One, the client paying the alimony cannot count on the alimony tax deduction to offset Roth conversion income, and two, the spouse receiving alimony income might be able to convert more since the alimony income won’t be taxable. Since 2019 was the first year for these changes, they will only affect those clients divorced in 2019 and those who elected to have the new rules apply to their pre-2019 arrangement. This is just something to keep in mind when projecting the tax bill on a 2019 Roth conversion for recently divorced clients.

In addition to the items listed here, there are the usual things advisors should consider when projecting the tax on a Roth conversion: year-end bonuses, as well as other onetime spikes in income or deductions; any tax benefit, deduction, credit or other provision tied to income levels, such as medical expenses (10% of the adjusted gross income limit for 2019, which is new for this year); the entire array of education credits and deductions; and real estate losses.

The 3.8% tax on net investment income can also be triggered by a Roth conversion. The conversion itself is not subject to the 3.8% tax, but it can raise income to the point that the 3.8% tax kicks in for investment income, where it wouldn’t otherwise. This should also be looked at when you are projecting the tax on a client’s Roth conversion.

Bottom Line

The point here is that advisors will have to be more precise in projecting the tax on Roth conversions since they cannot be undone. Using a tax planning program can be very helpful here since it will take all these considerations into account. But as is the case with all software, it’s only as good as your input. Working with the clients’ CPAs or other tax advisors can also be worthwhile. Either way, the client still needs the tax impact explained ahead of time. That’s why it’s called “planning.”

Also, conversions should be done later in the year when many of these factors and income levels can be better known. For some strange reason, this planning is not being sufficiently addressed by most tax preparers, leaving the tax surprise to be disclosed the following year when nothing can be done about it. This is a high-value planning opportunity for financial advisors to act on now. It can also be a reason for them to win referrals.

Ed Slott, CPA, is a recognized retirement tax expert and author of many retirement focused books. He is conducting a complimentary webcast on 2019 Roth conversions on November 21. To register, click here. For more information about other offers, see Ed Slott’s 2-Day IRA Workshop and Ed Slott’s Elite IRA Advisor Group, and please visit www.IRAhelp.com.