My parents lived through the Great Depression, so their attitude towards debt was simple: Take on as little as possible, and pay it back as quickly as possible. Thrift was a virtue stressed at every turn. We took Saturday trips to the bank to update our savings passbooks, and we consumed leftovers regardless of their age.

Nations have also valued the ethic taught to me at home. Keeping a balanced budget is evidence of efficient use of taxpayer funds; avoiding excessive debt minimizes the burden placed on future generations. Countries that become too deeply indebted risk losing control of their destinies.

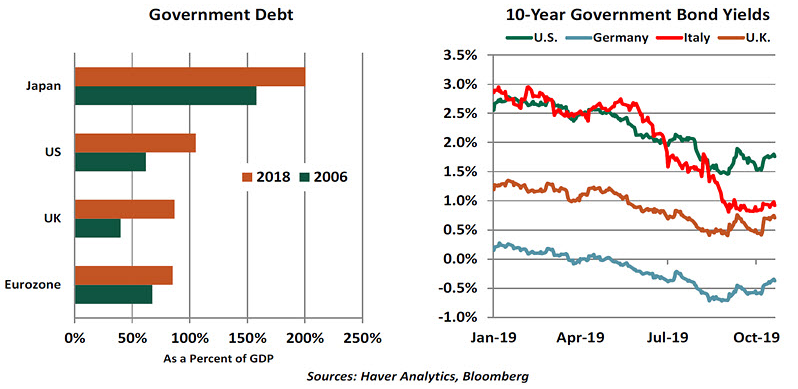

But you’d be forgiven for thinking that the world has forgotten about the virtue of thrift. Despite a ten-year expansion, the amount of sovereign debt outstanding around the globe has risen to a staggering level. What’s more, some leading economic thinkers are suggesting we should be borrowing even more aggressively. Have they lost their minds, or are they onto something?

The main catalyst behind recent increases in government borrowing was the 2008 financial crisis, which prompted substantial countercyclical spending. The expansion that followed has been long, but cumulative growth over the past decade has been modest relative to past cycles. This has made it difficult for budgets to get back into balance.

Yet even as governments have gone more deeply into the red, the cost of carrying the debt has fallen. Long-term interest rates in developed countries have collapsed this year, counter to what many expected. This makes it appear, at least for now, that the consequences of all of that borrowing are not that severe.

The proper size of deficits and debt has always been the subject of differing political perspectives. On one side are fiscal conservatives, who feel governments govern best when they govern least. They fear borrowing done by the public sector can absorb capital that could be used more purposefully by the private sector (a process known as “crowding out”).

On the other side are fiscal liberals who see the national budget as a tool that governments can employ to achieve a broad range of economic and social objectives. In many countries, there have been renewed calls for additional spending to address income inequality, climate change, and infrastructure.

The steep fall in interest rates has created common ground for the two groups. Even fiscal conservatives acknowledge that in the present situation, budget expansion is much less objectionable. This line of reasoning was championed earlier this year in a paper by Olivier Blanchard, the former chief economist at the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Blanchard’s thesis is that when the rate of economic growth is higher than the rate on government borrowing, the ratio of debt to gross domestic product (GDP) will decline over time. Viewed another way, if a government can generate economic returns that exceed its cost of capital, then additional debt is worth taking on.

With the recent strength of long-term bond prices, nominal GDP growth currently exceeds 10-year borrowing rates in most developed countries. The gap between the two has become especially pronounced in places like Germany, whose sovereign debt carries a negative yield.

This theoretical support for loosening fiscal policy dovetails with rising popular backlash against austerity. Europe, in particular, has struggled to find the right formula to generate additional economic growth; budget rules within the eurozone severely constrain the ability of governments to spend. When the IMF provides support for struggling economies, it typically requires strict budget control in return. This damages economic growth.

Opening government purse strings would also take pressure off central banks. Monetary policy continues to stretch and strain, but inflation remains below targets in most markets. Rates are low (or negative), quantitative easing programs are reaching their limits, and forward guidance is losing effect. And the low-interest-rate environment is leading some investors to become more aggressive, creating a risk to financial stability.

But there are potential problems with opening the fiscal floodgates. Firstly, the additional budget room may not always be used wisely; it could be dangerous to assume incremental outlays will produce enough incremental growth. Making additional investments in infrastructure might chin the bar, but increasing public pension benefits may not. The selection process for government projects may be driven more by politics than economics.

Secondly, as mentioned earlier, any investment done by governments has the potential to crowd out private investment. Blanchard suggests this risk is modest; business investment around the world has been soft lately, despite very low rates on corporate debt. But the merits of direct spending by the public sector vis-à-vis providing investment incentives to the private sector are worthy of careful discussion.

Finally, the notion that borrowing comes without consequences still sits uneasily with some of us. Economic growth has exceeded borrowing rates for most of the past decade, but debt-to-GDP ratios have continued to increase. Interest rates may not always be as low as they are today; the greater the debt, the greater the potential that investors will demand a premium for holding it. The more governments try to exploit interest rates that are below growth rates, the sooner this favorable borrowing window will close.

Proponents of modern monetary theory will probably accuse me of being stuck in the past. But anyone forced to eat three-week-old spaghetti will have an aversion to repeating the experience. Taking on too much debt is a similarly unappetizing prospect.

Third Time’s The Charm

This week, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) cut the federal funds rate by another 25 basis points to a range of 1.50-1.75%. This marks three consecutive meetings with cuts, and we believe it will be the last reduction for some time.

Keen readers noticed a wording change in the FOMC’s post-meeting statement. In its past communications, the FOMC indicated it would “act as appropriate to sustain the expansion.” The October statement, however, reported the committee would “monitor…incoming information…as it assesses the appropriate path of the target range for the federal funds rate.” The softer word choice of “assessing” instead of “acting” is key. Fed Chair Jerome Powell was less nuanced in his remarks after the meeting, saying monetary policy is “in a good place.”

The need for rate cuts has been the topic of much discussion, not least among the FOMC members themselves. Each decision to cut has come with dissents. The September dot plot, which charts committee members’ opinions of the appropriate level of near- and long-term rates, showed no member advocated for a prolonged cutting cycle. Roughly half the committee indicated one more cut in 2019 was appropriate, and that cut has been delivered.

The Fed’s hesitation to cut further is understandable. The economy continues to grow. The central bank’s mandate is to maintain stable prices and maximize employment. On the latter front, the economy is outperforming. The unemployment rate has held low levels of 4% or less for nearly two years. Job creation in October’s report exceeded expectations, and the labor force participation rate reached a cycle high. We see no indicators of a weakening labor market: new jobless claims are steady, hiring rates have yet to fall and wage growth continues.

Inflation has been more challenging. The Fed has chosen a target of 2% annual growth in the core personal consumption price index, which excludes volatile food and energy prices. The target is meant to be symmetric, with the actual rate moving both above and below the target. In reality, though, 2% has been the effective maximum rate observed in this cycle; inflation has rarely exceeded this level.

A confluence of factors is holding down inflation. Automation is making workers more productive; e-commerce enables comparisons that keep prices in check; inflation rates in the healthcare and higher education sectors are starting to cool. Moderate inflation is not necessarily a problem: businesses benefit from steady prices, while people living on fixed incomes will not see the value of their savings inflated away. And, as Kansas City Fed President Esther George said in recent comments, the average person isn’t concerned with slight changes to inflation rates.

Other policymakers have reason for worry, though. If inflation isn’t running above target under today’s circumstances of low unemployment and steady growth, the target may never be achievable. When the economy cools, the risk of deflation becomes more pronounced.

When discussing the current rate cuts, Fed Chair Jerome Powell has made reference to the “mid-cycle adjustments” of 1995 and 1998. In those years, the Fed cut rates slightly when the economy showed signs of slowing, in order to sustain the expansion. Just like today, there was a confluence of events that made markets nervous at the time, such as Russia’s sovereign default. The economy pulled through, and the Fed’s easing likely helped. But the parallel to today is stretched. Interest rates in the 1990s were higher. A reduction of 75 basis points was a relatively small step from a starting point of 6%, but from the current cycle’s peak of 2.5% is a substantial use of ammunition.

We expect the Fed to hold the federal funds rate steady over the year ahead. Powell did not preclude further cuts, but we predict they would have to be prompted by a severe deterioration of economic data. Meanwhile, studying past insurance cuts leads to an obvious question: Once markets normalize, will the Fed raise rates, as we saw in 1997 and 1999? Powell was clear in this answer: The FOMC will only consider a rate hike after inflation returns above its 2% target. Though inflation is recovering, it will take time to build to a sustained run above 2%.

This week’s report of third quarter U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) growth reinforces the Fed’s case to pause. As it was in the second quarter, real consumer spending was the brightest point in the data, growing by 2.9% at an annualized rate. Encouragingly, after a six-quarter decline, residential investment picked up, suggesting the Fed’s lower rates are working to support rate-sensitive sectors. Business investment continued to decline, but the factors weighing on business sentiment, like trade uncertainty and a global slowdown, are beyond the Fed’s influence.

Markets have also come to terms with a Fed pause, as the yield curve has flattened noticeably. Term premiums have been compressed by ongoing uncertainty holding back long-term investments. But a flat yield curve is preferable to the inversion witnessed earlier this year. As prospects for growth improve, we expect risk tolerance to recover, leading to yield growth in longer-term bonds. While most buyers in futures markets are not convinced the rate cuts are over, consensus is clear that any future cuts will happen at a slower pace.

The Fed’s leaders have had unenviable jobs this year. Any decision they made was bound to draw criticism. But they have risen to the challenge, acting appropriately thus far. Further cuts would signal economic weakness, and we hope they will not be needed.

Carl R. Tannenbaum is executive vice president and chief economist at Northern Trust. Ryan James Boyle is a vice president and senior economist within the Global Risk Management division of Northern Trust. Vaibhav Tandon is an associate economist within the Global Risk Management division of Northern Trust.