Nothing speaks to why someone might consider investing in a market neutral fund better than the recent performance of Vanguard’s Market Neutral Fund. During the rocky third quarter of 2015, when the Standard & Poor’s 500 lost 6.4%, the fund rose 7%. In the first six weeks of 2016, when the S&P 500 slipped over 8%, the fund rose nearly 3%.

Despite strong inflows in the wake of market volatility, John Ameriks, who oversees the Quantitative Equity Group at Vanguard, is quick to dispel any notion that the fund is a short-term escape hatch or a way to notch big gains in a down market.

“Timing should be the last thing on someone’s mind with this fund,” he says in response to a question about whether this is a good time to be investing in a market neutral strategy. “The real issue is whether market neutral makes sense in a portfolio over the long term.”

At the same time, he emphasizes that shooting out the lights in a bear market isn’t the goal here, and if the stock market is down, the fund’s portfolio won’t necessarily be up. “Investors need to understand this is a market neutral fund, not a market inverse fund,” he says. “The value here is having a return that is unrelated to other asset classes over time. We treat this fund as a diversifier with modest expectations for outperformance over risk-free assets.”

As their name implies, market neutral funds seek to neutralize market risk by investing in long and short positions in roughly equal proportion. In this fund, the quantitative management team of James Troyer, Michael Roach and James Stetler focus on identifying securities that are mispriced. Those that appear underpriced go on the long side while overvalued securities that could deteriorate go on the short side.

In a best-case scenario, stocks on the long side appreciate, while those on the short side go down. Under a worst-case scenario, the opposite would happen.

There are lots of in-between possibilities as well. In an upward-trending market portfolio, returns would be positive if long positions do better than short positions. In a down market, the portfolio would still earn a positive return if the shorts fall further than the longs. That’s what happened in the third quarter of 2015 and earlier this year.

During bull markets, people don’t pay much attention to market neutral funds because they underperform traditional equity funds, sometimes by a wide margin. In 2013, for example, when the S&P 500 rose 32%, the average fund in Morningstar’s market neutral category gained just 3%. And given that returns for equity markets tend to be positive, market neutral funds can be expected to underperform traditional long-only funds for extended periods.

But as both recent and historic performance illustrates, the benefits of playing both sides of the market fence come into sharper focus during sideways or down markets. Over the long term, the fund has the modest goal of delivering a return of 100 to 150 basis points over cash. From its inception in 1998 through the end of 2015, it’s produced an average annualized return of 3.34%, versus 1.98% for three-month Treasury bills.

More recently, the fund’s returns have beaten ultra-low interest rates by a wide margin. Over the five years ended December 31, 2015, its average annualized return was nearly 5%, compared with 0.04% for T-bills. The strong performance was one reason Morningstar named the fund Alternatives Fund Manager of the Year for 2015.

The firm noted on its website that “Vanguard Market Neutral has produced what investors want from alternative strategies: very low correlation, solid returns when equity markets go south, and, on top of that, the lowest fees of any alternatives fund.” Since October 2010, when Vanguard dropped AXA Rosenberg as a sub-advisor and became the sole manager, its 4.2% annualized return and 0.95 Sharpe ratio were the best in the market-neutral category through December 2015.

As a category, though, market neutral fund returns have struggled. For the five years ended December 31, the group averaged an annualized return of just 1.4%.

Despite relatively poor performance by the funds as a group, which is likely attributable to a combination of high expenses and poor stock selection, some research suggests the strategy can produce reasonably competitive returns during some periods. According to a December 2015 report from HedgeNordic, a publication covering alternative investments and hedge funds, an equity market neutral index produced an annualized return of 5.5% between January 1994 and September 2015, compared with 5.6% for world bonds and 7% for world stocks. Annualized volatility was slightly higher than it was for bonds, but well below that of stocks.

An Odd Duck

As an actively managed fund with a somewhat unusual mission, this one certainly deviates from the traditional Vanguard lineup. Ameriks, who oversees more than $20 billion in the 17 portfolios that partly or fully use quantitative, data-driven strategies, says that this has raised eyebrows among some investors, who believe Vanguard should stick to its indexing knitting and object to active management, even if it is quantitatively driven.

In response, he points out that some of the firm’s longest-running funds, such as Wellington, are actively managed. Until the mid-2000s, in fact, most of the firm’s assets were in actively managed funds.

“I’m a huge fan of index fund investing,” he says. “But it doesn’t offer the opportunity to outperform a benchmark. If your objective is outperforming the market, or another goal such as minimum volatility or zero correlation, you have to pursue an active approach. One of Vanguard’s founding principles is to offer funds at a low cost, and we’ve proven we can be successful active managers and still do that.”

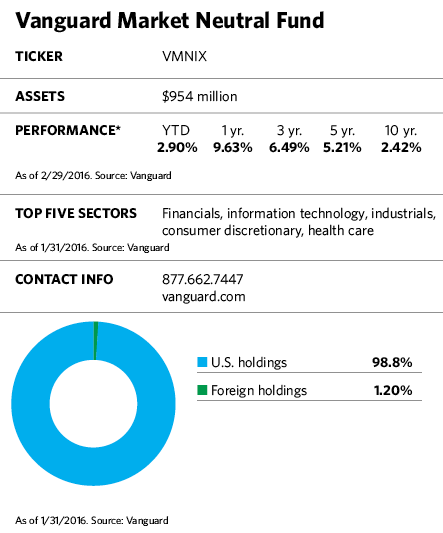

Morningstar lists the fund’s expense ratio as 0.15%, while Vanguard’s website pegs the institutional class share expense ratio as 1.54%. The higher figure includes brokerage fees and other costs associated with shorting stocks.

Although he won’t give a specific percentage allocation that might go toward the strategy, he notes that Vanguard’s managed payout fund, a fund-of-funds offering designed to provide consistent income, allocates between 5% to 15% of its assets to the strategy, depending on market conditions.

Following The Numbers

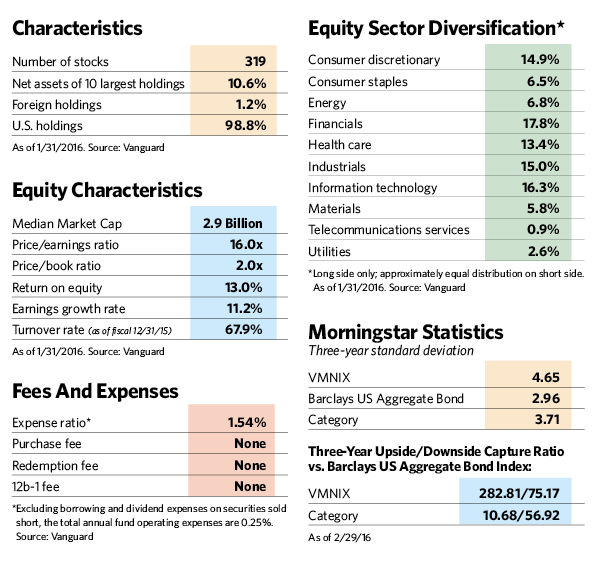

Vanguard uses a quantitative strategy to identify securities that are overpriced for the short side and underpriced for the long side. The process is designed to find growth at a reasonable price. And with a recent turnover rate of 67%, one of the lowest of any market neutral fund, it’s clear the managers are placing long-term bets.

“There’s a common misconception that quantitative investing means high-frequency trading, using statistical algorithms and reacting to every bit of market news,” he says. “But that’s not us.”

Rather than overweight and underweight securities or sectors against a benchmark, Vanguard’s market neutral strategy tries to identify risk characteristics on both sides of the portfolio so that each one balances the other out. The long and short sides of the portfolio have roughly the same industry allocation to avoid industry bets.

To generate “alpha,” the managers compare companies within industries to gain exposure to the most attractive (undervalued) and least attractive (overvalued) companies across industries. The long and short sides of the portfolio each consist of between 200 and 250 stocks. To prevent a single stock from driving performance, the managers keep a maximum company weighting at 0.5% on both the short and long sides.

The team ranks stocks relative to their peers based on earnings growth, earnings quality, management, positive investor sentiment and valuation. Stocks that score highly on those factors are placed on the long side of the portfolio, while those that score poorly populate the short side. The average price-to-earnings ratios of stocks on the long side are much lower, and earnings growth rates much higher, than those of stocks on the short side.

Ameriks points out that although the approach is data-driven, it is based on identifying market mispricings that occur because of very human tendencies, such as the one to pile into a stock with an exciting story or to overlook financially sound but less tantalizing companies growing earnings at a decent pace.

“Markets are efficient, but not perfectly so,” he says. “We think we can achieve long-term outperformance by systematically exploiting short-term inefficiencies and anomalies that result from some investors’ behavioral biases. You have to believe that such inefficiencies exist to justify an active approach.”

Investors considering the fund should note that while the minimum investment is $250,000 for retail investors, that minimum is waived for institutional investors and advisors.