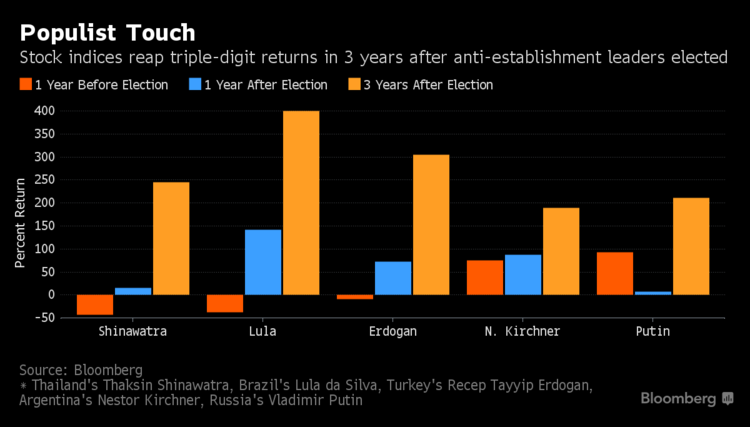

If the last two decades of anti-establishment rule are any guide, the world may be on the brink of some monster stock rallies as it takes a turn toward populism.

A look at 10 of the 21st century’s most recognized populist leaders shows that in the three years after their election, local equities soared an average of 155 percent in dollar terms. And the rallies often continued as long as a decade after the vote.

The explanation, according to Satyen Mehta, a money manager at Neon Liberty Capital Management who has researched the phenomenon, is that populists often create short-term stimulus that supports growth even as the nations’ debt burdens swell. (Their foreign bonds, it should be noted, tend not to perform nearly as well.)

Market performance under populist leaders is an issue front-and-center for investors as firebrand leaders who promise to put their people first go on the march from the U.S. to India to Turkey and the Philippines. Though economists say policies such as cracking down on imports, championing local industries and raising government spending will stifle growth in the long term, data compiled by Bloomberg shows that stock buyers can do quite well for years after a populist comes to office.

"While conventional wisdom suggests investors should be wary of populist leaders, equity markets were actually much more resilient when their policies turned out to be more benign than initially feared," Mehta said.

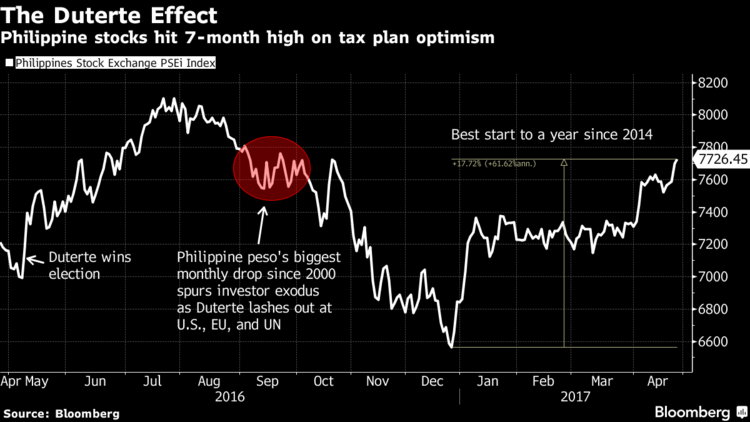

The Philippines seems to offer a textbook example of the policies that have led in the past to outsize gains. President Rodrigo Duterte is boosting spending on infrastructure, cutting taxes and enjoying the region’s fastest economic growth, even as he comes under intense criticism for human-rights abuses. And foreign stock traders are turning bullish, putting $198 million to work in the country’s stock market last month after withdrawals in February and March.

"Investors can’t afford to be off the train, for they could be missing out on a potentially sharp rally," said Noel Reyes, who helps manage $1.2 billion as chief investment officer at Security Bank Corp. outside Manila. “He’s been pursuing the reforms to sustain growth and he remains popular despite criticisms on his leadership style."

Investors in the Philippines willing to look past the extra-judicial killings that have earned Duterte the nickname “The Punisher” while drawing condemnation from Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International have seen stocks climb to a seven-month high.

Nomura Holdings Inc. recently initiated coverage of 15 Philippine stocks, citing the tax cuts’ potential boost to the banking, property and retail sectors.

Triple-Digit Returns

The pattern of outsize returns for countries run by populists has been seen from Brazil’s Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva to Russia’s Vladimir Putin, as well as in Poland, Egypt and India. Under leaders generally considered leftist, equities have done particularly well, producing 221 percent returns in three years. Right-wing heads of state saw 122 percent gains over the same period, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

The numbers get a little trickier longer term, but for countries where there’s available data stock investors saw returns of 355 percent in the populist countries over five years and 442 percent 10 years down the road.

Read more: How Do You Know a Populist When You See One?

Mehta, who helps oversee $1.5 billion of emerging-market assets at Neon Liberty Capital, knows from experience what can happen when you discount a populist. In the run-up to South Africa’s 1994 presidential election, he took an underweight position on the nation’s stocks amid concerns the ANC party and its revolutionary anti-apartheid candidate Nelson Mandela would nationalize assets and not pay the owners fair compensation.

Money managers quickly realized that Mandela wasn’t only a populist peacemaker, but a champion of capital markets. South African stocks ended up gaining 41 percent in the three years after his election as the nation’s top trading partners dropped apartheid-era sanctions and the economy rebounded from a recession and crippling drought.

New Age of Populism

To many investors, populism remains a dirty word. In March, Ray Dalio, founder of Bridgewater Associates, sounded the alarm on its global rise: by his count, at the highest level since the 1930s. Bond gurus like Franklin Templeton’s Michael Hasenstab have flocked to Latin America specifically because it’s an outlier, seemingly turning away from populism.

Jan Dehn, the head of research in London at Ashmore Group, which oversees about $52 billion of assets, said that while stimulus policies from populists often lead to a bounce in the stock market, the gains come at the expense of the country’s future.

"You may get a warm fuzzy feeling short-term, but long-term you are definitely worse off than if you had not done it in the first place," he said.

In the bond market, the pain appears much earlier. Hungary’s five-year dollar bonds lost 28 percent in the year after Viktor Orban’s 1998 election, while similar maturity notes from Thailand lost 24 percent after Thaksin Shinawatra was elected in 2001. Philippine dollar bonds are down 1.4 percent since Duterte’s election last May.

Strangely enough, data show that dictatorships tend to produce outsize returns for emerging-market debt investors.

Venezuela and Poland Pay

Venezuela has expropriated more than a half dozen foreign companies and is by some estimates caught in its own period of hyperinflation. Yet it continues to make good on foreign debt payments and boasts the world’s top stock index. (Caveat: most traders are locals desperate to hedge against the bolivar’s record collapse in the black market, and international investors would have almost no chance of getting their money out of the country at the official exchange rate.)

Poland, home to this year’s second-best stock rally, has a populist president of its own: Andrzej Duda. While his heavy-handed methods have aroused protests, including formal declarations from the EU, Duda’s party remains widely supported by Poles, largely due to the nation’s steady economic growth.

"Populist leaders tend to, by definition, do things which are popular with the masses, often by way of giveaways," Tony Hann, the head of equities at London-based Blackfriars Asset Management Ltd., who is overweight the Philippines. "This leads to improved sentiment and stronger consumer spending, which can be powerful drivers of markets."

This article was provided by Bloomberg News.