In late August, central bankers from around the world come to the Kansas City Fed’s annual monetary policy symposium. This year’s theme is “Designing Resilient Monetary Policy Frameworks for the Future.” In addressing the financial crisis and ensuing recovery, the Fed and other central banks have pulled out all the stops. This will be a chance to look back at the various elements (communications strategies, large-scale asset purchases, negative policy rates, etc.) with an eye to the future and how central banks can better prepare for future crises.

At the July 26-27 Federal Open Market Committee, Fed officials were briefed by the staff on progress made in evaluating “potential long-run frameworks for monetary policy implementation.” This was a process that began a year earlier. Given the wide range of tools used by central banks in recent years, it’s worthwhile to evaluate their effectiveness and their drawbacks. No firm conclusions were reached in late July, and nothing is expected to be settled in Jackson Hole this week. The FOMC minutes noted that any decision regarding an appropriate long-run implementation framework “would not be necessary for some time,” but the discussion has begun.

An economic downturn can be addressed through monetary policy or fiscal policy. Monetary policy is largely about changing short-term interest rates (the reserve requirement is not much of an option for the Fed), but we’ve seen other tools being used over the last decade, including large-scale asset purchases (what most people call “quantitative easing” or QE), special funding programs, and new communications strategies (forward guidance on rates). Fiscal policy refers to tax policy and to changes in government consumption and investment.

The broad consensus among economists is that monetary policy is quick to implement but affects the economy with a long and variable lag. Fiscal policy, on the other hand, has a more immediate impact but is notoriously hard to implement (requiring an act of Congress). Most economists believe that you cannot fine-tune the economy with either fiscal or monetary policy. Both can be employed to help the economy out of recession, but monetary policy should do the “heavy lifting.” Monetary policy is often viewed as ineffective in the initial response to a downturn. Lower interest rates won’t stimulate capital spending if firms aren’t confident that demand for the goods and services they produce will recover, nor will low rates encourage consumer borrowing if individuals are worried about losing their jobs. Currently, the view that the Fed and other central banks are merely “pushing on a string” still seems to be a widespread concern. However, while monetary policy efforts do not guarantee a recovery, they do help to limit the damage during an economic downturn.

Many of the Fed’s district bank presidents are worried about potential inflation in wages. Average hourly earnings rose 2.6% in the 12 months ending in July, but these officials worry that the job market has already tightened enough and, with monetary policy affecting the economy with a lag, it would be appropriate to move closer to neutral sooner rather than later. In mid-June, 6 of the 12 district banks had requested that the Fed’s Board of Governors increase the discount rate – and that was after a disappointing payroll report for May!

The FOMC minutes showed that several Fed officials worried that an extended period of low interest rates risked intensifying investors to reach for yield and could lead to the misallocation of capital and mispricing of risk, with possible adverse consequences for financial stability down the line. As the Fed employed extraordinary measures to support the economy in recent years, it has consistently monitored the fixed income market for signs of excess. It’s likely that tighter credit spreads were one reason for the initial increase in short-term interest rates last December. Recall that credit spreads widened significantly in early 2016, but that was not entirely unwelcome in the Fed’s view. It largely reflected a re-pricing (or more correctly, a “right-pricing”) of credit. While Fed officials have not spoken much about this risk, it is almost certainly a factor in the Fed’s desire to resume policy normalization.

Other Fed officials are worried that inflation will continue to undershoot the Fed’s 2% target. While prices of raw materials may have begun to firm up more recently, there’s no appreciable evidence of inflation in consumer goods (in fact, ex-food and energy, the CPI for consumer goods is registering mild deflation). Pressure in services has largely been concentrated in shelter and medical care. These Fed officials are also aware of the asymmetry of policy errors. That is, it would be much harder for the Fed to correct course if it raises rates too rapidly than if it raises rates too slowly. There’s little cost to waiting.

Above all these issues and concerns, Fed officials are also coming around to the idea that potential economic growth has slowed. The more moderate growth outlook is largely due to the slowing in labor force growth (a 1.8% annual rate from 1960-2000, +0.6% since 2000, and about 0.5% seen over the next ten years). Productivity growth has notably slowed over the last five years, but most Fed officials expect that to pick up. Regardless, the neutral Federal funds rate is lower now. Quarter after quarter, Fed officials have repeatedly revised lower their projected paths of the federal funds target rate. Their estimates of the long-term equilibrium rate have also declined. Expect these projections to edge lower again at the September FOMC meeting. Also, don’t expect any easy answers from Fed Chair Yellen’s speech at the end of the week.

What, me worry?

August 15 – August 19, 2016

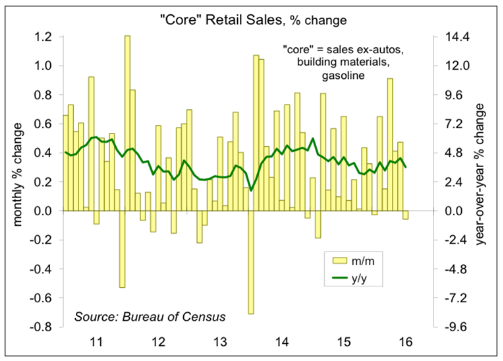

The soft retail sales results for July, combined with a lower-than-expected Producer Price Index, added to concerns that the economy may be flagging. One month does not make a trend and monthly changes in retail sales are normally erratic. Details suggest a mixed bag, with some sectors gaining over the last year, while others have softened. The bigger concern remains the slowdown in productivity growth.

Retail sales were about flat in the advance estimate for July, despite a pickup in motor vehicle sales. Ex-autos, sales fell 0.3%. Lower gasoline prices put some downward pressure on the total. Ex-autos and gasoline, sales fell 0.1%. Monthly figures can be choppy and seasonal adjustment is often tricky. Looking at the unadjusted figures for the last three months shows an odd mix. May-July auto sales were up 0.7% y/y, consistent with nearing a long-term sustainable pace (driven largely by replacement needs). Gasoline sales were down 9.9% (lower prices). Electronics fell 4.2% (lower prices, fewer new gadgets). Department store sales fell 4.7% y/y (reflecting a long-standing downward trend). Apparel fell 1.3%. Spending at restaurants and bars rose 5.2% (partly reflecting a long-term trend of taking more meals outside the home, partly reflecting an increase in discretionary income). Sales at nonstore retailers, which include internet sales, rose 13.4% y/y). These data serve to remind us that there is no such thing as “the consumer.” Wage and income growth can vary across the scale, lower gasoline prices won’t benefit those who don’t drive, and higher rents and healthcare expenses affect some households more than others – however, on average, the household sector is in good shape.

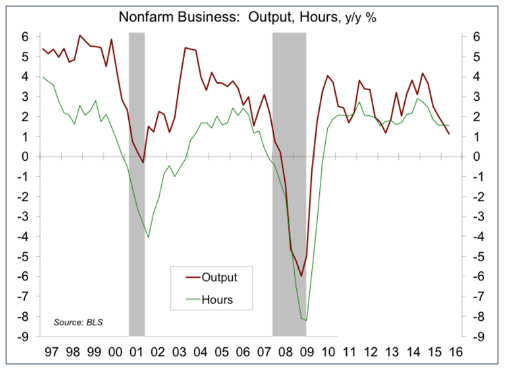

The Bureau of Labor Statistics reported a decline in nonfarm business productivity in the preliminary estimate for 2Q16, with a further increase in unit labor costs. Quarterly figures can be erratic, but the trend in output per worker remains weak – a 0.5% annual rate over the last five years.

Note that productivity growth figures have slowed less for the nonfinancial corporate sector (averaging about 1.0% per year over the last five years), but they’ve still slowed.

Faster productivity growth means that you get more output per worker. Additionally, for any given wage, it means you get more output per dollar spent on labor. A rise in unit labor costs will result in higher consumer price inflation (if firms can pass the increase along) or eat into corporate profit margins (if they don’t have pricing power). Over time, this can have a major impact on some firms and some industries.

It’s unclear why productivity growth has slowed. It could be a measurement issue, but that’s not likely. Low capital spending seems a likely culprit. Some cite federal regulations, but most business regulations are state and local. A slower turnover rate in the economy seems to be factor (as high-productivity jobs are replacing low-productivity jobs at a slower pace). Regardless of the cause, a slower trend in productivity growth would have a significant impact on how we live. Lower spending on research and development (public and private) isn’t going to help.

The signal and the noise

August 8 – August 12, 2016

It’s usually simple when the economy is booming or falling apart. The bulk of the economic data line up accordingly. However, when growth is moderate and not necessarily firing on all cylinders, the data can be all over the place. The financial markets may be susceptible to the noise in the data, but Fed policymakers will look at the bigger picture.

Real GDP growth was mixed in the first half of this year. Consumer spending growth (about 70% of GDP) was strong, even as some activity appeared to have been shifted from the first quarter to the second (likely reflecting weather and the early Easter). Other components of GDP were soft or a bit negative. Inventories, adjusted for inflation, fell in 2Q16. That could reflect business pessimism or demand may have been stronger than anticipated, but the data also show that inventories had grown less lean relative to sales over the last year. Some of the inventory adjustment may have been natural, bringing them more in line with the pace of sales. It’s hard to say for sure. Anecdotal information is mixed.

The July data on personal income and spending, along with annual benchmark revisions, show a surprising slowdown in the growth of real disposable income per capita (a 1.1% annual rate over the last six months, vs. +3.2% for the second half of 2015). To be clear, wage and income data are often revised. So this slowdown may not be genuine. Moreover, the July employment data (growth in jobs, hours, and hourly earnings) points to a pickup in personal income into 3Q16. Unit motor vehicle sales rose sharply in July, also suggesting that consumer spending growth is on track for another strong quarter (the July retail sales figures, due Friday) will help to clarify.

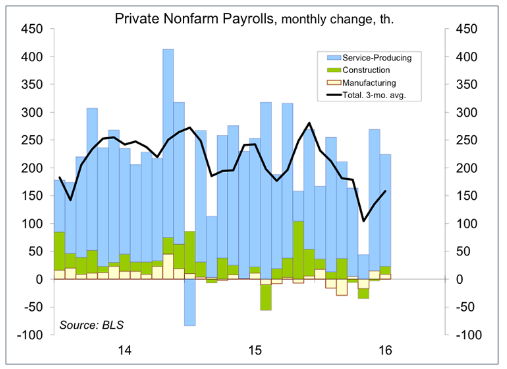

The May and June payroll figures should have taught the markets that the data are noisy. Figures for any particular month should be taken with a grain of salt. Judging by the market reaction to the July payroll figure (+255,000), nobody learned a thing. The July payrolls appear to have been inflated a bit by the seasonal adjustment (state and local government jobs up 35,000). Private-sector payrolls averaged a 158,000 monthly pace over the last three months and +167,000 over the first seven months of this year – not bad, but slower than in the last couple of years (+221,000 in 2015 and +240,000 in 2014). It’s unclear how much of that slowing is due to increased business caution and how much is due to a tighter job market.

While the financial markets don’t do nuance, most Fed officials are well aware of the various quirks and oddities in the economic data reports. What figures does the Fed look at? Pretty much everything, including anecdotal information. However, in deciding when to hike, the Fed has indicated that it will be emphasizing the job market and the inflation outlook. There will be another employment report before the September 20-21 policy meeting. The August payroll figures (along with possible revisions to July) should help to clarify the underlying trends in the job market. In the meantime, choppy and uneven economic data may whip the markets around.