Rebalancing is widely recognized as a fundamental tool for portfolio management, but it's still underappreciated. In fact, a fair amount of what's considered alpha-beating a conventionally designed benchmark-is simply returning assets to target weights.

That's hardly a secret, but it's easily overlooked. Yet even for those who focus on this portfolio tool, rebalancing is wide open to interpretation.

"I started calling [rebalancing results] behavioral alpha a couple of years ago," says Carl Richards, a financial planner who runs Prasada Capital Management. Routine rebalancing limits risk exposures, so it's a strategy for preventing large mistakes, he explains. But a number of studies suggest that rebalancing can modestly boost performance as well.

That also means it can stunt performance at times. Rebalancing a stock/bond portfolio in the second half of the 1990s, when equities were on a tear, would have crimped an investor's potential returns, for instance.

The prospects for rebalancing are quite a bit brighter over a couple of business cycles. But why should we expect rebalancing to add value (higher return, lower risk or both) at all? The simple answer is that markets don't move in a straight line.

Rebalancing exploits market cycles, which are a hardy perennial. Yet many investors don't have the discipline to take advantage of the fluctuations. And paradoxically, that behavioral bias can also explain why rebalancing helps those who do have the discipline.

A trio of finance professors suggests in a recent report that part of the return premium from rebalancing stems from the fact that most investors aren't doing it in a timely manner after substantial price changes in the capital markets.

"There is a large group of households that invest in equities but only change their portfolio shares infrequently, even after large common shocks to asset returns," write the professors, YiLi Chien of Purdue, Harold Cole of the University of Pennsylvania and Hanno Lustig of UCLA, in their study, Is the Volatility of the Market Price of Risk Due to Intermittent Portfolio Rebalancing?

This is another way of saying that the equity risk premium bounces around a lot because so many investors fail to take advantage of the volatility. As Professor Lustig told me recently, "The failure of passive investors to rebalance forces active investors to absorb more risk." That higher risk for rebalancers-the risk that prices will move dramatically-translates into higher return ... usually.

The reluctance of investors to rebalance (or rebalance quickly) when the opportunities look brightest isn't surprising. Few investors were buying stocks after prices cratered in late 2008/early 2009. Those who did likely saw better trailing portfolio returns than those investors who waited or moved to cash.

Opportunistically adjusting the portfolio mix offers rich potential, yet relatively few investors have the fortitude to act decisively. A 2004 study of 2,000 participants in TIAA-CREF retirement plans found that nearly three-quarters of them had made no changes to asset allocation during the decade through 1999. The vast majority of the households made few if any adjustments to allocations, concluded John Ameriks of Vanguard and Stephen Zeldes, a professor at Columbia University's Graduate School of Business, in their report, How Do Household Portfolio Shares Vary With Age?

The Rebalancing Bonus

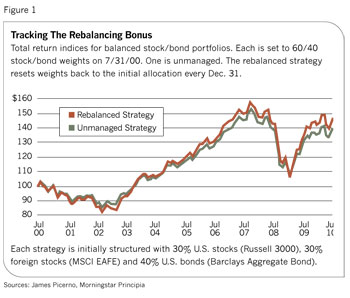

A hands-off approach to asset allocation might come at a price. Consider how a simple 60%/40% asset allocation of stocks and bonds fared over the ten years through this past July when it was rebalanced-and when it wasn't (Chart 1). The 60% equity weight is evenly split between U.S. stocks (represented by the Russell 3000) and foreign stocks (represented by the MSCI EAFE). The fixed-income portion is represented by the Barclays Capital Aggregate Bond index.

One strategy starts with the 60/40 mix and lets it run untouched over ten years. The other portfolio is identical in the beginning except that it's rebalanced back to the original 60/40 allocation every December 31. As Figure 1 shows, the rebalanced portfolio earned roughly 50 basis points a year more than its unmanaged counterpart for the decade: 3.9% versus 3.4%, based on annualized total returns.

Is a rebalancing bonus unusual? Not really. Several studies report that keeping asset allocation in a portfolio within a range in the long run tends to offer slightly better returns than when the same portfolio is allowed to drift. Does rebalancing guarantee superior results? No, although the same caveat's true for all strategies. But the odds are that you'll see better performance over time by rebalancing a multi-asset class portfolio than you would by leaving the same portfolio untended. As for how much better, several strategists guesstimate that you could make 50 to 100 basis points more. Figure 1 seems to support that view. One ten-year stretch doesn't mean much, but similar results over different periods have been documented as well.

"The actual return of a rebalanced portfolio usually exceeds the expected return calculated from the weighted sum of the component expected returns," wrote financial planner William Bernstein in a 1996 study, The Rebalancing Bonus (available at Efficientfrontier.com). In other words, rebalancing generally boosts return for a broadly diversified asset allocation over the long haul.

The technical reason is that broad asset class returns have a history of mean reversion. Stock market performance, for instance, tends to cycle around an average with an upward bias.

Does a higher return from naive rebalancing qualify as alpha? Yes, says William Reichenstein, a professor of finance at Baylor University. Rebalancing can add or subtract value, he says. Ultimately, it's a contrarian strategy, he explains. Asset classes and individual securities go in and out of favor, so "you'll get a positive alpha if mean reversion helps."

But some strategists think the return difference is linked to a particular flavor of risk. "If you can write the rule down and tell a machine to execute it, it's beta," says Larry Siegel, the former director of investment research at the Ford Foundation who is now an advisor to Ounavarra Capital in New York. By Siegel's standard, a conventional rebalancing strategy that generates a return premium is still beta. But it's a beta with a bigger helping of risk-a risk tied to the fluctuation in expected return born of mean reversion.

Rebalancing And Redesigning Indices

The effects of rebalancing can also be found in alternative index designs. One example is the equally weighted version of the S&P 500, which has a history of beating its better-known, cap-weighted counterpart. The S&P 500 Equal Weight Index (S&P EWI), which is rebalanced quarterly to maintain an even balance among securities, has gained 6% a year for the decade through this past July. That's impressive considering that the conventional cap-weighted S&P 500 logged an annualized 0.8% loss. (Like other cap-weighted benchmarks, the regular S&P 500 index isn't rebalanced.)

Real-world portfolios have also gained an edge by equal weighting. The Rydex S&P Equal Weight ETF (RSP) reports a 1.2% annualized total return for the five years through this past July, according to Morningstar Principia. That compares with a roughly 0.3% annualized retreat for the SPDR S&P 500 ETF (SPY), which tracks the standard S&P 500.

A heavier weighting in value and small-cap equities explains some of return advantage of the equal-weighted indexes, which is a natural byproduct of maintaining an even mix in everything. But some of the higher return is directly related to the rebalancing, which is a formulaic strategy that's intent on buying low and selling high.

Rebalancing is also recognized as a factor in the outperformance of other equity indices with alternative weighting strategies, such as Research Affiliates' Fundamental Index strategy, which is the basis for a variety of ETFs and index mutual funds. The oldest is the PowerShares FTSE RAFI US 1000 (PRF), which weights the largest 1,000 U.S. stocks based on their "economic footprint" rather than market capitalization. Since the ETF's launch in December 2005, it has posted an annualized 1.4% total return against an annualized 0.5% loss in the iShares Russell 1000 (IWB), an ETF that also holds the largest 1,000 U.S. stocks but is cap-weighted.

What accounts for the higher performance in the fundamentally weighted ETF? Research Affiliates emphasizes its proprietary index design, but acknowledges that rebalancing is indeed one of the factors boosting return. "Rebalancing is a relatively inexpensive way of capturing added value," advised the October 2009 edition of the firm's newsletter Fundamental Index.

That's hardly a revelation once you recognize that rebalancing can mint a gain from a collection of assets that would otherwise suffer losses by themselves. In an article published earlier this year, Michael Stutzer, a finance professor at the University of Colorado, demonstrated mathematically how rebalancing two assets that log negative cumulative returns by themselves can generate an overall gain when they're held together in a portfolio (the argument appears in his article "The Paradox of Diversification," The Journal of Investing, Spring 2010).

The message is that asset allocation and rebalancing are more powerful when you use them together. Yes, diversifying within an asset class or across asset classes is a savvy move. But such a portfolio left untended can build up high risk concentrations of winning securities and asset classes-a risk that the history of mean reversion suggests may go unrewarded for long periods. Rebalancing helps minimize that hazard. As Stutzer told me in an interview, rebalancing "improves your median return by lowering your volatility."

Higher return with less volatility? Isn't that a violation of finance theory? Not necessarily. Remember, modern portfolio theory says higher return only comes by way of higher risk (classically defined as higher return volatility). But this is true only in the original reading of the theory, analyzing one period. In this simplified world, you set the allocation once and let it ride.

Accordingly, if you design a portfolio today and leave it untouched for the next ten years, much of the gain (or loss) will be influenced by the original allocation. But introducing rebalancing throughout the same decade-long period can change the risk-return relationship.

"It's somewhat counterintuitive," Stutzer says. People tend to think that lower volatility must bring lower return, but that's not necessarily true over multiple periods, he explains.

Multi-Period Analysis

It's old hat in the 21st century to study the finer points of multiple investment periods. The concept of rebalancing through time has been around since the early 1970s, when Nobel prize-winning economist Robert Merton formally explored the idea.

Imagine an asset whose expected return is negatively correlated with the current yield on the ten-year Treasury note. Under the classic reading of modern portfolio theory, this dynamic relationship is relevant only once-during the initial creation of the portfolio. By contrast, an investor who plans on rebalancing (an "intertemporal maximizer," in the forbidding argot of economics) will continually evaluate this negative correlation and perhaps adjust the asset allocation. In other words, the investor anticipates higher returns when yields fall, and vice versa, and acts accordingly.

There are still risks in rebalancing and otherwise dynamically managing asset allocation. Perhaps the main challenge is timing. Deciding when to rebalance can be as important as how to rebalance, especially in the short term.

A trio of analysts at Robeco Asset Management earlier this year warned in a study that the choice of rebalancing dates for Research Affiliates' fundamental indices can significantly change performance results.

"For the year 2009, for example, we find that a fundamental index rebalanced every March outperformed the capitalization-weighted index by over 10%, whereas a fundamental index rebalanced every September underperformed," notes the Robeco study, Fundamental Indexation: Rebalancing Assumptions and Performance.

Is rebalancing a free lunch? A violation of finance theory? No, because the cost of reaping the potential rewards is taking on more of certain types of short-term risks-giving up expected momentum profits, for instance. It's hard to rebalance out of an asset that's on a bull market roll. All the more so if you consider that the benefits of rebalancing are uncertain in real time and usually take years to obtain. No wonder that it's difficult for so many to exploit it. Of course, that's a key reason why rebalancing offers so much potential for the relative few who are emotionally suited to tapping its opportunities.