Innovation is a staple in finance, but it's not obvious that new always leads to improved.

Wall Street's meltdown in 2008 and the Great Recession, for instance, were partly the unintended consequences of financial engineering. Can you really achieve better living through collateralized debt obligations and value-at-risk models? That's a tough sell in 2010.

Some Wall Street inventions are useful, of course, such as interest-rate swaps and ETFs. But the focus these days is on what's negative. "The concept of financial innovation, it seems, has fallen on hard times," Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke opined last year.

Good thing, too, according to several outspoken pessimists in the scientific community. Nobel Prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz fingered financial innovation as a contributing factor in the 2008 financial crisis. Meanwhile, a recent working paper by economists Nicola Gennaioli, Andrei Shleifer and Robert Vishny presents a formal model of how clever thinking on Wall Street threatens Main Street. According to the report, "Financial Innovation and Financial Fragility," financial engineering tends to promote instability because investors underestimate the risks of newfangled products.

Are the perennial efforts to update and reinvent portfolio theory any different? Is money management getting better? Have we really learned anything since the dawn of modern portfolio theory nearly 60 years ago?

On one level, it's easy to answer "yes."

The field of financial economics has made great strides in deciphering the mysteries of asset pricing. But while we know much more than we used to, it's not obvious that investment returns are superior, either in absolute or risk-adjusted terms. This is finance, not medicine or aviation. Measurable signs of progress arrive slowly, if at all.

Benchmark Analysis

To find out if the investing profession is moving forward, we start with the numbers-if there's any evidence of improvement, the proof should be in the portfolio return and risk profiles. But how to proceed? Investing strategies run the gamut in the 21st century. It's no easier to reduce the world of investing to a single measure than it is to summarize the Library of Congress in one book. A proper accounting of money management's output is complicated if not impossible. But the numbers are a good place to start.

So too is the financial advice guided by the classic interpretation of modern portfolio theory, which is the epitome of simplicity: Buy the market portfolio and customize the strategy by holding a degree of cash that's appropriate for a given investor's risk tolerance, investment horizon and so on. According to the old finance, everyone holds the market portfolio. The only distinguishing factor is the cash allocation.

How has the advice worked out? Much depends on how we define "the market." The time period matters, too. In other words, subjectivity lurks in the details. Yet we can develop useful perspectives by reviewing naïve asset allocation benchmarks as proxies for "the market."

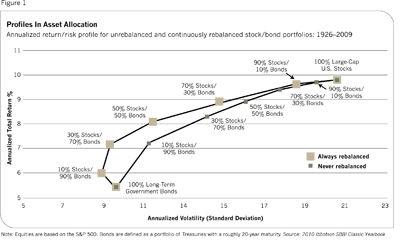

A simple example is the long-term history of various blends of domestic stocks and Treasury bonds. Unsurprisingly, higher allocations to equities are linked with higher return, according to Ibbotson Associates. But they are also linked to higher risk (the annualized standard deviation of return). History suggests, too, that mechanical rebalancing juices the results a bit (see Figure 1).

Holding a basic portfolio of U.S. stocks and bonds over the long haul generated an annualized return of roughly 6% to 9.5%, depending on the exposure to stocks and the rebalancing rule. Over shorter periods, the results can and do vary quite a bit more. In the decade through 2009, says Ibbotson, a 50/50 unrebalanced mix of stocks and bonds delivered less than 4% a year-a sharp drop from the nearly 14% return for the previous decade. Adding a bit of cash (Treasury bills or the equivalent) lessens the volatility, though it also slightly hampers return.

Looking at portfolios in this way suggests that there are several basic strategies for enhancing return. One is buying and holding a different asset allocation, or managing asset allocation dynamically. Another possibility is picking individual securities within the asset classes. But the task is tougher than a simple analysis would suggest.

Defining "The Market"

A proper reading of modern portfolio theory requires looking beyond a portfolio of U.S. stocks and Treasury bonds. In theory, the market portfolio holds all assets, weighted by market value. The true market portfolio isn't practical, of course, but we can build a reasonable if less-than-ideal proxy.

For example, imagine it's May 2000. The stock market has wobbled a bit, but it's generally been on a tear for several years and recently hit an all-time high. In fact, it was the beginning of a deep, multiyear bear market for equities. But let's say you invested in a broadly diversified portfolio at the time-at roughly the stock market's peak-with this allocation:

20% U.S. stocks (Russell 3000)

20% Foreign developed-market stocks (MSCI EAFE)

20% U.S. bonds (Barclays Aggregate)

20% Foreign developed-market government bonds (Citigroup WGBI ex-U.S.)

5% Emerging market stocks (MSCI EM)

5% REITs (MSCI REIT)

5% Commodities (DJ-UBS)

5% Cash (Citi 3-month T-bill)

Most of the allocation (80%) is evenly split between stocks and investment-grade bonds in the U.S. and foreign-developed markets, which roughly equates with a passive weighting based on market values. The remaining 20% is divided evenly across emerging market stocks, REITs, commodities and cash. For the decade through May 2010, this unmanaged strategy earned an annualized total return of 4.7% with an annualized volatility (standard deviation) of 9.2. By comparison, U.S. stocks (Russell 3000) were basically flat over the same decade with about twice the volatility. Meanwhile, U.S. bonds (in the Barclays Aggregate) rose by 6.5% over the same stretch with annual volatility of about 4.0.

Could you have done better? Maybe. For instance, rebalancing the portfolio would have boosted return modestly, depending on when and how you rebalanced. Some studies show that rebalancing over time can add 50 to 100 basis points in the long run. That implies you could have earned 5% or more a year over the past ten years with our hypothetical portfolio if you used some simple rebalancing rules.

Let's stop and consider a 5% return over the last decade as compensation for a) diversifying broadly, and b) rebalancing the mix every year or so. Not bad for a strategy that requires no skill per se.

How does that benchmark compare to the work of professional managers? We get one answer when we review the universe of 300-plus mutual funds and ETFs in Morningstar's "moderate allocation" category. For the ten years through this past May, the annualized total return ranged from a gain of nearly 18% per year to a loss of more than 8%. Far more revealing is the fact that less than one-tenth of these funds earned 5% or more per year for the decade through May.

Beating a naïve benchmark, it seems, wasn't so easy after all.

"Clever" Portfolio Strategies

Professor John Cochrane of the University of Chicago has written extensively on the evolution and trade-offs between what he calls the old and new theories of finance. A key challenge is deciding how far to stray from conventional portfolio theory. The new finance tells us that investment returns are sensitive to risk factors beyond the broad market portfolio beta identified in the classic interpretation of modern portfolio theory.

Small cap and value measures, for instance, offer a fuller explanation for the general equity risk premium against a broadly defined market-cap index of stocks. But this is merely the tip of the iceberg. Financial economics continues to identify additional risk factors. The ongoing revelations suggest that the basic notion of alpha-an active manager's ability to beat the benchmark-may be a misnomer after all. Instead, the investment landscape seems to be populated with two broad types of systematic risk factors, says Cochrane-the betas we know, and those we have yet to identify.

The new insights imply that it's time to jettison the old finance. There's now a wider menu of risk factors to consider in asset allocation. That opens the door for minting higher returns for those investors who choose to customize their portfolios. But those investors will also face down the additional hazards bound up with alternative betas.

For instance, there's a case for carving out a separate allocation for small-cap and value stocks. But there's a limit on the number of investors who can chase these investments without driving down the expected excess return into negative territory. That's probably one reason why the realized risk premiums for these stocks have evaporated at times. Similar caveats apply to other nontraditional risk-pricing strategies as well, such as taking advantage of the momentum effect, the liquidity risk premium, merger arbitrage, etc.

Modern portfolio theory's standard advice, in other words, is still worthy when you're considering how to modify your investment strategy (if at all). The old finance advises that the broad market portfolio is optimal for the average investor over the long term. But no one is average. Cochrane says the first step in synthesizing the old and new world orders in finance is asking how one investor's risk profile is different from others. For instance, if one investor works in the oil industry, there's a case for minimizing, eliminating or even shorting energy stocks in his equity allocation.

The next step is diversifying broadly across asset classes and avoiding taxes, Cochrane says. "Then we can be clever."

Tactical Allure

The steep, synchronized losses of virtually everything during the financial crisis of 2008 convinced many advisors that intelligent investing and risk management mean more than developing a strategic asset allocation and holding fast to the mix. For many, tactical asset allocation (TAA) and related techniques are the solution.

But how much can a person do? However much you might want to dynamically manage the investment mix, you can't totally replace a long-term strategic asset allocation, says Leslie Strebel, a principal at the Strebel Planning Group in Ithaca, N.Y. "You have to employ both."

That means the investor must do some active asset allocation to defend himself in case his buy-and-hold strategy stumbles in the short run. The bear market in stocks in 2000-2002 convinced Robert Leahy of Leahy Wealth Management Group to use a more active approach for managing the asset mix. Yet he also recognizes that tactical asset allocation has a price. "It's much more time consuming and involves a lot more thought and research than a buy-and-hold modern portfolio theory portfolio," he says.

And, of course, you may be wrong in your tactical decisions, says Byron Green of Green Investment Management, which blends tactical and strategic asset allocation disciplines in client portfolios. And even if TAA adds value, it won't come easily if you remain broadly invested, he adds. The more diversified a portfolio, the more difficult it will be to boost the return. That can lead an active investor to make bigger tactical bets in his attempts to beat a broad asset allocation benchmark, Green says. On the other hand, the investor can also lag the unmanaged benchmark if those bets go wrong.

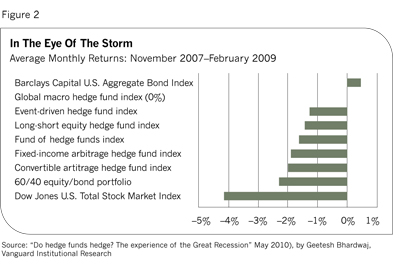

The financial crisis suggests that we should keep our expectations about active management modest. During the 15-month stretch through February 2009-one of the worst periods in the modern history of capital markets-several leading hedge fund categories suffered along with the stock market, according to a study by Vanguard (see Figure 2). To be fair, the stock market fared worse, and global macro funds as a group excelled at minimizing the losses.

But a simple 60/40 portfolio of equities and bonds would have softened the blow too. "Most of the hedge fund categories failed to provide significant diversification beyond that of a 60/40 portfolio of stocks and bonds," the study concludes. So it's debatable whether clever hedge fund managers added any value over the naïve strategies from the old finance. Some did, but many didn't.

Superior Risk Management

Advisors not only chase higher return with these strategies but also hope to curb the threat of devastating loss. TAA can do that, but so can a dedicated portfolio-protection overlay. Yet not all protection strategies are created equal, warns Jerry McCollis, chief investment officer at Brinton Eaton, a wealth management firm in Madison, N.J.

For instance, it's easy to buy a put option on the S&P 500. If the market tanks, the put's price will soar, offsetting some or all of the associated loss. The problem is that when the stock market recovers, the put's value plummets. And the protection is costly over time, says McCollis.

"We're still looking for the ideal answer, but we found something close enough to put clients into," he continues. McCollis points to structured notes issued by Deutsche Bank based on the firm's Emerald Index, which fluctuates with the spread between daily and weekly volatility for the S&P 500 (customized notes based on the Emerald Index can also be tied to other market indices). The note generates a small profit when daily equity volatility is higher than its weekly counterpart, which is the trend over time. The risk management kicks in if daily volatility surges-as it usually does during market crashes. In that case, the note's value rises sharply, helping offset losses in stocks.

What's the risk? A sustained move in the same direction by equities at some point would boost weekly volatility over daily levels, triggering a loss for the note, perhaps a steep one. That's considered unlikely, but not impossible. Another danger is counterparty risk-institutions are taking the other side of the trade of this volatility swap and if they go bankrupt the notes could suffer big losses, perhaps to the point of becoming worthless. Otherwise, the note is expected to generate a small amount of income over time as long as weekly volatility remains under daily readings. That trend pays the expenses and perhaps dispenses a small amount of income over the long haul.

Meanwhile, McCollis is reluctant to say that modern portfolio theory failed or that traditional asset allocation no longer works. "It still does well what it was designed to do," he emphasizes-providing risk management over the long haul while delivering a reasonable return. But conventional asset allocation in late 2008 suffered a blow that it wasn't designed to withstand. The limitation suggests looking elsewhere to smooth over diversification's rough edges. Is the Emerald Index solution an answer? So far, so good, McCollis reports.

Maybe Wall Street's financial engineering has its advantages after all. But the core lesson in the old finance still applies: Risk and return are closely linked. Yes, the new finance tells us that risk is multidimensional and that asset allocation should be tailored and, to some degree, actively managed. That's a big change from the old finance, which saw broad, unmanaged market beta as the primary risk factor.

Yet the market beta still casts a long shadow on return as a general rule. In the short run, we can do better, according to the new finance-or worse. Keep in mind that investors who beat the market are financed with losses from those who trail it. Returns are still a zero sum game in the new finance.

The old finance no longer has a monopoly on deciphering markets, but it's still a mistake to think that its lessons are worthless.

James Picerno is editor of The Beta Investment Report and author of Dynamic Asset Allocation (Bloomberg Press).