The two deadliest words in economics are in Latin: ceteris paribus, or all else equal. In natural sciences like physics and chemistry, researchers can construct experiments to ensure that all else is equal. Economists can’t do that. So when building models, they generally include the crucial words ceteris paribus. This is an assumption, which may well not cohere in the real world.

Bear these words in mind when examining the current debate over the valuation of U.S. equities. They look extremely expensive by almost any measure that compares them with their own sales, dividends, earnings or cash flow. But the yields on U.S. Treasury bonds hit an all-time low earlier this year and remain at levels that historically would have been regarded as unimaginably low. To some extent, all else equal, lower interest rates should justify paying more for stocks; they mean that bonds, the prime alternative to equities, are more expensive, and they also mean that the future earnings stream from equities can be discounted at a lower rate, making them more valuable.

The questions, then, are to what extent, exactly, do lower bond yields justify higher equity valuations? And critically: Are all other things equal?

The debate gets fresh urgency because the cyclically adjusted price-earnings, or CAPE, ratio, as promulgated by Robert Shiller of Yale University (and covered in Points of Return earlier this week), is currently higher even than it was on the eve of the Great Crash of 1929. The CAPE compares share prices to average inflation-adjusted earnings over the previous 10 years to even out the effect of the economic cycle, and has been famous ever since Shiller used it to predict the bursting of the dot-com bubble 20 years ago.

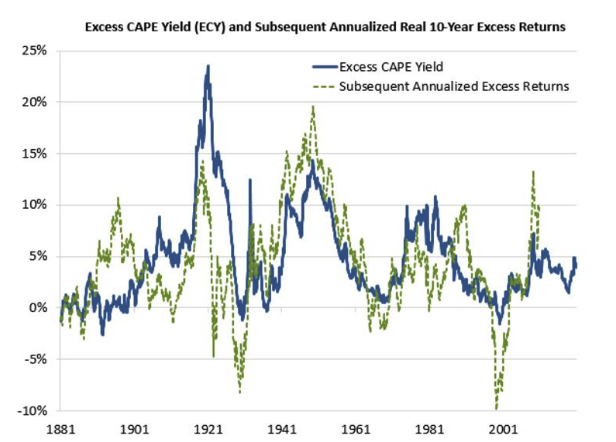

This week, Shiller went into print with Laurence Black and Farouk Jivraj with his suggested tool for handling the gap between the CAPE and interest rates. What he calls the “Excess Cape Yield,” or ECY, is a very simple spread. It expresses CAPE as an earnings yield, rather than a multiple, and then subtracts the 10-year interest rates. As he shows on his website, this measure has usually done a great job of predicting subsequent returns over the following 10 years. And on the face of it, this measure suggests that the U.S. market should be in line for average real annual returns of about 5% per year for the next decade. That would not hurt at all:

That said, this still isn’t an argument to buy the U.S. rather than somewhere else. Repeating the exercise for other countries, Shiller and his colleagues found that the ECY looks compellingly cheap in many other places:

The ECY is close to its highs across all regions and is at all-time highs for both the UK and Japan. The ECY for the UK is almost 10%, and around 6% for Europe and Japan. Our data for China do not go back as far, though China’s ECY is somewhat elevated, at about 5%. This indicates that, worldwide, equities are highly attractive relative to bonds right now.

After Britain has spent half a decade shooting itself in the foot with the Brexit saga, it makes sense that it might now be compellingly cheap. Beyond that, the ECY has the great virtue of conforming with common sense. It seemed like the collapse in interest rates amid historic levels of help from central banks bailed out the stock market, and that is what the ECY says:

a key takeaway of the ECY indicator is that it confirms the relative attractiveness of equities, particularly given a potentially protracted period of low interest rates. It may justify the FOMO narrative and go some way toward explaining the strong investor preference for equities since March.