Let’s assume that you have to invest in bonds. There are obvious reasons why you might not want to do this at present, with historically low yields, but many investors have no choice but to make large allocations to fixed-income. How best to do it? And how to make some sensible decision between bonds without incurring too many costs?

Answering these questions runs afoul of two issues. First, indexed investing doesn’t provide the same simple answer in bonds that it does in stocks. Weighting by market capitalization, in bonds, means allocating the most money to the companies or governments that have borrowed the most which, all else equal, means tending to put more funds into more indebted issues. Second, history is of little help when trying to make decisions, because the trend has been so fixed for the last 40 years. That makes it harder to trust any sensible strategies that might emerge from looking at the last four decades’ data. They might merely be reflecting the conditions of the current regime. As there is good reason to believe that this regime is in the course of changing, the available data might not be helpful.

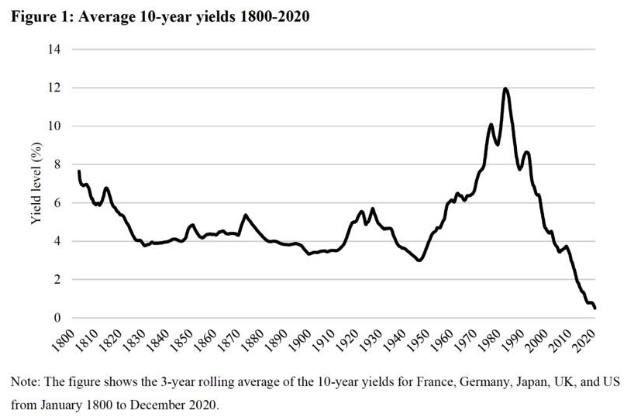

Now a paper from by Guido Baltussen, Martin Martens and Olaf Penninga, all part of the quantitative investment team of Robeco, argues that classic factor investing, of the kind generally known as “smart beta” when applied to equities, can also work for bonds. Crunching data all the way back to 1800, the paper contends it can continue to do so even if the bond market starts a steady upward trajectory after a protracted fall. The authors don’t have good enough information on the embryonic bond markets of 1800 to provide all the number-crunching that is possible on the Bloomberg terminal today, but they had enough data on France, Germany, Japan, the U.K. and the U.S. to put together this chart of the global 10-year yield over 220 years. If possible, the last decade looks even more aberrant than we thought it was:

The Robeco team used their data to test three familiar smart beta factors for bond portfolios over time. As their data set widened, they were able to test more factors. The three they looked at, all familiar from equities, were:

• Momentum — the tendency for winners to keep winning and the losers to keep losing. Robeco looked at momentum over the last 12 months minus momentum over the most recent month, as is common for equities, and applied the same measure to bonds, buying issues with momentum and shorting those that lacked it.

• Value — buying securities that are cheap relative to their fundamentals and waiting for them to catch up. In equities, this can be done with a variety of indicators, such as price-equity multiples, price to book value or dividend yields. For bonds, they applied two measures: bond yields relative to inflation (so high real yields showed up as good value), and comparing the bond yield to T-bill or other short-term yields — a strategy that many would call a carry trade.

• Low-Risk — in equities, this refers to the baffling tendency for low-beta stocks, which are less sensitive to the market, to do better over time (even though the market itself tends to do well). In the paper, the academics tested a strategy of buying bonds that had little sensitivity to the market.

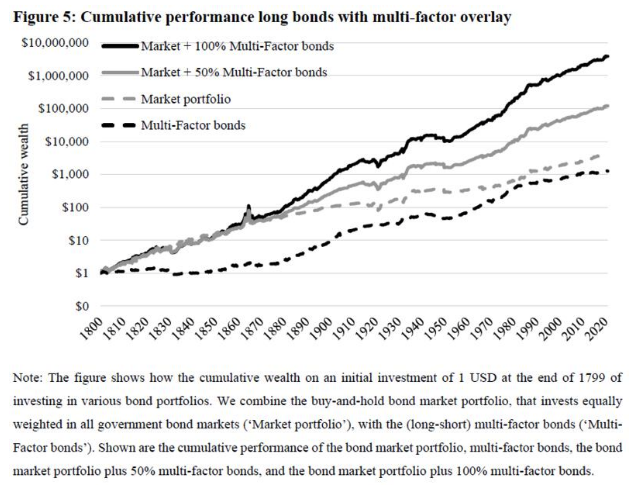

The available data increased as time progressed. The test for momentum goes back to 1800, and includes extra countries later in the sample. In all cases, they found positive returns from choosing bonds using the factor. Also, these factors aren’t greatly correlated with each other. Thus, adding a long/short factor investment to a straightforward market-cap weighted investment in the bond market adds value over time. Having spared you a lot of numbers, which are in the paper, here is the picture:

This looks great. But can it really work regardless of whether yields are rising or falling? Apparently it does. In the following chart, we see the performance of “multi-factor” bonds in years when yields are up, and when they are down. Both have gained much the same over the full 220 years, and neither has had a serious protracted downturn.

Baltussen put this in numeric terms, saying the team had found “outperformances of 3.9% in periods of yield rises and 3.0% in periods of yield declines.” In other words, factor performance tends to persist also when yields increase. So it looks as though they’ve found a way to improve on the market returns on bonds, year in and year out.

All of this looks a little bit too good to be true, which is never a good sign. Why should factors have this strong and enduring an effect on buying and selling of bonds? Baltussen suggests that it shouldn’t be that surprising. The factors all come ultimately from flaws in human nature, which is a constant. The momentum effect, for example, is based in our behavior and our tendency to overreact, and it is visible in equities, commodities and currencies. Bond markets are strongly driven by sentiment around central banks and core macroeconomic indicators. But then we have seen over the past week that emotion on these matters is prone to overshooting and exaggeration, even if the tendency isn’t as egregious as it can be in hot stocks.

Another complaint common to the burgeoning production line for such research in equities is that many of the factors identified by academics are abstruse and over-defined to fit limited data sets. In this case, government bonds are a reasonably well defined universe, and the data set is big, but there are bound to be questions over numbers that go so far back in history.

In any back test, we are also looking at a factor that nobody had identified and tried to exploit. If people buying and selling bonds issued to finance the Napoleonic wars or the U.S. war of independence had had access to this research, then it is conceivable that these anomalies would have been eliminated earlier. Much more conceivably, the effects could start to go away if bond investors start systematic factor-investing in a big way, and the idea gets marketed to ETF-issuers and pension funds.

In areas like this, the disciplines of academic research can probably do the job. Other academics will pummel the data, and we will see whether it is really this easy to exploit anomalies in the bond market. Meanwhile, the research is practical as well as fascinating, and it is a fair bet that ETFs will be aiming to use it before long.

Building A Bridge

President Bill Clinton won the last truly dull and predictable U.S. presidential election, in 1996, with the forgettable slogan that he was “building a bridge to the 21st century.” Whatever else happened subsequently in Clinton’s eventful second term, this particular pledge went seriously unfulfilled, at least in a literal sense. The American record of undertaking big infrastructure projects in the quarter-century since 1996 has been terrible. Presidents of both parties have tried and failed to get some bridge-building done amid widespread indifference.

How big a deal is it, then, that there might just be a bipartisan deal to spend almost $600 billion on infrastructure — meaning mostly the most basic physical assets, like roads, bridges and tunnels? Even if this looks like quite an achievement for President Biden (as there just aren’t the votes in Congress for a truly liberal wish-list of spending), it had little obvious direct impact on bond markets. U.S. stocks have had a good few days, with the S&P 500 back at an all-time record. The infrastructure narrative probably helped a bit, just as the earlier political difficulties weighed on the market.

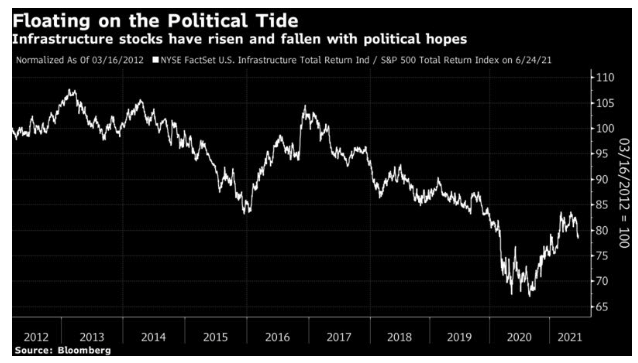

In terms of direct impact, this deal should certainly improve the fortunes of infrastructure groups, many of which are concentrated in energy. The NYSE Factset U.S. Infrastructure index has tended to rise and fall with its political prospects over the last decade, which has meant that it has generally dropped compared to the market:

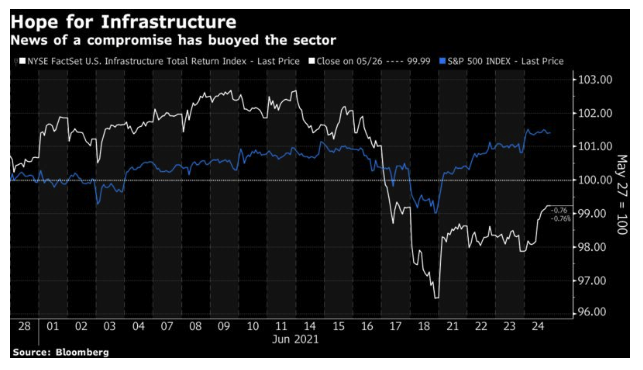

It had surged after the “blue wave” election hopes, and dwindled as the legislation appeared to move off track. This is what happened over the last month:

To go further the deal will have to survive opposition from factions on both sides of Congress. But as things stand, it is another big dollop of money that will create a nice multiplier in terms of jobs and investment, with no new taxes to create fiscal drag. It may not be terribly responsible economic policy, but it should be good for the short-term prospects of the stock market if it stands up.

Longer term, making a deal on this issue makes it easier for Republicans to dig in their heels and say no to other items on the Democratic wish list, which is why many more left-wing Democrats are uncomfortable with it. But trying to make this deal does at least reduce the risk that nothing at all gets spent. So it is fair to say that the news really is market-positive as it leaves a Goldilocks scenario where at least some spending happens, but a wild dose of tax-and-spend is avoided.

The politics of the next few months, however, leave many possibilities open. If a compromise falls through, Biden can say he made his best attempt to reach a bipartisan deal, and then use that as cover for a more concerted attempt to ram through sweeping measures with only 50% of the Senate. Abolishing the filibuster also becomes more possible. And, of course, if even this deal cannot make it, the risk that the whole endeavor falls through (something the market doesn’t want to see) grows much greater.

This was a positive development. There is ample opportunity for more positivity, or negativity, over the months to come.

Survival Tips

One tip is that you should probably give up and take the day off if you have a big family event to attend to. My daughter graduated from high school today, it was a wonderful and emotional occasion, it took place in the physical world rather than Zoom, and it made rather a big bite out of the day. Maybe I should have used up a day of vacation.

The song they played before the ceremony was wonderful. I’ve recommended it before: Lovely Day by Bill Withers. It’s been one of the theme tracks to the pandemic. Have a lovely day everyone, and a great weekend.

John Authers is a senior editor for markets. Before Bloomberg, he spent 29 years with the Financial Times, where he was head of the Lex Column and chief markets commentator. He is the author of The Fearful Rise of Markets and other books.