A child’s gender may presage how his or her parents will save for college, a new survey says.

A child’s gender may presage how his or her parents will save for college, a new survey says.

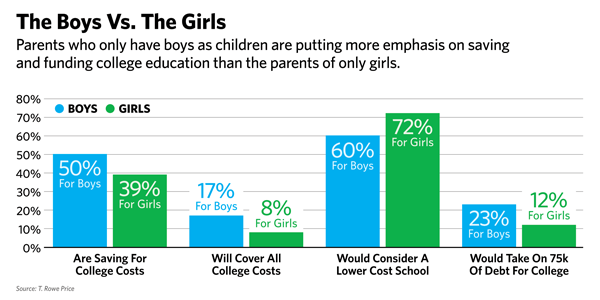

Parents who only have boys as children are putting more emphasis on saving and funding college education than the parents of only girls, according to a national survey of parents of children aged 8 to 14 that was sponsored by Baltimore-based T. Rowe Price.

While 50 percent of the parents of all boys said they had saved for college expenses, only 39 percent of the parents of all girls said the same.

Researchers surveyed parents—both single parents and at least one member of two-parent households—in 1,014 households across the nation. Of these, 15 percent were households with only girl children, 24 percent with only boy children and 61 percent with children of both genders.

Among parents of all boys, 83 percent report contributing on at least a monthly basis to college savings, compared to 70 percent of the parents of all girls.

The data was released at a time when the issue of saving for college for female students is of increasing importance: Among students in the nation's colleges, women outnumber men by about a 3-to-2 ratio, according to a spring report by the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center.

Two professors who read the survey report said the results point to a gender gap in financial planning that often isn't recognized.

Two professors who read the survey report said the results point to a gender gap in financial planning that often isn't recognized.

“I think there’s a lack of understanding the big picture at work here in terms of the many issues girls will face growing up. Not saving an equal amount or more for their girls leads directly to the pay disparity, the income disparity and the wealth gap faced by women in their careers,” says Jocelyn Wright, assistant professor of women’s studies at the Bryn Mawr, Pa.-based American College “The lack of overall financial awareness compounds many of the stereotypes that affect men and women today.”

“If, today, you asked parents straight up on the street whether they’d pay more for a boy to go to school than they would for a girl, I don’t think you’d find anyone who would say yes,” says Jamie Hopkins, associate professor of taxation at The American College. “This isn’t something that most people are doing openly or intentionally.”

Among other survey results, 17 percent of all-boy parents said they would cover all of the college expense, compared to only 8 percent of the parents of all girls.

When asked whether their parents were saving for college, 68 percent of boys responded in the affirmative, compared with only 53 percent of the girls.

Roger Young, a Baltimore-based senior financial planner with T. Rowe Price and parent of three children, said that researchers didn’t set out to explore the gender disparity in educational savings, but collected enough data to post statistically significant results for families with only boys or girls.

While the data seems to confirm some of the suspicions harbored by social activists and suggests some degree of gender discrimination in the way families save for college costs, other issues may underlie the savings discrepancy, says Hopkins.

“It’s possible some of this is explained by demographics,” he says. “If certainly families have one boy, they might not have another child. If the same families start out by having a girl, they may try again. That’s still tied to gender discrimination.”

Hopkins argues that parents may also be operating on assumptions that financial aid will be more available to young women.

Survey respondents also expressed more favoritism toward boys in terms of student loans, according to the report.

Parents of only boys in the survey were more willing to personally take on debt to send their sons to school, with 23 percent of all-boy parents willing to take on $75,000 in loans to send their sons to school, compared to just 12 percent of the parents of all girls.

Twenty-nine percent of the parents of all boys said they would let their children take on $50,000 or more in student loans, compared to only 17 percent of the parents of only girls.

“Previous studies have shown more women coming out of school with higher amounts of student loan debt than their male cohorts,” says Wright. “It impacts their ability to establish financial footing.”

Hopkins notes that, from an early age, women seem more inclined to pursue low-paying careers than men—a trend that makes it harder for them to pay off loans.

“The present value a man gets from attending college is typically a lot higher than a woman gets from going to college, largely because of the majors they pick,” says Hopkins.

While high ratios of men and women seek business administration degrees, men are more focused in high-paying fields like computer science, electrical engineering and communications engineering, while women selected lower-paying fields like education, social work and counseling, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

“The male degrees pay twice as much. If parents are making an economic decision, it makes sense that they’ll pay more for those who will end up earning more,” says Hopkins.

The parents of only boys were less likely to consider a lower cost alternative to their schools of choice. While 72 percent of the parents of all girls said they would consider sending their daughters to a less expensive school to avoid student loans, only 70 percent of the parents of all boys said they would do the same with their sons, according to the report.

“Parents are putting their girls into preconceived categories based on out-dated assumptions, like college education isn’t as important for young women, but the world has moved on,” says Wright. “These ongoing stereotypes lead to negative consequences. We know more girls than boys are going to college, we know that more women are becoming breadwinners for their families. But we forget that financial stability is still more important for women than it is for men because women will live longer on average.”

The survey also found that parents are willing to compromise or sacrifice some or all of their retirement in order to help fund their children’s college education. More of the parents in the survey were saving for their children’s college, 53 percent, than were saving for their own retirement, 49 percent.

Yet parents of boys are more likely to prioritize college savings over retirement. According to the survey, 68 percent of the parents of all boys say that saving for their children’s education is a greater priority than retirement, compared to 50 percent of the parents of all girls.

Boys, at 45 percent, were more likely to agree that their education is more important than their parents’ retirement compared to girls, at 27 percent.

Young says that there is evidence that boys are more confident about their college savings than girls.

“It certainly looks like a pattern,” says Young. “Three years ago, we asked the children whether they thought their parents were saving for college, and we saw a similar gap between girls and boys. In 2014, 52 percent of boys and 43 percent of girls thought their parents were saving, so that’s somewhat of a consistent finding.”

Wright says advisors are uniquely positioned to address these issues and to bring them to the attention of their clients.

“I think advisors do have a social mission to address these types of inequities,” says Wright. “In creating relationships with our clients’ families, we’re not just working with the parents, but with the children as well to create continuity within the client relationships. Advisors have an opportunity to help young women.”

T. Rowe Price sponsored the survey, which was conducted by Research Now in January.