I’m going to repeat myself. I don’t know whether the current dose of inflation will prove to be transitory or not, but what should worry everyone is the weight that is being put on the proposition that it will soon be over. For the latest evidence, take a look at the regular monthly survey of fund managers published by BofA Securities Inc. Based on interviews with investors who between them manage an ungodly amount of money, it tells a clear story.

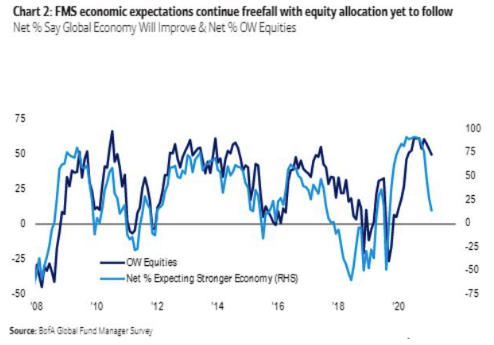

First, fund managers are growing much more negative about the prospects for a strong economic revival. BofA describes economic expectations as being in “freefall.” And yet the overwhelming majority of them say they are overweight in equities. This has barely begun to budge:

All else equal, you’d expect weakening economic prospects to damage bullishness for equities. But all isn’t totally equal, and there is a difference between the corporate sector and the economy. If earnings can survive, then so can stocks.

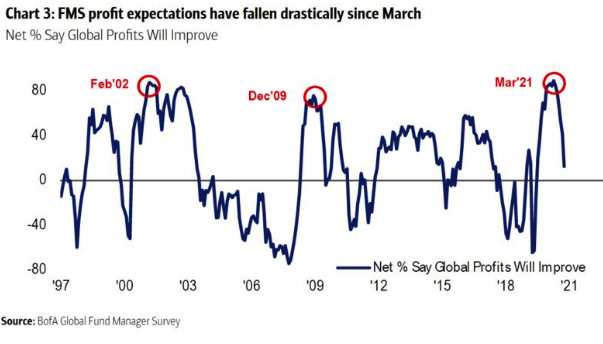

Unfortunately, hopes for profits are also sagging, dramatically:

That leads to the glum conviction that people are overweight equities in a declining economy because of their confidence that bond yields will stay low, and leave them with no choice. TINA, or There Is No Alternative, raises her ugly head again. A weak economy can help keep bond yields low and prop up stocks. But rising inflation could mess that up badly.

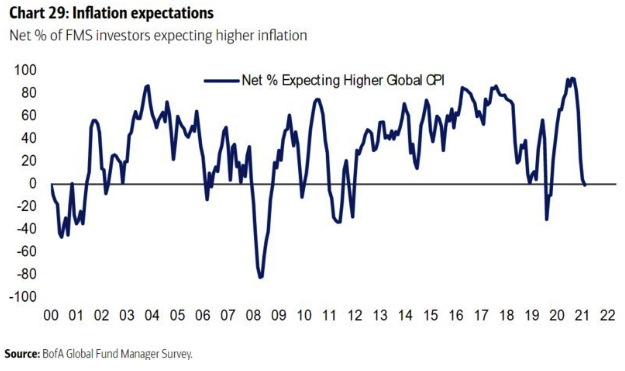

And so we find that stocks are in fact being propped up by a total collapse in those who believe that global inflation is heading higher. That belief had been persistent since before the pandemic took hold. Now, on balance, there are no more inflationists than deflationists:

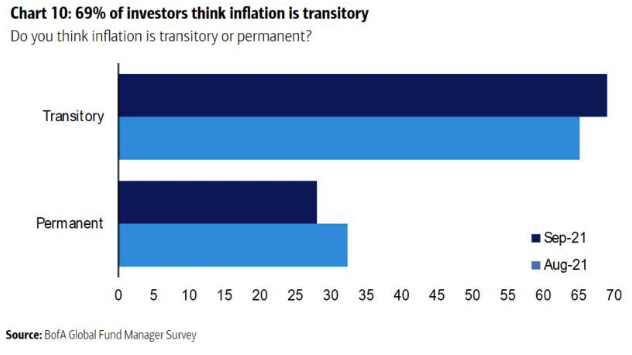

BofA handily asked some more questions, and also discovered that “Team Transitory”—those who believe that inflation will soon go away—is indeed in the majority, and its ranks are growing:

They may well be right. But it’s uncomfortable that quite so much is riding on it.

CoronaNumbers

That leads to another question. Why so bearish about the economy all of a sudden? The obvious answer begins with a Greek letter. The delta variant has plainly had an impact on the latest round of economic numbers, and it would make sense if it had also had an impact on economic expectations. As summer started, the general expectation was that North America and western Europe would be fully back to “normal” by now, and they aren’t.

But a look at the data on the virus suggests that rather than a reaction to the pandemic, we are instead witnessing one of the purest and most deadly expressions of political risk on record. The toll of the virus is increasing, and its progress has confounded much expert prognostication once again. But it is political differences, which generally have more to do with some kind of tribal allegiance than with any ideology, which are driving negative outcomes. It looks to me as though investors perceive it that way, and that the coronavirus itself is no longer their greatest concern.

That is made clear by another handy chart from the BofA survey, which has been noting what percentage of managers view Covid as the biggest tail risk out there since last April. Here is the latest one:

Delta did indeed register on investors’ radar, but their concern has already peaked and begun to decline. The big issues for them concern inflation and bonds, rather than another pandemic wave. And if we look at experience in Europe, where many BofA respondents are based, you can see why. NatWest Strategy in its regular roundup of Covid-19 data publishes charts of excess deaths, arguably the most reliable tally of the ultimate human cost of the pandemic. Below is the chart for England, the country where both the alpha and delta variants made their first big impact on the Western world. The scale is in terms of difference from the norm; the blue dotted line is the base line, or the number of deaths we would normally expect for that time of year. Anything above the red-dotted line suggests deaths in excess of anything that can be explained by normal random variation. It tells quite a story:

Statistically, last year’s first wave was indeed as horrific as it felt at the time. But the delta wave has caused no identifiable increase in deaths beyond what we would usually expect. Indeed, the English death rate in recent weeks has been unusually low. So although it does create problems, these data seem to confirm that the contagion is under control in the U.K.

Now to compare with the U.S. In the following chart, I have indexed both the U.S. and the U.K. death rates to their peak during the first wave in the spring of last year. This seems to be the fairest way to gauge the relative severity of each wave for each country. The difference is startling:

Until this summer, the experience of both countries, which are roughly as wealthy as each other, was very similar. Both had a bad first wave, a worse second wave thanks to alpha, and then a sharp decline. But when it comes to deaths, the U.S. third wave is now almost as bad as the first, while the U.K. isn’t having a third wave at all. How to explain this?

Epidemiologists have the rest of their lives to answer that question. But using Occam’s Razor, we know that the vaccine came along early this year, and the vaccine would certainly explain the sharp decline in both countries’ death rates. And if we look at how many people have actually been vaccinated in the U.K. and the U.S., we have the inkling of an explanation:

Nothing went wrong with the supply of vaccine in the U.S. in the early summer. At this point, all adults in both countries have had ample opportunity to get vaccinated if they wish, free of charge. That is why the problem appears to be political. People in both countries are free not to get the vaccine. Americans are choosing to make far more use of that freedom. That leads to large pools of unvaccinated people in parts of the country, which makes it easier for the more contagious variant to take hold, and gives it more opportunities to infect the vaccinated as well.

A working hypothesis might be that there is enough “herd immunity” within the U.K. to keep the death toll from the virus within bearable bounds. But in the U.S., the choice has been made to eschew herd immunity and allow the deaths to continue.

Looking at the numbers for Texas and Florida, the two large states where Republican governors have vocally refused to enforce social distancing and where there is great skepticism toward the vaccine, the results are startling. I compiled the following chart the same way as the earlier comparison of the U.S. and the U.K., indexing both states’ death rates to the peak in the first wave, which in the southern U.S. came in August last year. As with the U.S. and the U.K., the pattern was remarkably similar until early this summer. Since then, Texas has endured a clear-cut third wave. The experience in Florida is remarkable, and suggests that there is more to the problem than vaccine hesitancy:

Unlike virtually anywhere else in the Western world, Florida is in the midst of a third wave much worse than the first two. Without getting too political, this makes the state’s current policies toward the virus very hard to understand; and also makes the current death toll look like the result of deliberate decisions, both by politicians and individuals. This is only a hypothesis, and it looks as though there is more to the Floridian third wave than resistance to vaccines, but numbers like this help explain why investors are calm.

As with inflation, much rests on this. At present, it appears, markets are priced on the assumption that the virus doesn’t come up with a variant that resists current vaccines. Let’s hope that’s right.

Survival Tips

As you read this, Yom Kippur has started. For 25 hours, the world’s Jews put themselves through a Day of Atonement, thinking about where they have gone wrong in life, and what they can do to put it right; and fasting throughout the time to help concentrate the mind.

Yom Kippur is on the face of it a ritual that few if any people would ever want to take part in. But it retains great power, and it’s observed by many who don’t normally consider themselves religious. To give some idea why people put themselves through this, I’d like to recommend this song by Daniel Cainer. And a good fast to those who are atoning.

John Authers is a senior editor for markets. Before Bloomberg, he spent 29 years with the Financial Times, where he was head of the Lex Column and chief markets commentator. He is the author of The Fearful Rise of Markets and other books.