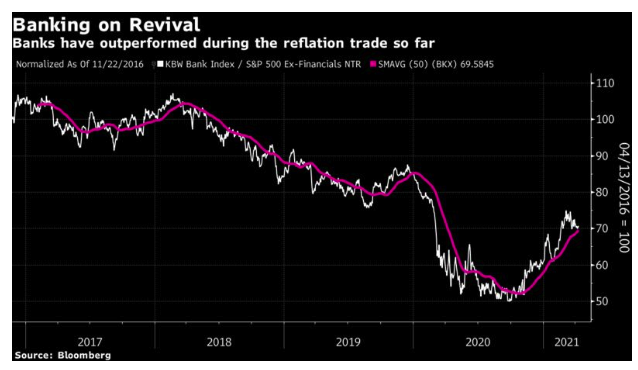

Brace yourself for base effects. The great reflation trade of 2021 faces an important confrontation with hard data over the next few weeks, as companies begin to announce earnings for the first quarter. As usual, the banks will go first, and they will be an interesting test of what is to follow. No sector has benefited more directly from the “reflation trade” of the last few months. Banks borrow short-term and lend over lengthier periods, so are helped by higher yields and a steeper curve (meaning longer-term rates rise by more).

Just as the bond market has been on pause for the last few weeks, so also the banking sector is taking a slight pause. This is how the the S&P 500 financial sector has performed compared to the rest of the index:

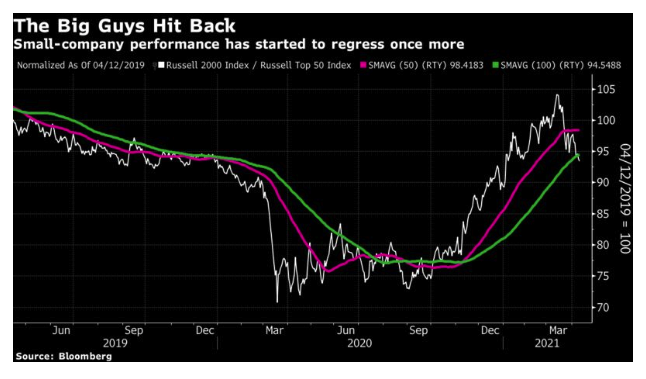

There are other signs that the market is embarking on a repositioning. Smaller companies have far outperformed since encouraging vaccine test results started to appear in November. This is a sign of robust confidence in an economic recovery, which can generally be expected to raise all boats — and thereby help out the smaller craft the most. In the last few weeks, smaller companies have again started to underperform the “mega-caps” that represent the greatest safety, in another sign of what might be nerves about economic reopening:

What is going on? Michael Wilson, U.S. equity strategist at Morgan Stanley, suggests these should be taken as “potential early warning signs that the actual reopening of the economy will be more difficult than many believe.” With markets having discounted the recovery that is now taking shape, they have to execute, “and with that comes execution risk and potential surprises that aren’t priced.” It is probably best to view the entire earnings season as a big exercise in revealing how the recovery is going so far, and what executives expect for the future.

Wilson also suggests that as far as the market is concerned, the recovery has already shifted from early to mid-cycle. This may seem barmy to many, as life drags on much as it has during most of the pandemic. The vaccination program is far from over, and the same is true of the pandemic. But it is the job of markets to discount the future, and the initial recovery phase has already been priced in. That it has happened this quickly is because of the phenomenal pace of this cycle. The downturn was the fastest on record, and much the same can be said of the recovery. That scrambles perceptions, and raises the risk of mistakes.

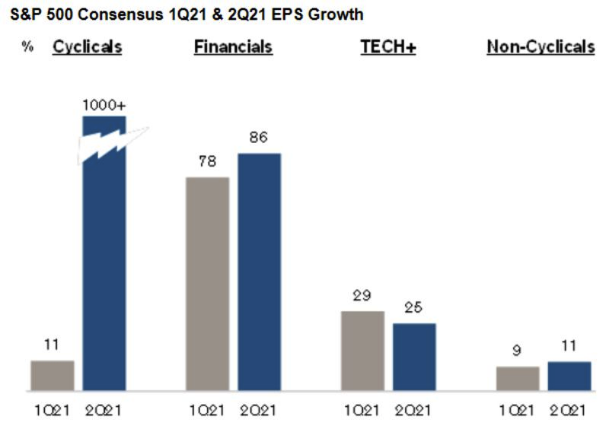

For exhibit a), look at expected year-on-year earnings growth for the first and second quarters, as measured by Jonathan Golub of Credit Suisse Group AG:

The percentage increases on the scale currently being discussed are hard to process and must inevitably come with wide error bars around them. The first quarter will be impressive, and then the second quarter, as shown in the following chart from Morgan Stanley, will be something else:

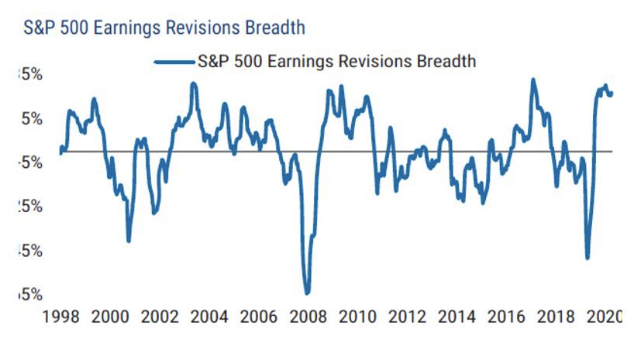

In conditions like this, brokers are struggling to keep up with what is happening on the ground, and will inevitably be more than usually prone to mistakes. The same is true of the corporate investor relations departments who feed them information. According to BofA Securities Inc., brokers revised S&P 500 forecasts upward by the most in any quarter this century. Usually, estimates come down during the quarter as companies try to set a bar for themselves they can beat:

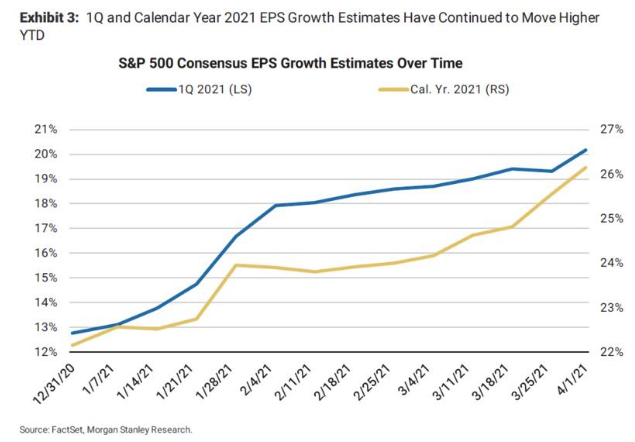

And, as Morgan Stanley shows, that rise in expectations took place more or less constantly throughout the quarter, and affected estimates for the period and the year as a whole:

When we look at which companies have enjoyed the greatest upgrades, the cyclical nature of what is going on becomes clearer. Naturally, energy stocks, beneficiaries of higher oil prices, have seen the strongest upward revisions. They are followed by banks and resources. Meanwhile, though the travel and leisure sector, which has been hurt more by the pandemic than any other, has seen outright downgrades. This is an important clue that there are still doubts over exactly how quickly the economy can exit the pandemic slowdown. The chart comes from Andrew Lapthorne, chief quantitative strategist at Societe Generale SA:

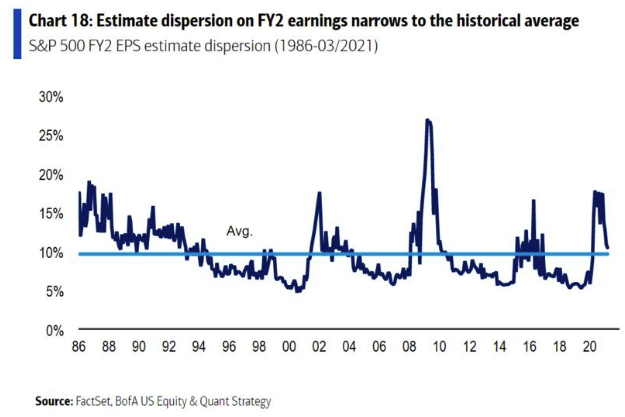

Wall Street seems to think it has more of a handle on next year, with the total range of estimates now narrowing down almost to its typical range. But unpleasant surprises could easily change that:

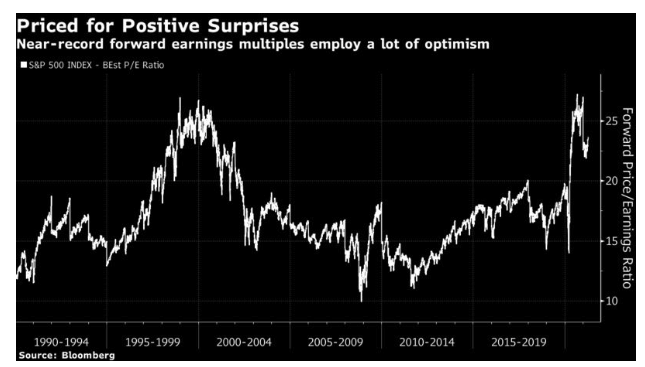

In the near term, stock markets are in the uncomfortable Lewis Carroll state of expecting to be surprised. Looking at multiples of expected earnings for the year as a whole, as reported to Bloomberg, the S&P 500 is expensive as it has ever been, barring the very top of the dot-com boom, and a few weeks at the end of last year. Such high prospective multiples imply either an elevated confidence in continuing growth after this year, or a resolute belief that near-term earnings will be better than the consensus numbers reported to Bloomberg:

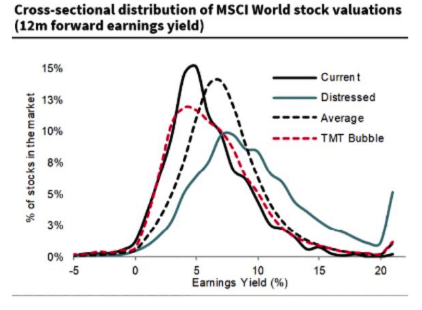

This isn’t only an American phenomenon. Indeed, if we look at the MSCI World index, which includes all the main developed markets, there is an even heavier bias toward extremely expensive companies than there was 21 years ago. According to SocGen, the average stock in the MSCI World is up 20% from the end of 2019, and yet 12-month consensus forward earnings projections are only 3.7% higher. The following chart from SocGen shows the distribution of earnings yields (the inverse of the price-earnings multiple, so that lower yields are more expensive). The current distribution is more skewed toward the most expensive companies than in 2000, and also lacks the usual “tail” of very cheap stocks:

That implies relatively indiscriminate buying, which is what might be expected from people using passive funds to invest stimulus checks in the expectation of a big reflation. Careful judgment of exactly what earnings to expect is close to impossible, and so many judge that it is not worth bothering to try. In this environment, the normal earnings “game” of seeing whether companies can beat the expectations they have set for themselves will be largely inoperative. In the last quarter, stocks that “beat” their expectations tended to fall immediately thereafter, and that might well happen again.

Any negative surprises could have an inflated impact. Most important is inflation. Tuesday’s U.S. data will be influenced by base effects and is deemed certain to show a sharp increase. The latest reading for the annual consumer price index was 1.7%; Bloomberg’s survey of forecasters’ predictions for this month range from 2.3% to 2.7%.

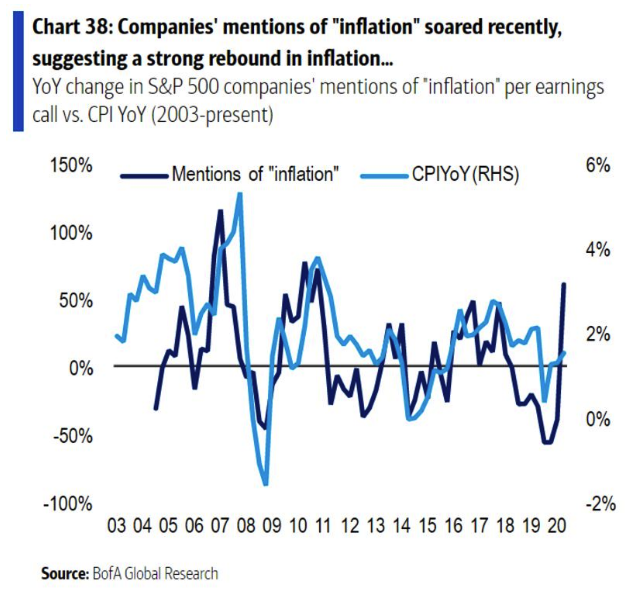

Starting Wednesday, we should also start to get more granular information on how higher costs are affecting companies. A number of industry surveys already show fast rising cost pressures. These would be a natural consequence of supply shortages and bottlenecks in the wake of a big recession, but we need to know how bad they are. Three months ago, mentions of inflation by executives on earnings calls shot up in a way not seen since the oil and commodities price spike that preceded the global financial crisis, as shown in the following chart from Savita Subramanian of BofA. Will the preoccupation with costs continue?

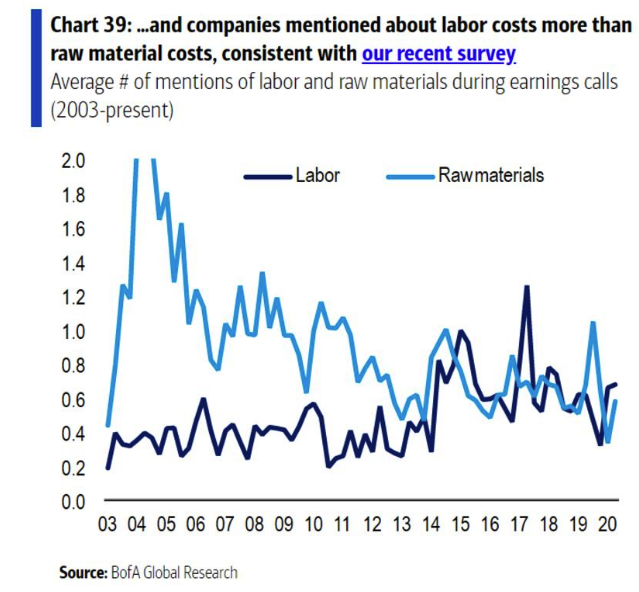

And with the vote over whether an Amazon.com Inc. facility in Alabama should unionize bringing labor costs into a newly sharp focus, it will be interesting to see what weight executives give to them relative to materials costs (which we already know have risen). It looks as though labor costs are already beginning to take over as their prime concern:

There may well be much further for the reflation trade to run. But it has come a long way in a hurry. It isn’t surprising that the market is shifting a little further away from the reflation narrative at this stage in proceedings. The next dose of corporate data could determine whether that trade can pick up again in full force.

Survival Tips

There are times when nothing but a viral clip will do. I recommend watching this, which is the American actor Mike Warburton singing and beatboxing his own cover version of Whole Lotta Love by Led Zeppelin, on Norwegian television. Here is the original, so you get an idea of how good and accurate it is. All in, beatboxing may be the perfect pandemic activity.

Warburton can also be found doing Immigrant Song, which I find even funnier. This is the one that starts with Robert Plant doing a Tarzan-style yodel, as you can see here. Immigrant Song might be my favorite Led Zep song, partly because it's less than four minutes and avoids their tendency toward self-indulgence, and partly because it turns out that the song is all about Iceland, inspired by a visit the band made to the island for a festival. Once I read through the lyrics, I discovered that it was about a rebuke to the island's leadership over the Icelandic financial crisis, 40 years ahead of time:

And now you'd better stop/ And rebuild all your ruins

Because peace and trust will win the day/ In spite of all you're losing.

Warburton also does a very good Jimi Hendrix. Other examples of great beatboxing greatly appreciated.

John Authers is a senior editor for markets. Before Bloomberg, he spent 29 years with the Financial Times, where he was head of the Lex Column and chief markets commentator. He is the author of The Fearful Rise of Markets and other books.