For years, bonds were largely neglected as stocks continued their upward trajectory. From time to time, people have worried about the negative impact that rising inflation and interest rates would have on bond prices. But the slow pace of economic growth and inflation kept those concerns in check.

That changed earlier this year when low unemployment numbers, the rising federal budget deficit and wage growth rekindled fears of inflation and rising interest rates. As the stock market tumbled, bonds, a traditional safe haven in times of stock market mayhem, got caught in the undertow.

Even before the market rout, some vocal soothsayers were wary about the bond market’s prospects for 2018. Hedge fund titan Ray Dalio sounded one of the more alarming warnings when he declared on Bloomberg TV “a 1% rise in bond yields will produce the largest bear market in bonds that we have seen since 1980 to 1981.”

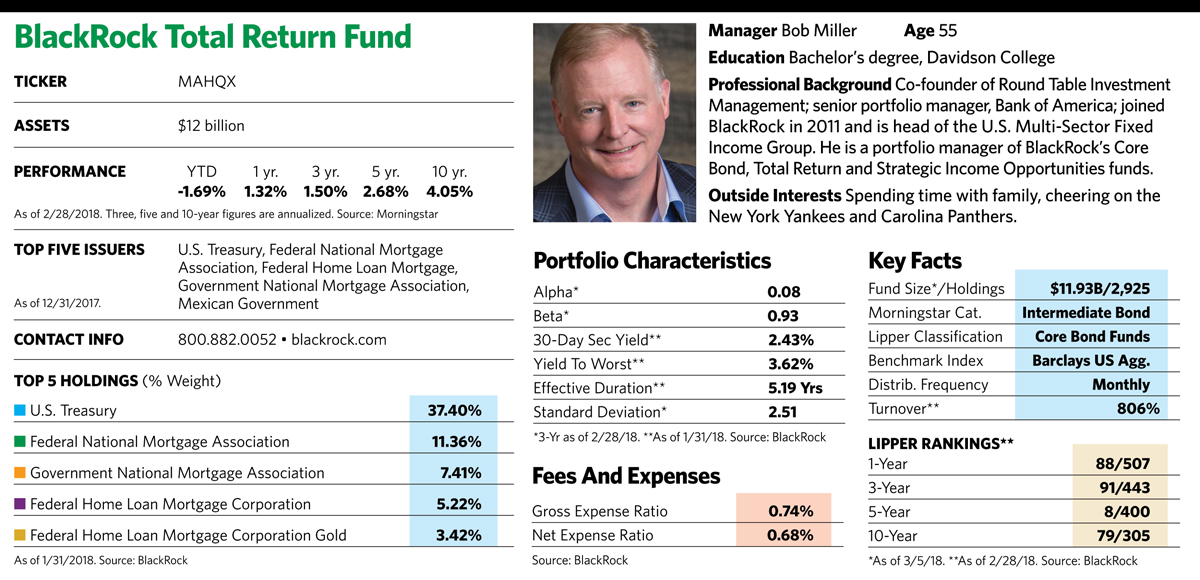

Bob Miller, who manages the $12 billion BlackRock Total Return Fund with fellow bond guru Rick Rieder, also sees a tough road ahead for bonds as the era of ultra-low rates appears to be drawing to a close. But the 55-year-old manager takes a much more measured stance on the eventual fallout than Dalio. The broad bond market, he believes, will likely end the year with total returns that are flat or slightly down. His goal for the fund is adding 100 basis points to 200 basis points of incremental return to the fund’s benchmark, the Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond Index, through active management and risk control measures.

Despite his measured stance on the market, he doesn’t downplay the risks. “I don’t like to make bull or bear market calls,” says Miller, who heads up the U.S. Multisector Fixed Income Group at BlackRock. “But I will say this is one of the trickiest bond markets for investors in a long time.”

Miller, who has managed bond portfolios for over three decades, also navigated some fairly tricky markets at Bank of America for 20 years before he joined BlackRock in 2011. He says today’s scenario reminds him of the late 1990s and early 2000s, when the Federal Reserve kept a lid on interest rates for an extended period of time before finally adjusting them upward. During both periods, the markets experienced unusual volatility before finally settling down.

Playing Defense

Miller emphasizes that in the current environment, when interest rates appear poised to move up, picking the best spots on the yield curve is critical. “The front part of the yield curve is still a strong diversifier for risk assets such as equities,” he says. “You can own bonds that mature in two to five years and still achieve diversification without the duration risk of longer-term bonds.” Since the yield curve has been fairly flat, he adds, shorter-term bonds don’t yield that much less than those with longer maturities. Recently, five-year Treasury note yields were roughly 80% of the yield on 30-year Treasurys. His conviction that the shorter end of the yield curve offers the best value has kept the fund’s duration at 5.39 years, which is lower than that of its index benchmark.

In addition to shortening duration, the fund is also dealing with the uncertain fixed-income environment by remaining flexible and coloring outside the index box when necessary. At the beginning of the year, the fund had a stake of about 6.42% in emerging market bonds, while the index’s stake was 1.83%. Miller thinks there are some “select stories that are attractive in this complicated asset class,” and depends on BlackRock’s deep bench of fixed-income analysts to help uncover them.

There’s also an ample dose of floating-rate securities in the form of non-agency mortgages and collateralized loan obligations, two areas where the benchmark has no presence and demand by investors is strong. Miller and Rieder complement the portfolio with risk control tools that are rarely found in an intermediate-term bond fund, including U.S. interest rate derivatives and put options on the S&P 500. The puts, he says, are useful for cushioning the drop in high-yield bond prices that often occurs when stocks go down.

Risk controls and attention to macroeconomic forces have helped the fund earn a Morningstar “Silver” designation and a four-star rating. The fund underperformed its peers in 2011, the first full year that Miller and Rieder took over as co-managers. But since then it has outperformed its average peer in Morningstar’s intermediate-term bond category every year. Over the last five years, the fund has captured 114% of the upside of its benchmark index but only 89% of its downside.

Battling Headwinds

For Miller and Rieder, playing defense now is critical with the number of headwinds at play. One of those is a decoupling of the traditional seesaw relationship between bonds and stocks. Historically, bond prices have tended to rise when stock prices fall as investors flee the volatility of equities for the safety of the bond market. But over the last few months, that hasn’t always happened. At some points, investors have moved into bonds when the stock market has dropped, which boosts prices. At others, both the stock and bond markets have moved down in tandem.

Miller thinks the image of bonds as safe havens during stock market turmoil has diminished somewhat because investors are becoming increasingly concerned about the growing budget deficit. He questions why there’s been so much fiscal stimulus in the form of tax cuts and spending when the economy has already showed strong signs of upward momentum. “The federal government promoting stimulus at a time when we’ve reached full employment? That hasn’t happened since the mid-1960s,” he says. “That’s a powerful motivator for inflation and interest rates to move modestly higher. I think the political process recently has been unusually shortsighted.”

If the Treasury issues a flood of new bonds to pay for all the tax cuts and spending increases, government buyers may not be eager to absorb all that new supply. “Deficit spending and concerns about the market’s ability to absorb new issuance is spooking the bond market,” he says. “Politicians are underestimating the degree to which the private sector will need to step in to buy government bonds.”

Moving into below-investment-grade bonds is also less appealing as a way to soften the blow of rising interest rates. Under normal market conditions, these securities tend to be less interest-rate sensitive than government or investment-grade securities, making them something of a fixed-income shelter when rates rise. But with more investors tapping the high-yield market in recent years, both prices and yields have become less attractive than they were in the past. “With credit spreads so tight, the potential for high-yield bonds to absorb interest rate increases is minimal,” Miller says.

Inflation’s Up, But Under Control

Yet another problem is investor perception about the threat posed by increasing inflation. Over the last few years, new technology that streamlined the production, marketing and distribution of everything from food and apparel to recreational goods has kept prices low and inflation modest. With greater efficiencies, prices could rise more slowly than they would have in the past—and if wages are kept in check. But over the last year, the dollar’s sliding value against other currencies has added to inflation by making some imports more expensive. And with unemployment at historic lows, the signs of upward pressure in wages are surfacing.

“We’re keeping a close eye on wages growth as a key determinant for predicting the Fed’s movements this year,” Miller says.

There are a few bright spots on the horizon. Despite widespread investor concerns about an overheated economy, any increases in inflation and interest rates are likely to be modest. “By historic standards, interest rates are not high compared to inflation,” he says. “The problem is that people got used to abnormally low interest rates.” Inflation, which has averaged around 1.7% over the last few years, could tick up to 2% or 2.25% over the next year or two, while the rate on the 10-year Treasury could get as high as 3.25% later this year.

The new chairman of the Federal Reserve, Jerome Powell, will obviously have a strong influence on where interest rates go. Miller views him as “a talented person with substantial experience” who is likely to follow in the measured and transparent footsteps of his predecessor, Janet Yellen. Nonetheless, “it’s likely that we’ll see three to four interest rate hikes this year, depending on how quickly the economy seems to be expanding.”