Some notable portfolio managers grab headlines, make frequent appearances on financial-market television shows and, in extreme cases, attain rock star status. That will likely never happen with any of the people calling the shots at Dodge & Cox’s seven mutual funds. Why? Because each product is run by a multi-member investment committee in which everyone has equal say about what securities go into and out of a portfolio.

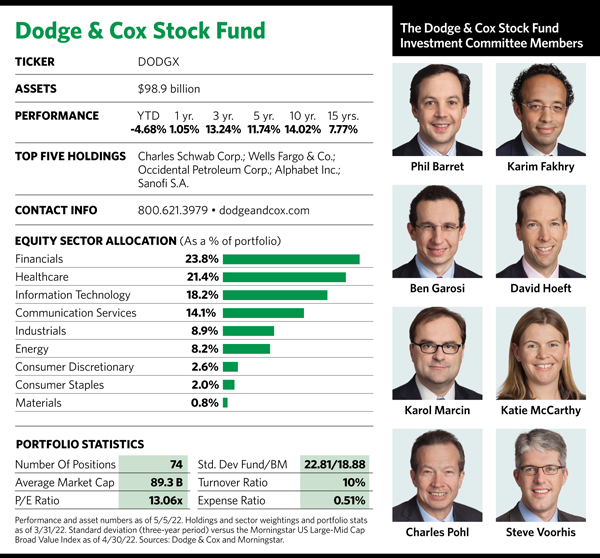

“It really is a team effort; it’s not just a manager backed up by a team,” says Steve Voorhis, research director and one of eight investment committee members on the Dodge & Cox Stock Fund. “Pretty much everything we do on the investment committee is collaborative and team-based.”

Members who achieve investment committee status typically work on two or three of the company’s funds, and most are analysts who cover specific sectors either in the equity or fixed-income spheres. They work with other research analysts at the firm who cover particular sectors; each analyst is paired with a research associate, a setup that Voorhis says enables Dodge & Cox to dig deeper into investable securities.

It’s a system that has produced time-tested, category-beating results for the 57-year-old Stock Fund. The portfolio comprises more than 70 medium- to large-cap stocks that investment committee members chose because they believed they were temporarily undervalued by the stock market but had favorable long-term growth prospects.

The fund has placed in the top quartile of Morningstar’s large-value category during the three-, five-, 10- and 15-year time periods (as of the first quarter). Granted, this year has been rough on the fund, which had lost 4.7% by May 5. That’s a slight underperformance compared to its category, though it’s better than the 6% loss suffered by the Russell 1000 Value Index, which is one of two benchmarks that Dodge & Cox uses as a comparison for the Stock Fund. The other benchmark is the S&P 500, which Voorhis says is more representative of its investment universe. That was down 13% by May 5.

But like any fund manager (or in this case, fund managers) who espouse a long-term investment horizon, the people behind the Dodge & Cox Stock Fund aren’t sweating the recent downdraft. They consider themselves contrarian investors, and sometimes that produces short-term hiccups on the path to longer-term gains.

One example relates to how they played the energy sector when that got slammed during the early days of the pandemic. “Two years ago we significantly added to our energy holdings at a time when energy prices were negative for a few days,” says Phil Barret, a Stock Fund investment committee member. “We thought about the range of outcomes over the next three to five years, and supply and demand in this sector.”

During those dark days for the energy sector, the fund’s managers leaned heavily on the firm’s fixed-income and credit group to gauge the short- and medium-term liquidity and financing capacity of certain companies in that sector. “That work gave us confidence—in that while energy prices were negative, our holdings had the benefit of time and could weather the volatility until prices recovered,” he says.

More recently, the fund in the first quarter added to its position in Meta Platforms, formerly known as Facebook, whose stock got walloped after it reported disappointing earnings in February that blindsided investors. “That position is illustrative of our long-term, bottom-up investment horizon,” Barret explains, adding that price dislocations in quality companies with solid three- to five-year growth prospects present intriguing buying opportunities.

“It enables us in certain circumstances to buy fast-growing franchises that might not be considered a prototypical value stock,” he says.

Value Doesn’t Always Come Cheap

When it comes to stock analysis, affixing valuation can be as much art as it is science.

“There’s no magic in how we look at valuation,” Voorhis says. He notes that he and his colleagues look at the usual metrics including price-to-earnings, price-to-sales, price-to-EBITDA, price-to-cash-flow and the like. But cheap valuation metrics are sort of like empty calories when a company has lousy growth prospects.

“We pay a lot of attention to valuation, but we don’t want a portfolio that’s crowded with those sectors of the economy that will shrink as a percentage of GDP over time,” Voorhis says.

He notes that Dodge & Cox analysts probe deeper to flesh out a fuller picture of valuation beyond typical generally accepted accounting principles, or GAAP. “GAAP accounting is really based on thinking about firms in the physical world and takes into account capex and depreciation, and doesn’t take into account spending on innovation,” Voorhis states. “It’s often important to disaggregate companies and look at different parts of the business that may have different characteristics. You might have one part of the business generating earnings and cash flow, and another part that’s in investment mode and losing money.”

He adds that while not every company in the Stock Fund’s portfolio jumps out as being a value stock in a traditional sense, the fund’s overall valuation discipline comes into play when viewed across the entire portfolio. According to Morningstar, the fund holdings sport lower price-to-earnings, price-to-book and price-to-sales measures than the overall large-value category. Meanwhile, the portfolio registers higher historical earnings, sales and cash-flow growth rates than the category average.

Avoiding Groupthink

Dodge & Cox is part of the asset management industry’s old guard. Formed in 1930 by Van Duyn Dodge and Morrie Cox, the San Francisco-based firm managed nearly $365 billion as of the first quarter. Two-thirds of that was parked at its seven equity and fixed-income mutual funds. The rest resided in separately managed accounts for institutional clients and in UCITS funds for clients outside the U.S.

Barret says he doesn’t know for sure if the team-based approach to fund management has been in place since the start, but it has been that way for as long as anyone at the company can remember. The number of people on a particular fund’s investment committee varies from six to eight members.

“Our view is that there are real benefits to the investment committee,” he says, offering that it leads to thoughtful, independent judgments derived from a collective knowledge base. The Stock Fund’s investment committee typically meets every Tuesday morning, but it can meet more often during times of market turbulence. That said, they say they don’t make knee-jerk investment decisions based on sudden market events.

“Talking to each other usually picks up when things are more volatile and there’s more to discuss when there are current events influencing our portfolio holdings,” Barret says. “But the cadence of our investment meetings hasn’t significantly changed.”

As Voorhis describes it, during those Tuesday meetings an analyst proposes that the fund should buy Company X or add to Company Y. They have a detailed presentation that investment committee members read in advance. The members come in with questions and then discuss and debate an idea. Ultimately, they take a vote and abide by the outcome.

“We’re able to have those discussions in a pretty forthright manner because we’ve known each other for decades, and can go into a committee meeting and completely disagree about something but come out and have lunch together,” Voorhis says.

He notes this is a process they try to refine over time because they’re aware of some of the pitfalls associated with a team-based decision-making process. Barret adds that they’re very conscious of trying to remove behavioral biases from the process.

“There can be pitfalls in investment committees in terms of groupthink and anchoring and cascade effects,” he explains. “And over time we’ve been deliberate in trying to address potential behavioral biases. For the voting, we use a two-stage, blind voting process where people have to think about a problem over a period of days, not minutes. People can adjust their opinions based on new information. Also, we all vote anonymously.”

Bottom-Up

As of the first quarter, the Stock Fund had a roughly 12% stake in non-U.S. equities. Voorhis says the team likes having a small portion devoted to overseas stocks for diversification purposes, but the fund limits that exposure to large, multinational companies with listed American depositary receipts that trade on the New York Stock Exchange.

The firm’s bottom-up research approach means the team focuses more on individual securities than on broad sectors when making investment decisions. “We can form narratives around sectors, though sectors don’t tell you that much,” Barret says. Instead, he adds, the team seeks to evaluate companies by evaluating various factors that can influence performance among players in a specific sector.

He points to four positions in four different industries that were added to the Stock Fund in the first quarter—Gaming & Leisure Properties (a REIT), General Electric, UBS Group and Zimmer Bioment (a medical device maker)—as representative of the firm’s bottom-up approach to identifying value investments.

“Over the past year, a lot of the opportunities we’re finding in new positions have been idiosyncratic in a wider variety of industries that reflect the market reality,” Barret says.

And given how the financial markets have performed so far this year, they’ll likely find many other idiosyncratic investment opportunities.