The technology sector is filled with names such as Apple, Microsoft, Amazon and Facebook that are readily familiar to consumers. Semiconductor companies, though, don’t enjoy those high profiles, perhaps because they do the grunt work behind the scenes making the chips and other components that serve as the nerve centers for a wide array of glitzy devices.

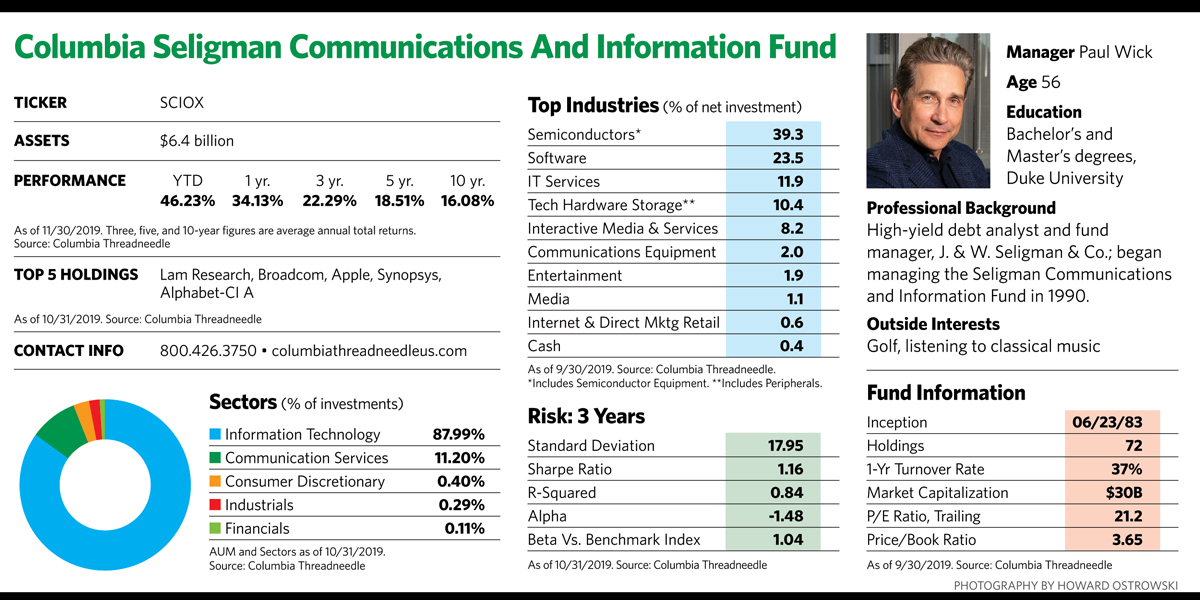

“People think of semiconductors as less exciting companies in a plodding industry,” says Paul Wick, who has managed the Columbia Seligman Communications and Information fund for nearly 30 years. “But there are really a number of exciting stories in the sector.” Since 2012, the fund has allocated between 28.5% and 50% of its assets to semiconductors, according to Morningstar, well above the 11.4% to 15.9% allocation in the S&P North American Technology Sector Index over the same period.

After a disappointing 2018, semiconductor stocks were among the market’s biggest winners in 2019. By mid-November, the SPDR S&P Semiconductor ETF (XSD) had posted a total return, year to date, of 55%, more than double the return of the S&P 500 over the same period. With the tailwind of a significantly higher allocation to semiconductors and semiconductor equipment stocks than most of its tech peers have, Wick’s fund delivered a 45% return over the same period, beating the category competition by about 15 percentage points.

Despite the surge, he doesn’t think semiconductor stocks are in bubble territory. As a group, they still trade at less lofty valuations than broad market indexes, have better growth prospects than most companies and enjoy an increasingly diverse end user base that helps make them more resistant to recession. In the 1990s, personal computers accounted for 55% to 60% of global semiconductor industry revenue. Since then, semiconductors have found their way into everything from health-care devices to television sets and automobiles.

The companies in Wick’s portfolio also have strong intellectual property value and improving profit margins. They are enjoying firmed up prices and demand for their products, demand that had lagged in 2018 and the beginning of 2019. M&A has become more commonplace in the industry, and several of Wick’s portfolio companies have been acquired in the last couple of years. Still, he acknowledges, the sector could be hurt by the continuing threat of a trade war with China and the lingering uncertainty about U.S. semiconductor companies’ sales to Huawei, the Chinese telecom company.

A Different Path

The fund’s strong resolve about semiconductor strength shows its willingness to chart a course different than its peers. Unlike many tech managers, Wick is wary of what he considers extremely high valuations and investment fads, both of which run rampant in the world of technology. He often invests less than most tech fund managers in some of the indexes’ most popular stocks, or doesn’t invest in them at all. His sector weightings can vary a lot from those of the benchmark.

With his focused portfolio of 50 to 65 stocks and his top 10 holdings representing 40% to 50% of assets, his performance skews toward a relatively narrow group. Mega caps with $100 billion or more in market capitalization account for only 29.32% of fund assets, while they represent 66.84% of the index. Small and mid-cap stocks with public values between $2 billion and $30 billion, on the other hand, are heavily overweight in the fund because they tend to be less risky than small caps but have better growth prospects than mega-cap companies. They are also more likely to be acquired, and they can be undervalued because they are less followed by investors and analysts.

While the fund owns a few popular industry titans, including Apple, Alphabet and Microsoft, these don’t occupy nearly as much space as they do in the index. Wick calls Apple, which has been in the fund since 2006, “a great franchise and best-of-breed company that’s been extremely profitable.” He likes its tendency to buy back stock, which helps profitability.

Price Matters

Wick’s investment philosophy and distaste for overpaying for stocks began to take shape in 1987, when he began his career as a high-yield debt analyst at Seligman. He went on to manage the firm’s high-yield debt fund two years later, and then took over its equity technology fund after its manager left in 1989. “No one else wanted the job,” he recalls when asked why he made the transition from bonds to stocks. “It was a small fund and a big research headache.”

Within a few years, of course, the personal computer revolution would move technology stocks from the background to the forefront. Later, the internet revolution, the popularity of cell phones and widespread computerization would change the way people live and alter the investment landscape.

Through all of it, Wick never forgot that financial stability and price matter, even in the fast-paced world of tech stocks. “As a high-yield bond fund manager I had to pay attention to cash flow statements, balance sheets and profitability. That carried over when I went to the equity side,” he says.

Wick’s educational background, which includes liberal arts and graduate business degrees from Duke University, did little to prepare him for the complex world of tech stocks that he’s navigated for nearly three decades. He credits a deep analyst bench with educational and professional technology expertise with helping him separate the companies with the most promising products from those more likely to hit the tech dustbin.

Avoiding Fads

In his search for value, Wick has long avoided faddish, hit-driven businesses that risk uncertain staying power, face lots of competition, suffer low profit margins and experience declining market share. He also watches a stock’s market activity and steers clear of companies with significant insider selling by management, dwindling institutional ownership and high levels of short selling.

He cites online used car retailer Carvana as a hype-driven company that investors are paying way too much for. “Basically, this is a glorified retailer burning over one-half billion a year in cash [and] trading at over three times revenue,” Wick says. “Netflix, Wayfair, Uber are just a few other examples of companies that are burning through cash like crazy. The same holds true for the publicly traded companies that sprang up after the legalization of marijuana and are losing money. Meanwhile, semiconductor companies remain profitable.”

Companies that capture his attention must have strong current or near-term profit margins and cash flow, recurring revenue, differentiated intellectual property and high barriers to entry. Those that are logical takeover targets, as well as those that make value-enhancing acquisitions, also get preference. He is most likely to buy when investor misunderstanding or under-coverage by analysts is making the stocks cheap, as long as analysis reveals that recovery is likely.

The fund’s top two holdings, Lam Research and Broadcom, are sweet spot companies for Wick. Lam, a Fremont, Calif., company founded in 1980, makes advanced microchips. The fund first invested in the company in 2012 after Lam acquired another fund holding, Novellus, in a stock transaction. Since then, the revenues of the enterprise formed from their combination have grown from $2.8 billion to nearly $11 billion. Lam has not made any other acquisitions since then, so that growth has been entirely organic.

The company’s active share buyback program shrank its share count by 13% over the last year, a move that has helped its earnings per share—the figure was at $14.55 for the fiscal year ending June 2019, down from the same period in 2018, but Wick thinks earnings could increase to $18 or $20 a share in 2020.

Broadcom, a company with a history of prudent acquisitions, is a longtime top 10 holding in the fund and has branched well beyond semiconductors. A little over a year ago, the company announced it would acquire CA (the old Computer Associates), the last major public mainframe software company. While many investors were skeptical of Broadcom’s foray into enterprise software, CA has added significantly to earnings. In November, Broadcom acquired the enterprise security software division of Symantec for $10.7 billion.

“Investors have become wary of Broadcom’s acquisitiveness, which brings some uncertainty and has pressured the stock,” observes Wick. “But in prior transactions, Broadcom’s management has significantly reduced costs in the acquired company and successfully integrated them into Broadcom’s portfolio of businesses. The company has the best management team and the highest profit margins in the global semiconductor industry.”