KEY TAKEAWAYS

· The Chinese yuan was added to the IMF’s SDR basket on October 1, 2016.

· A currency’s inclusion in the SDR basket does not make it a “reserve currency;” that label is conferred by the market itself based on the currency’s use in global trade.

· Although the Chinese government has made broader use of the yuan in global transactions a priority, in practice the yuan has gained very little in terms of global acceptance.

The Chinese yuan was added to the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) basket of currencies, called Special Drawing Rights (SDR), on October 1, 2016. The Chinese government has been very open in its desire to have the yuan viewed as a global currency. The inclusion of the yuan in the SDR is largely a symbolic move in this direction. However, being part of the SDR does not make the yuan a reserve currency. For the yuan to be a reserve currency, more trade would need to be conducted in it, and it would need to be used regularly in international finance. Despite the desire to have the yuan become more accepted globally, the amount of trade conducted in the currency has grown immaterially over the past few years.

WHAT IS AN SDR?

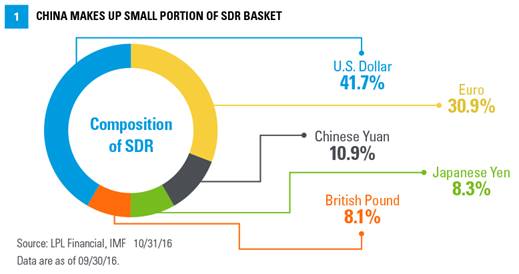

The IMF created SDRs to be used as a supplement to a country’s official reserve assets. Therefore, the SDR can only be held or used by IMF member countries, the IMF itself, and a handful of agencies like the European Central Bank or regional development banks. Furthermore, SDRs can only be exchanged for certain currencies. As a result, the SDR is only of limited use to central banks. Even then, the total issuance of SDRs ($318 billion) is a fraction of total central bank holdings ($17.8 trillion); less than 2% of global central bank assets are represented by SDRs. The weighting of the SDRs is fixed for five years and will be re-evaluated in 2021 [Figure 1]. SDRs do not trade on any exchange; trades are either conducted voluntarily between member countries, or the IMF may facilitate a transaction if necessary, though this rarely happens. Global investment banks do not generally track SDRs, nor convert currencies into SDRs, as they play no real role in global finance.

CURRENCY RESERVES OR RESERVE CURRENCY

SDRs represent a form of currency reserves. This is very different from a reserve currency. The U.S. dollar is the world’s primary reserve currency. Reserve status is not a designation conveyed by the IMF or any other organization. Reserve currencies are determined by their use in global trade transactions, particularly in transactions that do not involve the country of the reserve currency. The fact that when a Japanese company buys oil from a Brazilian one, the transaction is still performed using dollars is the most direct evidence that the U.S. dollar is the leading reserve currency. A country’s currency earns reserve status as the result of building trust within the global community, evidenced by a country’s currency having deep and liquid foreign exchange, bond, and derivative markets; as well as widespread acceptance as payment for international transactions. In addition, the country’s political, economic, and financial structures need to be seen as secure.

What has the Chinese government done to promote the yuan? Perhaps the most obvious measure has been its lobbying to get the yuan included in the SDR basket. While these efforts were successful in getting the yuan in the SDR basket, they have largely been unsuccessful in gaining the yuan broader acceptance. Other measures include the April 2016 creation of the Shanghai Gold Exchange. China is both the biggest producer of gold (that’s right, it’s not South Africa) and consumer of gold. As a result, the Chinese government created a mechanism to trade gold in China, transacted in yuan. Last week, the Dubai Gold and Commodities Exchange (DGCX) announced it will list Shanghai gold futures, the first time that a yuan-based gold product will be traded outside of China.

YUAN ACCEPTANCE

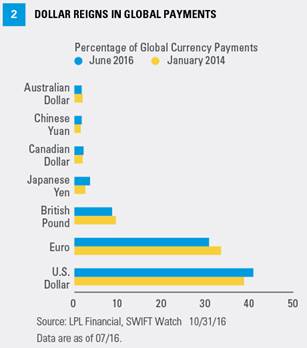

Although the yuan’s inclusion in the SDR represents a public relations victory for the Chinese government, the yuan has struggled for real acceptance as a global currency. The level of acceptance of the yuan can be measured many ways, though they all tell the same basic story. One way is to examine how various currencies are actually being used in global trade [Figure 2]. This shows that despite the inclusion of the yuan in the SDR basket and other measures by the Chinese government to promote its use, the world has been slow to adopt the yuan as a unit of exchange.

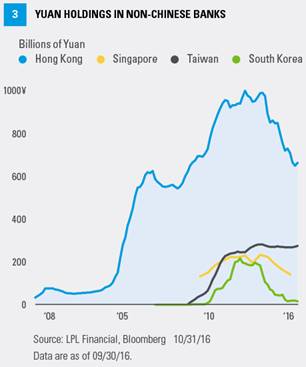

Another measure of a currency’s acceptance is the extent to which it is held outside of its home country. Being willing to hold a currency in a country in which it cannot be spent is perhaps the ultimate vote of confidence in that currency’s ability to hold its value. Indeed, holdings of the yuan increased significantly earlier this decade, mostly in other Asian countries, though this trend has reversed more recently [Figure 3].

Why have global participants been so leery to hold the yuan despite the vote of confidence from the IMF? The reasons are interrelated and pertain to a lack of trust in the Chinese government. One of the biggest fears is the continued devaluation of the yuan against other major currencies. A major devaluation would be in complete opposition to the policy of encouraging use of the yuan as a global currency. Indeed, the Chinese government has been struggling to maintain the value of the yuan; it has declined 5.8% this year against the U.S. dollar after years of almost no movement. However, as both people in mainland China and outside of it question the government’s ability and willingness to support the yuan, fewer people outside the country will be willing to hold it. A currency that no one wants to hold for an extended period will have little use in global trade.

CONCLUSION

The Chinese yuan’s inclusion in the IMF’s SDR program made big headlines when it was announced in November 2015, and this year, when the inclusion was formalized on October 1, 2016. Though there may be very long-term implications for this action, at this point it is almost entirely symbolic and poses no threat to the dollar. In fact, the dollar’s role as the world’s reserve currency has actually strengthened over the last few years. Weakness in the yuan and underlying concerns regarding the Chinese economy mean that the yuan’s ability to challenge the U.S. dollar as the global reserve currency, if even possible, is a long way from being a reality.

John J. Canally Jr., CFA, is the chief economic strategist at LPL Financial.