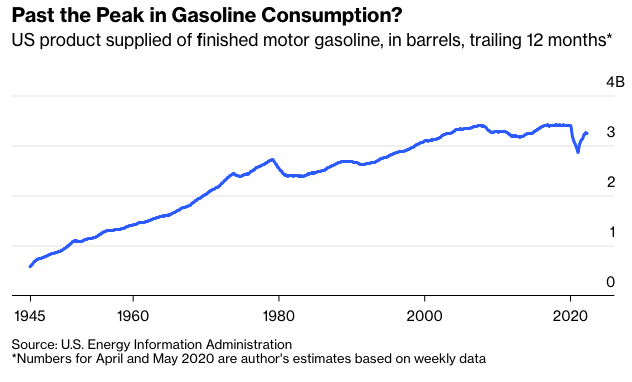

Gasoline consumption in the US probably peaked in the years before the pandemic. It’s currently running about 5% below 2016-2019 levels, and with remote work seemingly here to stay, electric-vehicle market share rising rapidly and population growth awfully close to zero — along with shorter-term pressures such as record-high gas prices and a possible recession — it’s easier to envision more declines than a big rebound.

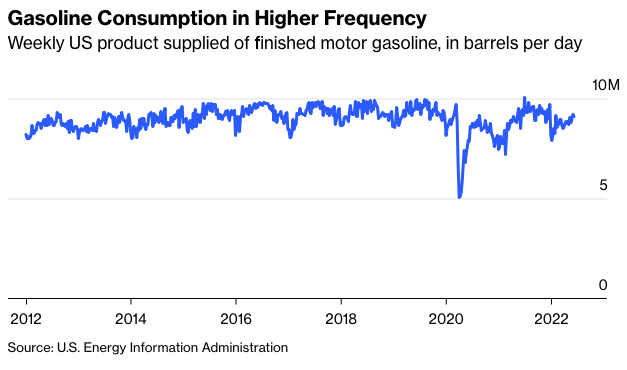

Here’s weekly gasoline consumption over the past decade, to give a better view of recent dynamics.

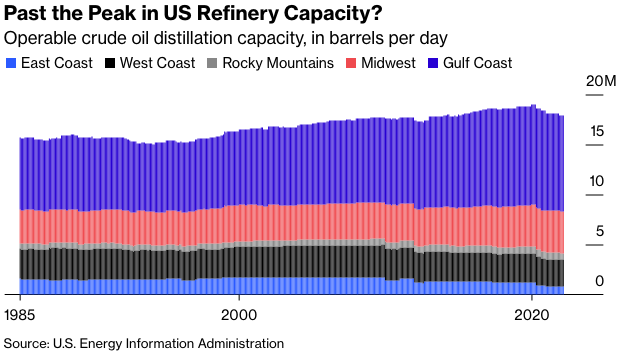

With that context, the fact that refinery capacity in the US also appears to have peaked just before the pandemic does not seem particularly alarming. Three barrels of oil makes roughly two of gasoline, so current refinery capacity of 17.9 million barrels a day of oil equates to about 12 million barrels a day of gas, or three million more than current consumption. The US still has more crude oil distillation capacity than it did in 2007, when gasoline consumption was higher than it is now.

As the chart indicates, though, there have some been shifts in where that refinery capacity is located. East Coast refineries now have less than half the capacity that they did in 2007, while on the West Coast capacity is down 17%. Capacity increases along the Gulf Coast and in the Midwest (which on the petroleum-industry map includes Oklahoma) have more than made up for those declines, but much more of that refinery output goes to exports than did 15 years ago. Throw in the disruptions to oil and petroleum-product markets caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, plus a few other things (my Bloomberg Opinion colleague Javier Blas has an excellent explanation here), and refinery capacity constraints have — via increases in the charmingly named “crack spread” between crude oil and gasoline prices — become the biggest driver of rising prices at the pump.

With that I have pretty much exhausted my limited knowledge of the refining industry, and I don’t have any brilliant ideas for quickly shrinking the crack spread. But I did think it might be helpful to point out that stuff like this happens in declining industries. That is, you might think that reduced demand for a product, and the prospect of more declines in the future, would put downward pressure on prices. And sure, over the long run it often does. Along the way, though, reduced incentives to invest in production capacity and other factors can lead to some interesting dynamics.

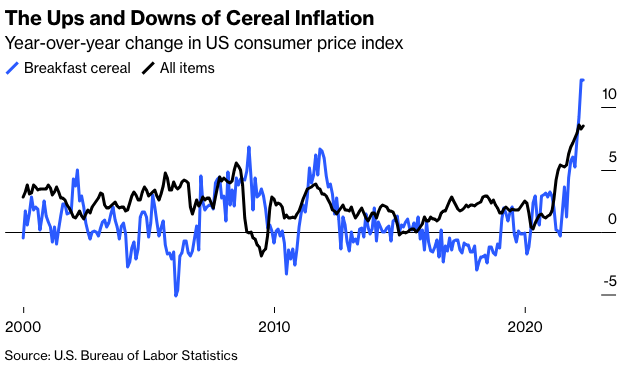

Consider another product that’s in the news this week: breakfast cereal. Sales had been falling steadily before the pandemic, and industry icon Kellogg Co. just announced that it’s spinning off its cereal business to focus on snack products with better growth potential. Measured over decades, cereal prices have been rising more slowly than those of consumer products in general — just what you’d expect given the weak demand. But a pandemic boom in cereal purchases has, along with supply-chain disruptions in an industry that hasn’t had much incentive to invest in expanding capacity, led to sharp price increases.

The consequences haven’t been limited to higher prices. From December 2020 to March 2021 the nation had to do without Grape Nuts, after Post Holdings Inc. shut down the only facility that produces the gritty-yet-in-some-quarters-beloved cereal because so many workers were out with Covid-19.

Fossil fuels are more fungible than breakfast cereals, so precisely that kind of debacle is unlikely. But fossil fuels are also a lot more important to the economy than breakfast cereals, so even temporary price increases really sting. Shutting down production capacity too fast or in the wrong places is one path to price hikes amid declining demand. Another is having to maintain distribution networks even as the amount of product flowing through them shrinks. In California, which is both especially dependent on natural gas for home heating and cooking and especially committed to getting gas users to switch over to electricity, current rules for setting gas rates will translate into much higher bills for those who are late to making the switch — which will likely be lower-income households.

Those rules can be changed, and as detailed in a recent Utility Dive story, California officials are already working on ways to manage the transition. The transition away from gasoline and diesel is clearly going to take a lot of managing, too. The rapid decline of coal-fired electricity generation over the past 15 years in the US has probably given a misleading impression of how easy it is to make such a switch. In coal’s case, most of the immediate burden was taken over by another fossil fuel, natural gas, that had suddenly become abundantly available thanks to the fracking boom. Given how unexpected that boom was, I’m not going to say that something like it will never happen again. But it does seem unwise to count on it.

My point here isn’t that we should stick with fossil fuels. Beyond the obvious need to slow and eventually halt global warming, there are lots of other reasons to look forward to the prospect of an economy fueled by abundant clean energy rather than finite dirty resources. But as we make the transition it’s important to remember that reducing our consumption of something doesn’t equate to ending our dependence on it, and that declining demand doesn’t always equate to declining prices.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. A former editorial director of Harvard Business Review, he has written for Time, Fortune and American Banker. He is author of The Myth of the Rational Market.