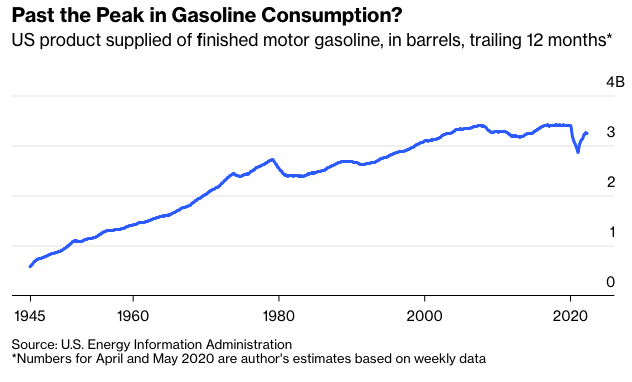

Gasoline consumption in the US probably peaked in the years before the pandemic. It’s currently running about 5% below 2016-2019 levels, and with remote work seemingly here to stay, electric-vehicle market share rising rapidly and population growth awfully close to zero — along with shorter-term pressures such as record-high gas prices and a possible recession — it’s easier to envision more declines than a big rebound.

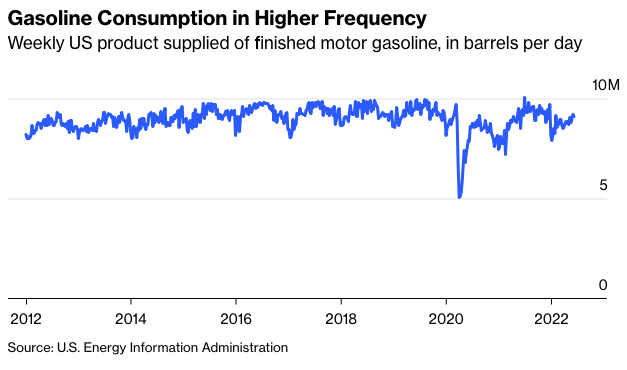

Here’s weekly gasoline consumption over the past decade, to give a better view of recent dynamics.

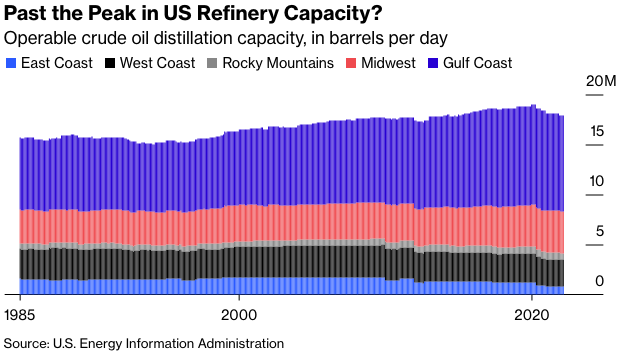

With that context, the fact that refinery capacity in the US also appears to have peaked just before the pandemic does not seem particularly alarming. Three barrels of oil makes roughly two of gasoline, so current refinery capacity of 17.9 million barrels a day of oil equates to about 12 million barrels a day of gas, or three million more than current consumption. The US still has more crude oil distillation capacity than it did in 2007, when gasoline consumption was higher than it is now.

As the chart indicates, though, there have some been shifts in where that refinery capacity is located. East Coast refineries now have less than half the capacity that they did in 2007, while on the West Coast capacity is down 17%. Capacity increases along the Gulf Coast and in the Midwest (which on the petroleum-industry map includes Oklahoma) have more than made up for those declines, but much more of that refinery output goes to exports than did 15 years ago. Throw in the disruptions to oil and petroleum-product markets caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, plus a few other things (my Bloomberg Opinion colleague Javier Blas has an excellent explanation here), and refinery capacity constraints have — via increases in the charmingly named “crack spread” between crude oil and gasoline prices — become the biggest driver of rising prices at the pump.

With that I have pretty much exhausted my limited knowledge of the refining industry, and I don’t have any brilliant ideas for quickly shrinking the crack spread. But I did think it might be helpful to point out that stuff like this happens in declining industries. That is, you might think that reduced demand for a product, and the prospect of more declines in the future, would put downward pressure on prices. And sure, over the long run it often does. Along the way, though, reduced incentives to invest in production capacity and other factors can lead to some interesting dynamics.

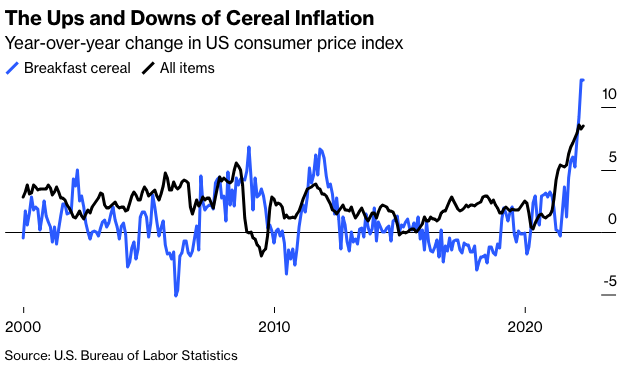

Consider another product that’s in the news this week: breakfast cereal. Sales had been falling steadily before the pandemic, and industry icon Kellogg Co. just announced that it’s spinning off its cereal business to focus on snack products with better growth potential. Measured over decades, cereal prices have been rising more slowly than those of consumer products in general — just what you’d expect given the weak demand. But a pandemic boom in cereal purchases has, along with supply-chain disruptions in an industry that hasn’t had much incentive to invest in expanding capacity, led to sharp price increases.