Key Takeaways

• While the Fed raised its policy rate last week, the more important meeting outcome was the Fed’s guidance on future policy.

• Overall, the Fed’s dots and Powell’s comments point toward a gradual but slowing pace of rate hikes as monetary policy moves closer to a neutral stance.

• However, the disconnect between the market’s and the Fed’s projections for interest rates is growing.

The Federal Reserve (Fed) wrapped up its most recent monetary policy meeting on Wednesday, September 26. While the Fed raised its policy rate, as expected, the more important outcome was the Fed’s guidance on future policy through its statement, a new set of forecasts, and Fed Chair Jay Powell’s press conference after the meeting’s conclusion. The Fed walked a fine line between minimizing the possibility of a harmful pickup in inflation while emphasizing the strength of economic growth and the labor market. However, the market’s response shows the disconnect between the Fed’s and the market’s expectation for future policy is growing.

The Dots

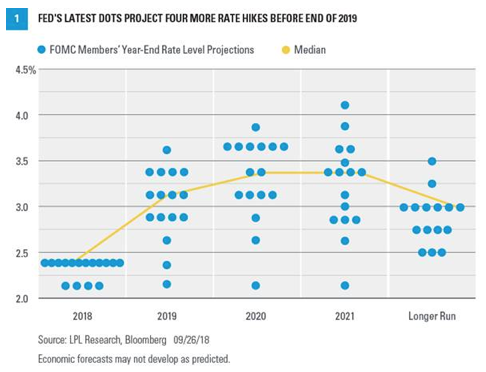

At every second meeting, along with its policy decision and statement, the Fed provides economic and policy projections based on the individual projections of the 12 regional Fed presidents and the 7 members of the Fed’s Board of Governors (with some seats often unfilled due to transitions). Fed members update their interest rate projections in the Fed’s well-known “dot plot,” with each estimate represented by an unlabeled dot. The Fed’s new dots show policymakers project one more rate hike this year (to a fed funds target range of 2.25–2.5 percent), along with three rate hikes next year (to a range of 3–3.25 percent) [Figure 1].

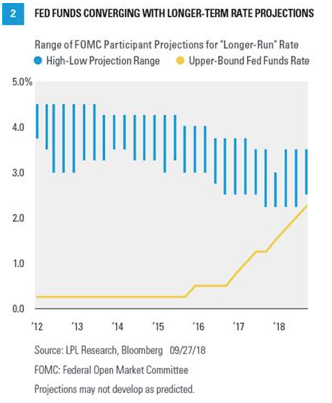

While Powell stated several times in Wednesday’s press conference that the Fed will move forward with gradual rate hikes, the median dot of each forecast implies that policymakers expect the pace of hikes to start slowing next year. The dots show that members expect the fed funds rate range to peak at 3.25–3.5 percent at the end of 2020 before declining to a “longer-term” rate of 3 percent. This longer-term projection is the best gauge of the “neutral rate”—or the point where monetary policy is neither stimulative nor restrictive. The neutral rate is a practical idea rather than a known macroeconomic variable, and it takes a pragmatic policy approach to move toward the neutral rate while avoiding the risks of overtightening or leaving policy too loose. Although the median estimate for the longer-term rate is 3 percent, the dots project a longer-term rate anywhere from 2.5–3.5 percent [Figure 2]. The takeaway here is that although the longer-term projection is a helpful indicator, there is still a degree of uncertainty in determining the neutral rate; and ultimately, the incoming economic data will continue to determine the policy path that provides that best balance of the Fed’s dual mandate of price stability and maximum sustainable employment.

What’s The Story Behind These Forecasts?

When deciphering the Fed’s forecasts for economic variables, we think it can often be helpful to look at the story that these forecasts tell collectively. Here’s a look at the current overall picture based on the updated forecasts:

Working from median projections, the Fed expects the economy can grow at 2 percent in the long run. Right now, with the help of fiscal stimulus, it’s growing above that rate. The Fed expects growth will end up at around 3 percent in 2018, then slow down to a still above-trend rate of 2.5 percent in 2019, and then will come back in line with longer-term expectations in 2020. To help control the prospects of inflation that can come with above-trend growth, the Fed believes it will have to gradually raise rates, but doesn’t need to be aggressive. Through the end of 2019, the Fed expects it will raise rates at just about every other meeting to keep inflation under control, and then can slow down from there. If the Fed does that, it believes inflation will stay near the stated target of 2 percent despite the above-trend growth while causing minimum disruption to the economy. Although the Fed is removing added support to the economy, which can be perceived as putting on the brakes, it’s really just trying to get to the point where it’s letting the economy stand on its own two feet.

What The Market Is Saying

That’s a good story, and is largely in line with market expectations, except for the rate hike projections that go with it. The median consensus estimates for growth and inflation from Bloomberg-surveyed economists are nearly identical to the Fed’s outlook. However, fed fund futures’ rate path expectations are considerably lower than the Fed’s. The Fed sees five additional rate hikes by the end of 2020, while the market projects two.

What might account for this difference? Markets may be looking at a pattern of stubbornly low inflation and a Fed that has often had to go slower than expected. The Fed, on the other hand, may want to account for the possibility that growth and inflation could be higher than expected, which would require a more aggressive but still gradual path for rate hikes. Powell did note in his press conference that the impact of fiscal stimulus is still unknown and it’s possible it will be larger than expected. While inflation has remained well contained, possible pressure from wages, trade, oil prices, and potentially stronger economic growth may make the Fed mildly biased toward controlling for inflation risk. The Fed has been generally on target with its rate path forecasts over the last two years, and with maximum sustainable employment clearly in hand, we would be biased toward the Fed’s view over the market’s if the consensus economic outlook comes to pass.

No Longer ‘Accommodative’

The Fed also removed the word “accommodative” from its description of monetary policy in Wednesday’s statement. While we expected the Fed to make this change in an upcoming policy meeting, we didn’t think it would come as soon as last week’s meeting. Because of this, we interpret the removal of “accommodative” as a nod to the Fed’s positive outlook on U.S. economic growth. If the Fed waited too long to change the language, markets may have misconstrued the delay as an implicit message from the Fed that the economic expansion isn’t as healthy as policymakers expected.

Powell noted in his press conference that this change doesn’t signal a shift in the path of monetary policy, but rather reflects that policy is moving in line with the Fed’s expectations. If anything, the removal of the language has a dovish tilt, as it indicates that we are approaching the range of the neutral rate.

The change was unremarkable for markets, the reaction the Fed was likely aiming for. Markets were likely more focused on the dot plot, which—despite the gradual approach—remains markedly more aggressive than fed fund futures’ implied expectations. The Fed will continue to evaluate upside and downside risks based on incoming data, but right now, it doesn’t see any reason to change its policy approach.

Global Considerations

The Fed’s plans for monetary policy also have come under scrutiny given slower global growth outside the United States and continuing trade tensions. While Powell said the Fed hasn’t seen any significant evidence of tariffs at an “aggregate level,” he did note that the Fed has observed growing labor shortages, supply chain constraints, and added pressure on wages and input costs—all likely influenced by tariffs. Powell also noted the Fed is concerned with the intangible cooling effects, specifically from loss of business confidence, financial market reactions, and the uncertainty of significant escalation from current conditions. But the minimal impact seen to date on the overall economy is still the dominant point, likely due to much more significant offsets from fiscal policy. We side with the Fed here—we believe that the $350 billion tailwind from fiscal stimulus will continue to overpower headwinds from trade. However, the U.S.-China trade situation can escalate quickly, and with midterm elections coming up, we don’t expect an agreement any time soon.

Powell also touched on the Fed’s consideration of recent emerging market (EM) concerns in his comments. He noted that concerns with EM economies, or the global economy in general, are considered in light of their impact on the U.S. economy. Of course, the Fed has a domestic mandate, but we consider global stability the Fed’s unofficial third mandate given the interconnected nature of international economies. The Fed’s tightening path may put further pressure on EM economies, as these countries owe about $4.5 trillion in U.S. dollar-denominated debt, and a rising dollar makes it increasingly difficult for these economies to service that debt.

Conclusion

Overall, the Fed’s dots and Powell’s comments point towards a gradual, but slowing pace of rate hikes as monetary policy moves closer to a neutral stance. According to the Fed’s projections, policy is about four rate hikes away from a neutral rate. However, we think the Fed has several factors to consider when deciding on future monetary policy, and any change in these crosswinds could make it more difficult for the Fed to continue its pace of tightening.

Nevertheless, we remain confident that Powell’s pragmatic approach to evaluating these crosswinds will limit the Fed’s chances of making a policy mistake.

John Lynch is chief investment strategist for LPL Financial.