Many financial professionals still recite a pat response when clients ask about socially responsible investments: beware, they will likely underperform the broad market.

A decade ago, that answer was pretty broad-strokes accurate. Today, that same answer is pretty uninformed. Several studies, published years ago, showed that so-called “sin” stocks, such as alcohol, tobacco and gaming, outperformed. For example, in their 2007 Journal of Financial Economics paper, “The Price of Sin: The Effects of Social Norms on Markets,” Hong and Kaperczyk found sin stocks returned around 3% more per year than comparable stocks (Source: Hong and Kacperczyk , “The Price of Sin: The Effects of Social Norms on Markets,” The Journal of Financial Economics, 2007).

Since most socially responsible investing at the time bluntly excluded these stocks, they could be expected to underperform.

Interestingly, one might argue that this was not a negative finding for socially responsible investors, who at the time were largely comprised of foundations and endowments. After all, the point wasn’t to earn a higher rate of return, it was to avoid supporting undesirable activities, arguably even to punish these enterprises. And by appearances, it worked.

A key principle of investing is that as the price of a stock goes down, the expected return goes up. This is governed by a simple equation known as the “dividend discount model.” Simply put, the stock price is equal to the future dividends (or cash flows) it pays, divided by the required rate of return. (A growth rate is also subtracted from return.)

Stock price = Dividends / Expected return

The return the investor expects to earn is, in fact, the equity cost of capital for that stock. By pushing the prices of these stocks down, institutional investors drove their expected return up. The expected return to investors is the cost those firms have to pay to access capital from the market. Mission accomplished.

So, what has changed today? Enter environmental, social and governance (ESG) investing. A variety of themes can reside under these three buckets, much broader and far-reaching than the original socially responsible investing premise. Environmental investments, for example, may look to underweight or eliminate polluting companies or high carbon emitters, while socially directed investments might rank firms on working conditions and employee relations or human rights records. Governance considers issues such as board diversity, corruption and accounting aggressiveness.

For many, supporting companies that are working toward a better-shared future is reason enough to invest in ESG. Indeed, how much money can we all make in the long run if we let the world go to pot? As Mark Carney, a former governor of the Bank of England and strong ESG proponent noted recently on Twitter, “We’ve been trading off the planet against profit for too long. This has depleted our natural capital, had devastating effects on earth’s biodiversity and is causing unprecedented changes to our climate.”

Universal owners, large institutions who essentially own everything, have long understood that systemic problems are investment problems. But what about individual investor returns?

While the themes may differ from socially responsible investing, in one sense, the same story still applies. Just as investors avoid tobacco and drive its price down and return up, so too they will drive up the price of renewable energy firms or companies that invest in their workers, and expected returns for these “good” companies will decrease, right?

True, but ESG comes with something else: an alpha thesis. There are good reasons to believe that investor preferences for these stocks will be validated by better actual corporate performance, leading to higher cash flows. Thus, the numerator in the dividend discount model goes up, offsetting the denominator increase coming from increased interest.

Why might ESG-aware firms outperform? There are a variety of specific reasons, from avoidance of fines and responsiveness to physical threats and cost efficiencies, but they largely center around the expectation of a landscape that is fundamentally transitioning. This transition is coming about both because climate change has the potential to irreversibly alter productive operations as we know them and because clients, regulators and business partners are increasingly demanding that the private sector incorporate ESG concerns into their businesses. As with any paradigm shift, there will be winners and losers, and investors are looking at ways to make sure they are investing in the winners.

Thus, for many, ESG investing is not just about incorporating their values in their investments, but also about adding value—reducing risk, adding return or both.

The impact of climate change in particular is a risk that many in our industry are sounding alarms about. BlackRock CEO Larry Fink took an unmistakable stance in his 2021 letter to CEOs: “There is no company whose business model won’t be profoundly affected by the transition to a net zero economy – one that emits no more carbon dioxide than it removes from the atmosphere by 2050, the scientifically-established threshold necessary to keep global warming well below 2ºC … companies that are not quickly preparing themselves will see their businesses and valuations suffer, as these same stakeholders lose confidence that those companies can adapt their business models to the dramatic changes that are coming.”

The world’s largest money manager is not alone in this thinking. European policymakers have arguably led the march to incorporate rules around climate, but the United States is quickly following suit. The Biden administration has made climate risk and ESG top priorities, not just in social arenas, but in financial ones. For example, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has pledged to put together a team to look at financial system risks arising from climate change, which she refers to as an “existential threat.”

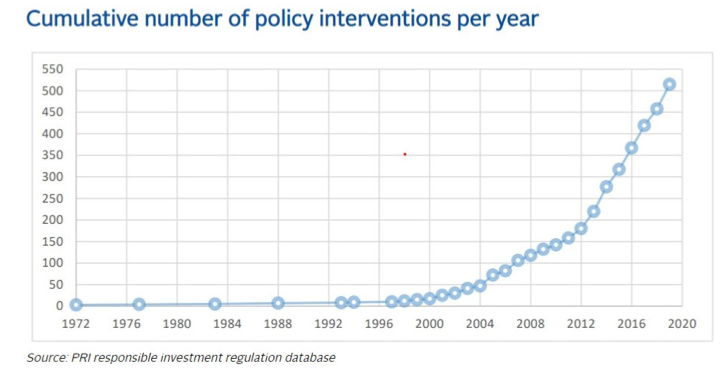

The Principles for Responsible Investment, an international network of investors working to understand and incorporate ESG, tracks regulations around long-term value drivers such as ESG. Its 2019 update showcases the tremendous increase in these types of policy interventions.

Investors seem to be listening. Interest in ESG investing has increased dramatically over the last several years, and it’s not just the purview of pensions and endowments anymore.

Sustainable funds pulled in $51.1 billion in net flows in 2020, more than doubling the record set the year before, according to Morningstar. Fund flows into these products accounted for nearly one fourth of overall flows into funds in the United States (Source: Morningstar “Sustainable Funds U.S. Landscape Report,” 2020).

So, what is the net takeaway on performance expectations for socially responsible investments, given that this umbrella now includes and is increasingly focused on ESG? Thousands of studies have tried to answer this question. But the truth is that, for the individual advisor or investor putting together a portfolio, there is no correct sweeping answer, particularly since these investments can vary dramatically. More sophisticated approaches—oftentimes not just excluding unwanted companies, but more carefully integrating ESG themes to under and overweight within sectors—can minimize tracking error, making it possible to invest in ESG without betting the farm. On the other hand, thematic investments can feature concentrated bets on specific aspects of ESG that an investor may believe is poised for outperformance, say water scarcity or board diversity.

The track record on these newer investments is just not long enough to be able to judge empirically. Early evidence is positive, with ESG funds performing particularly well in 2020 and demonstrating risk-reduction potential. Deutsche conducted a meta study, published in 2015, combining the results of about 2,200 studies on ESG and corporate financial performance going back to the 1970s. About 90% showed non-negative relationships, with the majority finding a positive relationship, though portfolio studies were less positive, suggesting that investors in these companies via vehicles like mutual funds had not necessarily earned this outperformance (Source: Gunnar Friede et al. “ESG and financial performance: Aggregated evidence from more than 2,000 empirical studies,” Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment, October 2015, Volume 5, Number 4, pp.210-33, Deutsche Asset & Wealth Management Investment). More recently the NYU Stern Center for Sustainable Business and Rockefeller Asset Management announced findings from a meta-study focused on 1000 papers on ESG done in the last five years. Among the findings was that sustainability initiatives appear to lead to improved risk management and greater innovation (Source: Whelan, Tensie, Ulrich Atz, Tracy Van Holt and Casey Clark. “ESG and Financial Performance: Uncovering the Relationship by Aggregating Evidence from 1000 Plus Studies Published between 2015 -2020.” Rockefeller Asset Management and NYU Stern Center for Sustainable Business.).

Governance themes in particular seem correlated with quality measurements, a style factor anomaly that has long been associated with positive return and reduced risk. In 2019, MSCI published its own meta study and found “significant evidence that the application of MSCI ESG Ratings may have helped reduce systematic and stock-specific tail risks in investment portfolios.” (Source: Giese, Guido and Linda-Elling Lee, “Weighing The Evidence: ESG and Equity Returns,” MSCI, April 2019.) MSCI has also begun looking at ESG as its own factor, and early evidence is that its efficacy in explaining stock-specific risk is increasing, possibly due to increased firm investment in sustainability-related measures (Source: Factoring in ESG,” MSCI, Feb. 26, 2021).

Is recent outperformance the reason money is piling into these investments? Maybe. There’s a shorter-term aspect to the alpha thesis that might also be driving such interest, namely, the desire to ride the wave up. Many believe that at some point, there really is no ESG investing, as these considerations become incorporated across investing in the same way any other risk consideration is analyzed. In the meantime, as investor preferences for these stocks drive their prices up, investor returns will likely be positive as prices rise to a new equilibrium. So, maybe all we have to believe today is that interest in ESG will continue to increase.

Dana D’Auria, CFA, is co-chief investment officer at Envestnet.