The world can remain stuck in place for a decade and change more in one year than the past 10. The 2020 pandemic served as an accelerant for all the major trends influencing the RIA business for the decade—mergers and acquisitions, expanding use of technology and flex-time work.

Soon, we may be referring to 2019 as “back in my day.” Remember when advisors met clients in person? When we hired people who worked in the same city as us?

To view FA's 2021 RIA Ranking and the 50 Fastest Growing RIAs, click here.

Imagine the RIA office of the future. People are working in an office maybe three or four days a week. If a boss in St. Louis can’t find the right client service rep in town, no problem. She’ll hire one in Albuquerque who knows the business and can do everything she needs with clients over Zoom. Or hire a paraplanner in Omaha. She saves money on these hires—since locally sourced people might have been more expensive. The future already is closer than many advisors realize, as they don’t have to meet clients for every quarterly performance review.

Last year’s public health crisis also prompted clients to rethink their lives, careers and financial futures and ask themselves what really matters. As these priorities clashed, the complexities often led affluent Americans to seek out advisors. The upshot was a boom in business for well-positioned RIAs.

Deb Wetherby’s story for 2020 is not uncommon. She was not only surprised that her office could go all virtual—but says she saw no hiccup in client growth.

“We had probably our best year ever in terms of new client business,” says Wetherby, the founder of Wetherby Asset Management in San Francisco, adding that she brought in 45 new clients with $500 million in new assets (the firm now manages $6.9 billion for 550 clients). People at home had time to think of their finances, she says, and that prompted them to reach out to advisors. But, “I never thought a client would hire us without meeting us.”

Working from home has generated savings for many independent RIAs without any visible loss of productivity in the eyes of many senior executives. Whether it becomes permanent remains to be seen. But the flexible stance of many firms stands in stark contrast to financial services giants on Wall Street, many of whom are ordering all employees to return to the office after Labor Day. One clear takeaway is that it’s much easier for a business to track the productivity of 50 or 100 people than it is to monitor tens of thousands of employees.

Covid-19 left a path of human devastation in its wake that will likely change many things, including the way people do business. But there’s also a sense that the coronavirus merely hastened trends already in motion in the financial advice industry. Besides the work-from-home trends, RIAs also needed to speed up their tech spending if they had put it off. The rampant consolidation among firms with aging founders meant that more of them were likely thinking of selling, especially after the 2020 stock market rebound gave them an incentive.

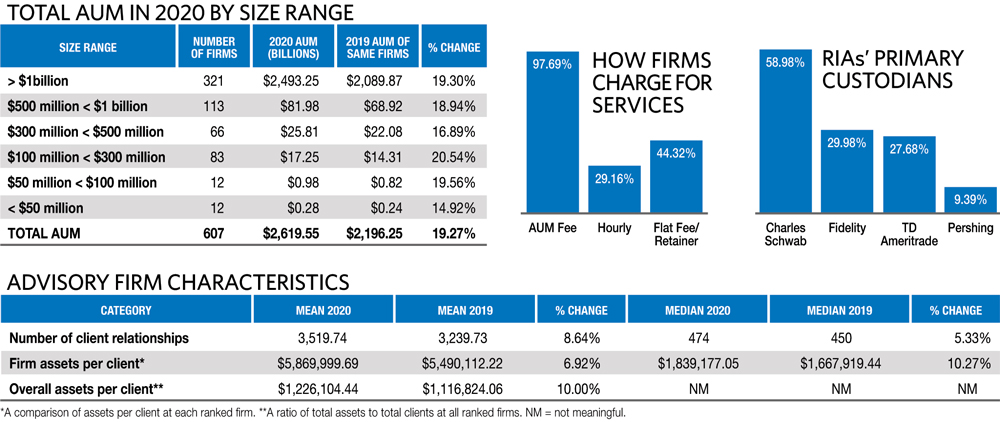

The quick market turnaround and a sea of private equity money in the space have sent RIA firms’ valuations rising to nosebleed levels. They are at the highest they’ve ever been, says David DeVoe, a mergers and acquisitions consultant with DeVoe & Co. who’s been covering the M&A space for almost two decades. He says firms with a billion or more in AUM are typically seeing valuations at above 10 times cash flow. (Others report the numbers can go as high as 18 or 20 times cash flow). Medium size firms of $500 million are seeing valuations at six, seven or eight times after rising from five to six times, says DeVoe, as RIA acquirers find sweet deals in this cohort while looking to go upstream. And even firms of $100 million have seen their cash flow valuation multiples go up a turn, he says.

The wave of consolidation is evident in this year’s RIA survey. Many firms that participated in the survey for more than a decade have been absorbed by giant consolidators, including CAPTRUST, Toronto-based CI Financial, Mercer Advisors, as well as other national firms like Creative Planning that have entered acquisition world. Mergers of other firms have produced eye-popping growth numbers. How successful these deals are is an open question. In other industries, the verdict on M&A has been decidedly mixed.

Things are happening on both sides of the ledger for firms hoping to remain profitable. Bill Bahl, co-founder and chairman at Bahl & Gaynor in Cincinnati, thinks there will be permanent structural changes in the way RIA firms operate. “We believe hours worked is higher in a remote setting than it might be in an office setting. If somebody lives 25 minutes from town … when you get ready to get in the car, park your car, get in the elevator, get your cup of coffee, you’re basically losing 45 minutes on each side.” That’s an hour and a half a day people could be doing client research, he claims. “People are working at a cadence that suits them. Which in some cases could be 10 o’clock at night.”

He says his firm invested a lot in technology last year to support multiple machines that people were using at both the office and their homes. “So our fixed costs went up,” he says, “and the cost to service that also went up because the IT services firm that we use charges us on a per device basis. So the investment management business is basically a fixed-cost business. There are very little variable costs in our business. … But the market also went up more than our fixed costs. So profitability in the industry I actually believe is more robust, certainly than it was a year ago at the bottom of the pandemic.”

Thus, he thinks 2021 will be more profitable than last year, which was more profitable than the year before, despite Covid-19. Bahl & Gaynor hired three people in the months after the shutdown, including a marketing/branding specialist, a senior portfolio manager and a financial planner.

Los Angeles firm Lido Advisors is one of those firms seeking to make strategic acquisitions, and in May the firm announced it had partnered with Charlesbank Capital Partners, a middle-market private investment firm, in pursuit of growth. “We don’t buy companies, we buy people,” says Lido’s chief executive officer, Jason Ozur. “So bringing in a strategic partner like Charlesbank will enable us to go upstream in our human capital acquisition strategy. … We are their first entry into the wealth management arena.” Lido, based in Century City, has 13 offices across the country in states like Arizona, Florida, California, Texas and New York.

There is fee compression in the industry, Ozur says. “The cost of running a company, and the cost of compliance and accounting and marketing … and analysts—those costs are going up, which is making it much harder for firms to maintain those types of cost structures. Which is why you’re seeing a lot of M&A.” The average age of the execs (in the 60s) is likely also fomenting this trend. Ozur says the average age of the partners at Lido is closer to the mid-40s.

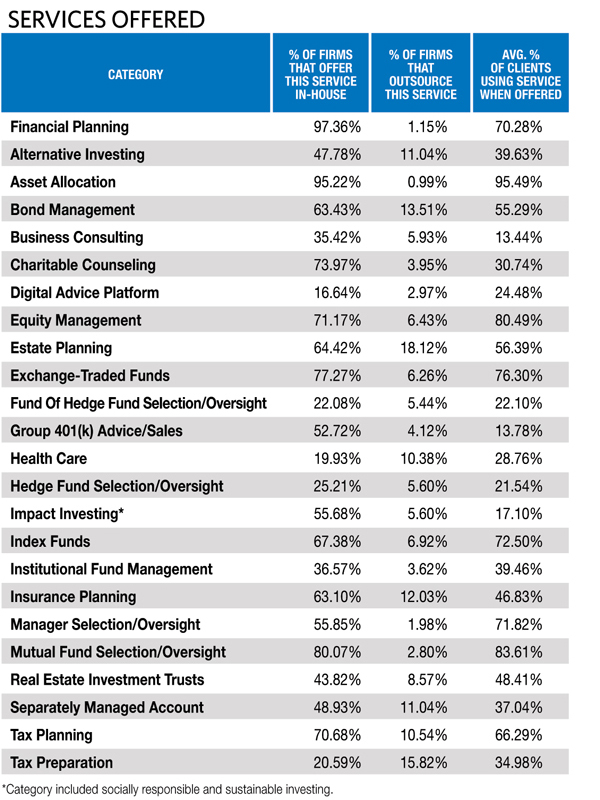

The firm came out of the family office space with a strength in alternative investments, but it has lowered its client minimums and is adding things like estate planning and financial planning and tax planning expertise. The firm is considering adding an insurance component as well. “We are definitely moving more to a full-service model than perhaps five years ago,” he says.

Lido made a handful of acquisitions of firms or individuals in 2020, including a firm called Quantum Capital Management and a bond team. Lido had been self-funding these up to now, before it partnered with Charlesbank.

Ozur says the pandemic likely scared a lot of advisors into wanting to sell their firms, because if they’ve lived through the financial crisis and then the pandemic, they don’t want to lose the opportunity to get their liquidity event. But he says that if firms aren’t growing, they are going to be less attractive acquisition targets.

“You see firms that try to value themselves on a multiple of EBITDA and they come to you with margins of 70%, which is unreasonable and not sustainable, and so you take a 70% margin and then you try to do a multiple of EBITDA, the price becomes ridiculous when you look at it on a multiple of revenue,” Ozur says.

Talent And Space

Has the coronavirus made advisors rethink what they’re spending on office space and human capital?

“Most of us have long-term leases, so it’s not like those are going to change instantly,” says Wetherby, but “I think we’re all rethinking our space needs. … My hope is that we can redirect some of those dollars into developing people.”

Bahl says it would have been a mistake not to go forward with his three important hires after the pandemic hit, but another respondent in the RIA survey bragged that their firm was able to raise profitability by cutting office and travel expenses and freezing hires.

And that comes at a time when labor markets are tight, Wetherby says, and costs are rising for human capital, RIA firms’ biggest line item. Wetherby was hiring in mid-June—looking for a wealth manager in her New York office and a client service associate in San Francisco. She says the firm is always hiring. She’s not the only one.

One large respondent in the RIA survey said, “We have five open positions and are currently finding it difficult to hire the right people.” Robert DiMeo, the CEO at Fiducient in Chicago, says his firm currently has 18 open positions.

With more megafirms developing, Wetherby says she hopes there will be more entry-level positions to absorb advisors coming out of universities and that they’ll be tracing more defined career paths—something that younger advisors have complained about in the RIA industry for years. She says tech is the biggest line item after people and space. And again, she says that hybrid work models could allow firms to seek cheaper staff. She says she’s compared entry level salaries and found they are about 40% higher in cities like San Francisco, Los Angeles and New York.

Dave Welling, the CEO of Mercer Advisors, says his firm signed up 1,100 new clients in 2020, and that the pace has accelerated, part of the firm’s strength in closely integrating the operations of its 50 offices (the firm started its acquisition strategy in 2016. It purchased 13 firms in 2020 and announced two more this year as of June, he says). As far as its new clients, “These are mostly people we never physically met, which is mind-blowing,” Welling says. The firm is headquartered in Denver but doesn’t have the bulk of its center of operations staff there, he says. The firm now has 17,000 clients and $32 billion in assets under management.

He adds that RIAs will see real estate savings after using hybrid work-from-home strategies. He says offices are going to a model that’s more similar to the medical profession: “The doctors or surgeons operate across multiple facilities to be close to the client. So if you want to book a medical appointment, I live in Colorado … I could sometimes choose the availability of the appointments of the facility in Denver or the facility in Boulder or somewhere in between. I have three or four facilities I could go to based on what’s going on in my day. Or if I happen to want to get away for a ski weekend, there may be a facility up in Vail.”

Meanwhile, back-office support to sign up new clients can be done remotely, freeing up the advisors from those chores. “You may have a superstar support person who’s in Scottsdale, and that’s better than having Door No. 3 unknown new hire that needs to be trained and may not stay with you.” This way, doors for talent can be opened up across networks, Welling says.

The firm recently hired a chief technology officer in Virginia and a chief marketing officer in Manhattan, and both will stay put in their home cities, Welling says.

Bob DiMeo at Chicago’s Fiducient (the former DiMeo Schneider) says the war for talent and the drive for scale are some of the bigger challenges facing the industry. There’s also a demand for investment research and proprietary asset allocation models that he says his firm sells to 50 other financial firms. “That practice is red hot and has been our fastest grower over the past two years.” The firm advises on $230 billion in assets, he says.

There’s also upward pressure on salaries across all industries, he says, and the RIA space is not immune. Firms that don’t shift to a hybrid work model might find it costly, he says. “We’ve added 20 people during the pandemic that never set foot in the office,” he says.

Money Chasing Higher Multiples

“There’s a lot going on with other people’s money,” DiMeo says. “When you look at the participation of private equity in our industry, you probably have some decisions being made that would not be being made if it were Bob and Eric going to their savings account and plunking these dollars down. The Fed’s zero interest rates have also likely played a part in valuations,” DiMeo says. “It feels to me like they are being priced beyond perfection.” If giant firms are paying multiples of 20, as some sources say, “Someday, that doesn’t make sense.”

Ben Harrison, co-leader of the wealth solutions business at BNY Mellon Pershing Wealth Solutions, a large custodian to the RIA space, says that if firms are turning to acquisitions to be their core growth strategy, they might be missing the big picture. “Organic growth is often overlooked, and they spend a lot of capital and time trying to find the right strategic, inorganic acquisition because they see the roll-ups doing it, they see the others doing it and growing quickly, and organic growth is the number one driver for valuation in the marketplace.”

Larry Roth, the managing partner of RLR Strategic Partners, has been working over the past five years with private equity investors, family offices and other investors in the RIA space and has seen 100 different transactions he says. He says he’s seen the giant firms’ valuations increase from 12 to 14 times EBITDA to 16 to 20 times EBITDA on much larger cash flow numbers. At the same time, the total cost of serving clients has generally declined.

“The cost at the customer level has declined or improved, but the actual profitability of the RIAs has generally gotten better,” Roth says. There are a couple of reasons for that, he says. “RIAs that use third-party managers for most of the portfolio construction have shifted their core holdings to ETFs and index funds and other low-cost options for the client. … If you’re charging 85 to 100 basis points five years ago, you’re probably still charging somewhere in that range, maybe two or three basis points less.” If you’re doing something simpler like managing large-cap stocks, you probably feel more fee compression in your core offerings, since you can’t charge more for hugging an index, he says.

Firms with $5 billion to $10 billion serving the mass affluent and high-net-worth segments, those focused on helping clients with their financial planning and goals and tax-managed portfolios, are running EBITDA to revenue margins in the 35% to 40% range. “Those firms are the firms that are most interesting to private equity,” Roth says. “Because private equity firms are using leverage themselves to buy these businesses, it’s really important that the firms are growing.” It wouldn’t be attractive to PE if the firm was growing with market, he says—lifestyle practices growing at only 3% to 5% a year.

Roth says the reason there are five times as many firms investing in the retail wealth space as there were five years ago is that 1) it’s cheap to borrow money right now, and 2) it’s hard to find other industries protecting 35% to 40% margins like retail wealth is.