The spread and acceptance of globalization has been an unrelenting force, but its march forward has lost some steam in recent years—is this the beginning of a new trend towards an outright contraction in globalization or merely a temporary deceleration?

We believe the broader trends of globalization remain in place and will continue to move forward as the benefits are widespread and far-reaching. Credit investors have long benefited from globalization, and now may want to prepare for an element of "regionalization," particularly given some of the supply chain disruptions we have seen as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic.

The Rise Of Hyper-Globalization

Globalization gained acceptance and became more prominent following the 1970s. The economic landscape quickly shifted towards free and liberalized international markets for goods, labor and financial capital.

A more global economy became a logical way for businesses to grow and establish additional economies of scale while tapping into new labor markets and eventually a new customer base.

Countries were swift in adopting new trading partners while lowering trade barriers and liberalizing their domestic markets. Supply chains became increasingly complex as first-world multinationals began to shift their manufacturing bases overseas. Several Asian countries became leaders among their peers and exported their way to "tiger economy" status while global financial hubs developed across the United States, Europe and Asia.

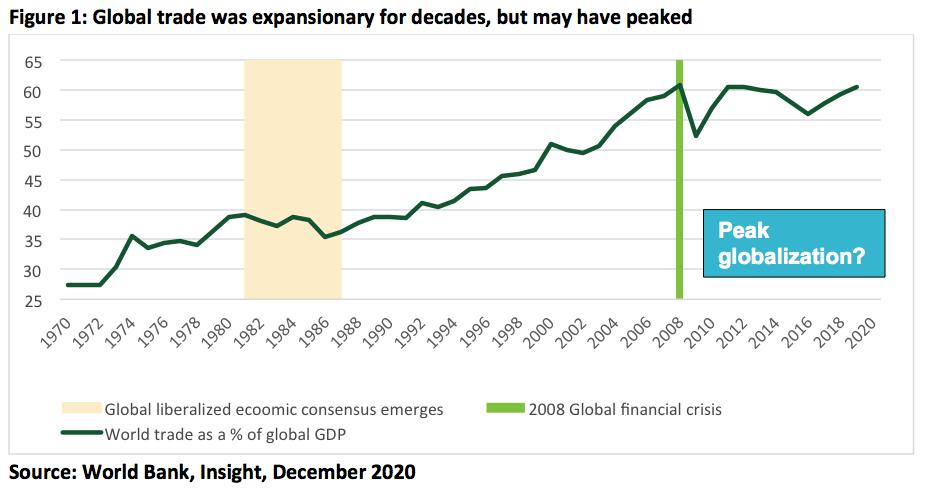

Global trade volumes steadily marched upwards before hitting a peak and flatlining after the 2008 crisis (Figure 1).

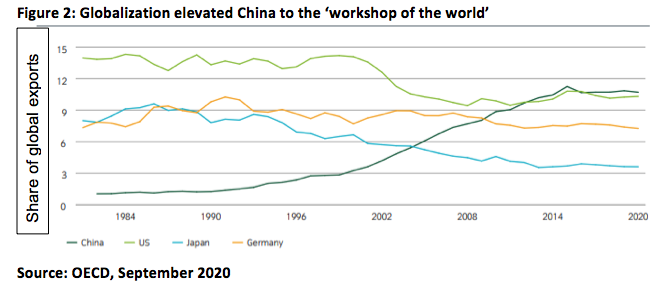

One nation’s meteoric rise in power was fueled by global trade: China. The world’s most populous nation opened its labor market to Western multinationals in the 1980s and eventually joined the World Trade Organization in 2001. China became the fastest-growing economy of the early millennium and its share of global exports overtook many advanced economies (Figure 2).

The United States and many other developed nations benefited from globalization on numerous fronts, but none was more obvious than the ability to leverage lower labor costs. Large, investment grade multinationals quickly saw their labor costs fall while their profit margins increase thus boosting equity valuations and enterprise value. Falling labor costs also heavily contributed to secular disinflation across the West, which persists to this day and is a positive for consumers’ disposable income.

The Fall Of Hyper-Globalization

The financial crisis of 2008 (a globally systemic crisis) exacerbated by the intricate links between not only financial sectors but also countries, took some of the wind out of globalization’s sails. Perhaps globalization took a backseat as the world experienced a contraction in growth, consumers deleveraging and an environment where fiscal austerity became a focus—shining a light on the widening inequality within the advanced economies.

Globalization then faced a stronger pushback from both the left and right sides of the political aisle within the United States as some global trading partners could be perceived as a competitive threat. This perhaps culminated in President Trump’s "America first" policy—which notably took aim at the emergence of China. Across the Atlantic, the UK’s "Brexit" vote affirmed similar sentiment.

We’re Shifting Toward Widespread ‘Regionalization’, Not ‘Isolationism’

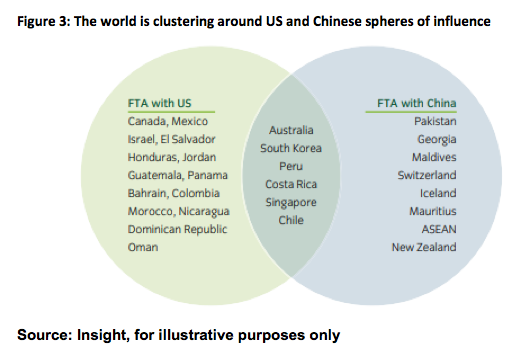

The end of hyper-globalization does not imply a retreat into global isolationism. Instead we believe a more likely scenario is that the world will cluster more strongly into regions around so-called ‘spheres of influence’ based upon economic and geopolitical ties.

The European Union is perhaps the largest example of a multilateral regional bloc, with Germany and France at its forefront. Future regional clustering is likely to occur around the United States and its emerging geopolitical and economic rival, China. Many countries are aligning with one, or the other, while others attempt to play a careful balancing act (Figure 3).

For example, the United States has (through the USMCA trade pact) strengthened its economic ties to Mexico and Canada. The USMCA includes requirements for localized production and also grants the United States with the ability to veto any free trade agreements between either Mexico or Canada with China.

China, meanwhile, has been busy with its "Belt and Road" initiative, a large-scale infrastructure plan designed to open up and establish improved trade routes across Asia, Eastern Europe, Africa and Latin America. There is, however, one initiative, the Trans-Pacific Partnership, that is a counter-attempt by certain (largely Asian) nations to form a cohesive economic bloc outside of China’s influence.

Multi-national corporations are underway in shifting towards more localized production and some are shifting production out of China to its neighboring nations. This will likely unfold in a staggered process with some industries taking longer than others to effect the transition. China’s current status as "workshop of the world" is a result of decades of investment and government support aimed towards building huge industrial parks, training workforces and strengthening connections between massive ports and modern logistical networks that would likely take many years to replicate elsewhere.

Corporations operating in the United States may find that re-localizing production may not be straightforward. Government assistance may be needed to subsidize the increased cost of domestic production. This could come in multiple forms, some being direct tax credits or tax incentives, and preferential treatment for domestic producers to help gain a competitive advantage.

Consider The Winners And Losers

Globally, we believe South Korea, Poland,and Malaysia are likely the winners should the effort to diversify away from China persist. Mexico and India would also stand to gain from this shift on a longer-term basis.

In the United States and other more advanced economies, the winners should be the sectors that directly compete with Chinese exports; the sectors that have inelastic enough demand to pass thru higher labor costs to its consumers. However, the areas or sectors of the economy where the demand for goods are more elastic to price changes are less likely to have the ability to pass the increased cost on to consumers and thus will face margin compression.

Localizing production within a developed nation should mean upward pressure on prices given rising input costs, which has the ultimate effect of eroding disposable income. This effect could be partly offset with higher domestic wages given the expected increase in demand for domestic workers. How these forces ultimately play out will likely vary by location and sector.

Some sectors of the economy may be able to dampen the effect of higher labor costs through increases in productivity such as automation. This could be a boon for business investment and productivity growth but will likely vary by sector.

Regionalization May Have Far-Reaching Impacts On Parts Of The Corporate Credit Market

Fixed income investors, such as those invested in Core or Core Plus strategies, are partly invested in large, investment grade multinational corporations that have benefited from the hyper-globalization of recent years. Over the next decade, the impact of regionalization is likely to have long-term impacts on their fixed-income portfolios. However, these effects are unlikely to be uniform across all sectors or by individual credit.

At Insight, we believe fixed-income investors need to consider managers that focus on bottom-up fundamental analysis and are highly selective in their investment approach. Studying fundamentals can help investors understand how business’ supply chains are evolving, the intentions of management teams and the likely effect on credit metrics.

In our view, it is the diligent investors that will be best placed to maximize the opportunities of regionalization while avoiding the pitfalls.

James DiChiaro is senior portfolio manager at Insight Investment.