The Great Shift

Let’s make a big assumption. We really are in the process of not only a great shift toward reflation, but toward a new inflationary regime. What is this like, how can we tell, and what does the future hold?

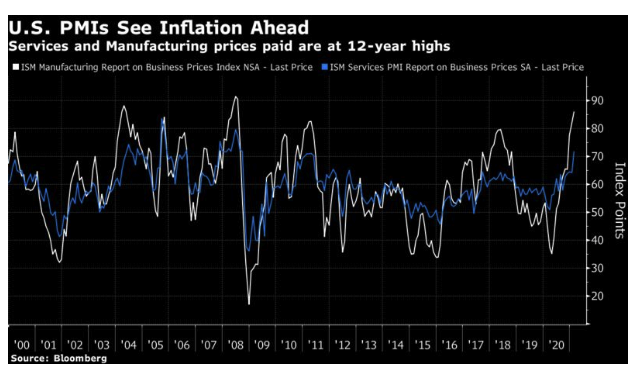

If you want to argue for a new inflationary paradigm, there is plenty of evidence. This week’s U.S. purchasing manager surveys found prices in both the manufacturing and services sectors at their highest levels since the eve of the global financial crisis, and rising fast. These have been good leading indicators of inflation in the past:

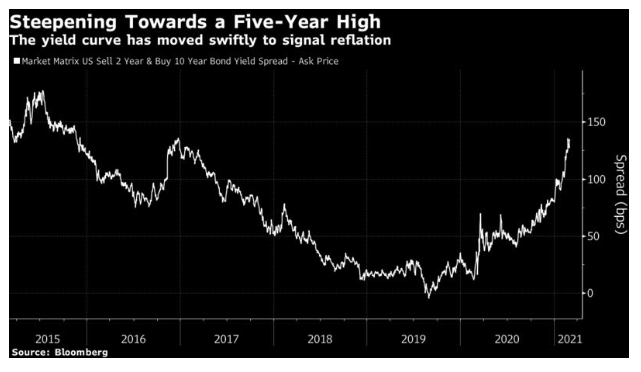

Meanwhile, bond yields climbed sharply across the world, while yield curves steepened. In the U.S., the spread between two- and 10-year yields is its widest in more than five years, barring only a few days after the election of Donald Trump in late 2016:

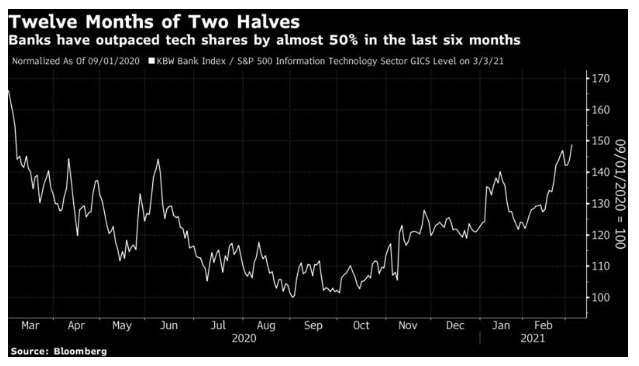

Politicians strengthened traders’ convictions. Wednesday’s annual U.K. Budget, which saw a promise of even more aggressive spending, suggested that fiscal and monetary policy will at last act in unison. Within the stock market, banks (which tend to benefit from higher yields) extended their outperformance of technology stocks (which have prospered from the perception that they can help defend against a slow economy). Since the start of September, banks have outperformed by almost 50%:

But if the broad case for reflation is clear and widely accepted, there is still a question over whether this is a true “regime change.” For four decades, inflation has stayed low and under control, while bond yields have declined. Even with the sharp moves of the last few months, those trends remain intact. Many forces for deflation or disinflation also remain in place. Workplace automation continues apace, reducing prices and the bargaining power of labor.

So, what follows is an attempt to put together a strong case that an inflationary regime change is indeed upon us. To start, let’s return to the last one, some four decades ago.

What A Regime Change Feels Like

It’s difficult to recognize a regime change in real time. My exhibit is America in Search of Itself by the great political journalist Theodore H. White. In it, he chronicles all the presidential elections from 1956 to 1980, and explains the forces that contributed to the election of Ronald Reagan in 1980, one of the sharpest political changes of direction the West has seen since the war. He devotes an entire chapter to “The Great Inflation,” which, he said, touched everyone and was “the main thrust of Ronald Reagan’s attack on Jimmy Carter.” The following passage is a beautiful piece of journalistic prose:

“Inflation has no date of beginning. Inflation is the cancer of modern civilization, the leukemia of planning and hope; as with all cancers, no one can say when it begins or how fast it may spread. It is a disease of money, and when money goes, order goes with it. Inflation comes when a government has made too many promises it cannot keep and papers over the shortfall with currency which, ultimately, becomes confetti—and faith is lost.”

Writing in 1982, White wasn’t concerned with hyperinflation, as seen in the Weimar Republic or Zimbabwe. U.S. inflation had peaked in 1980 just above 14%. Yet his work sounds similar to much prose written over the last decade about the evils of inequality, long-term unemployment, the gig economy, and deaths of despair. He was writing angrily about a condition that had become an intolerable part of life, and also with no grasp that it had already peaked. By the end of 1982, the year he published, it had dropped all the way to 3.8%. Paul Volcker had been appointed to chair the Fed by Carter in 1978, and was in the process of winning the war on inflation—but amazingly, a great journalist could write about inflation in 1982 without ever once mentioning his name.

White gets across that inflation appeared inevitable and unavoidable. By the summer of 1979, he says, “no other issue could rival the inflation as a pressure on the American mind.” Conversation before the 1980 election was “stained and drenched in money talk, by what it cost to live or what it cost to enjoy life.” White talks about how inflation had come to divide the nation, and how all politicians shared a desperate aim to beat it. Reagan’s campaign had many themes:

But underlying them all was the appeal to the Untermensch of politics: The government is cheating you, inflation is stealing away from you the value of your dollars.

Four decades later, with the Fed established as by far the most important institution in the global economy, people talk in exactly the same kind of apocalyptic terms about how lack of inflation leaves us being cheated by a thieving government. Four decades from now, it’s easy to imagine that historians will think it obvious that the current deflationary regime had become intolerable, and that it was already being shifted.

How To Change A Regime

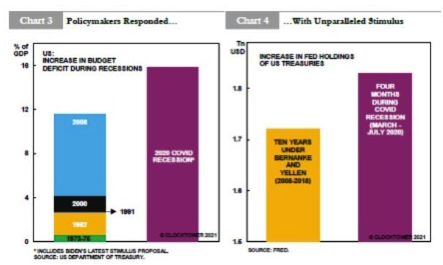

Inflation psychology is difficult to change. But last year might do the job. The monetary and fiscal response was of a different order of magnitude from the crises that preceded it. The following chart is from Marko Papic of Clocktower Group:

Meanwhile, the Fed’s intent is clear. Chairman Jerome Powell stresses the urgency of dealing with unemployment and the inequities it causes. The following comments are quoted by Dylan Grice of Calderwood Capital in his Popular Delusions newsletter:

“The big picture is still that we’ve seen … three decades, a quarter of a century, of lower and more stable inflation and we’ve seen really the last decade be characterized by global disinflationary forces and large advanced economy nations struggling to reach their 2% inflation goal from below...

We have had inflation dynamics in our economy for three decades which consists of a very flat Philips curve, meaning a weak relationship between high resource utilization, low unemployment and inflation, but also low persistence of inflation, critically … of course those dynamics will evolve, but its hard to make the case why they will evolve very suddenly, in this current situation.

I described our new framework and our guidance, in major part we are looking at actual inflation, we want to see actual inflation, and part of the reason for that is that all during the long expansion, many of us—and that includes me—were writing down a return to 2% inflation, and maybe a mild overshoot, year after year after year. And year after year after year, inflation fell short of that. So we have tied ourselves to realizing actual inflation.”

“Volcker said he was going to tame inflation, unemployment be damned,” says Alex Lennard of Ruffer LLP. “Now it’s the other way around. I don’t think people have quite realized that you’ve had this huge change in the mandate of policymakers.”

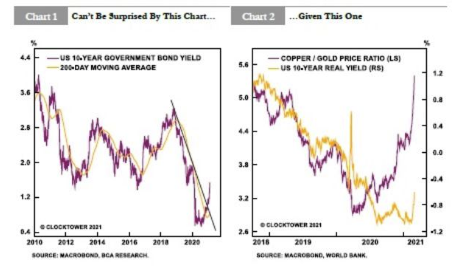

Added to this, there is now an agreement on fiscal expansion. Politicians around the world appear to be “going big.” Meanwhile, as Papic of Clocktower shows, the underlying market moves have been suggesting a change in direction for a while:

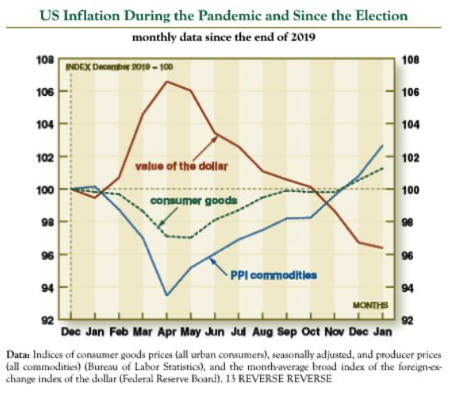

As for the constituent parts of inflation, this chart from David Ranson of HC Wainwright & Co. demonstrates a clear turn last year, which in the U.S. has been accelerated by the weakening of the dollar—a phenomenon that is widely expected to continue:

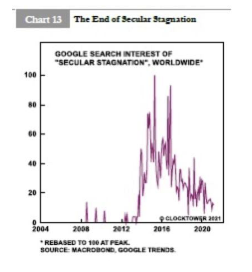

At a more subtle level, while concern about inequality and the hollowing out of the middle class occupies politicians across the spectrum, worries about “secular stagnation” have quietly disappeared:

Indeed Lawrence Summers, the former Treasury secretary who coined the phrase, has in recent weeks been cautioning about the risks of overdoing fiscal stimulus. More or less all the conditions for changing a regime are in place. Many still think that deflation and inequality are deeply ingrained and cannot be averted—but then that’s what Theodore H. White thought when the last great inflationary regime shift was already under way.

What To Do

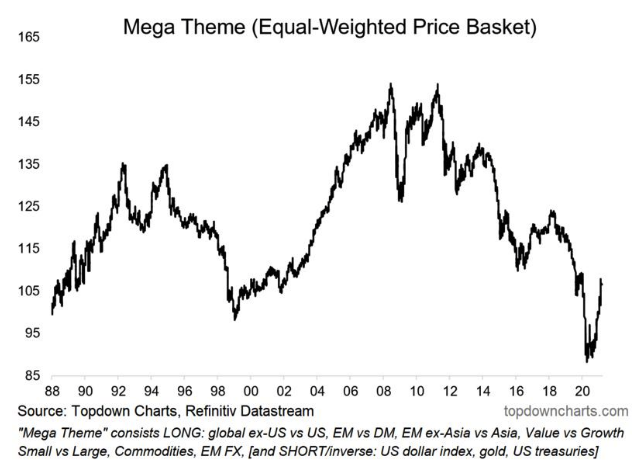

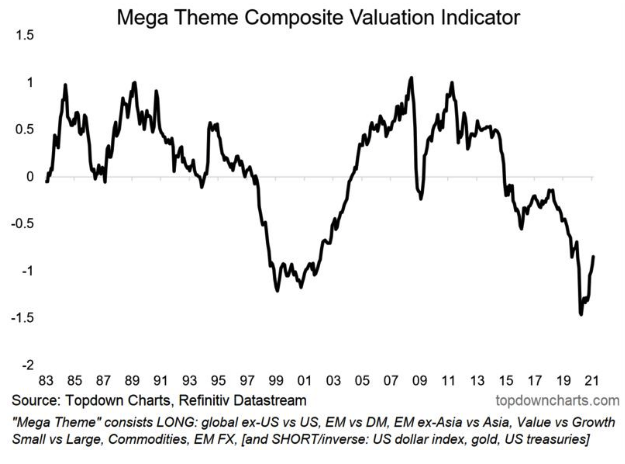

If a regime change is upon us, what do we do about it? For now, there is a close comparison with the market that preceded the GFC. That decade was driven preeminently by the growth of China, and numerous trades tied to the country’s strength did well. Part of the 2008 disaster sprang from the fact that investors thought they were diversified when in fact they had just made the same bet many times over in different asset classes. The following chart from Topdown Charts of New Zealand shows the performance of an equally weighted “mega-theme” portfolio, of 10 separate trades. These include betting against the U.S., plunging into value stocks, and investing in the emerging markets and commodities complex:

China won’t be the leader to the same extent this time, but the same trades should all prosper in a broadly reflationary environment, this time fueled by expansionist policies and attempts to build green infrastructure. This cycle could play out very quickly, Papic of Clocktower warns, and might easily end within a year or two with some kind of “fiscal cliff” drama, as politicians balk at continuing to pay the bill. The basket’s valuation suggests the trade could have a long way to go:

By the reckoning of Callum Thomas, Topdown Charts’s head of research, this mega-theme basket is only slightly more expensive than it was at its turn-of-the-century low—when a massive rally lay ahead.

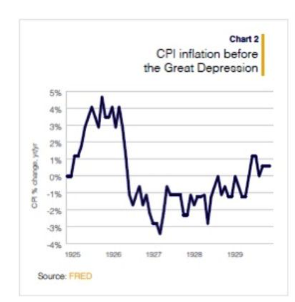

What of the risk of a bubble from here? It’s substantial, as money is already plentiful and seemingly about to become more so. Grice suggests that Powell’s approach leaves him open to making a “new old mistake,” in which the Fed takes comfort from low and stable inflation and thereby fails to act against a build-up of speculation. This is the inflation pattern that lulled the Fed into a false sense of security ahead of the Great Crash of 1929:

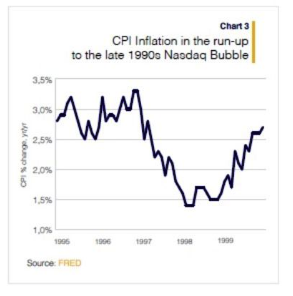

And these are the inflation numbers that helped dissuade the Greenspan Fed from a decisive attempt to puncture an asset bubble (the “irrational exuberance” speech came at the end of 1996) ahead of the internet mania:

The risk is that while the Fed waits for inflation to average above 2% for an extended period of time, asset prices in other parts of the economy will have gone completely bonkers. That raises the danger of a crash, to add to the risk of inflation destroying portfolios.

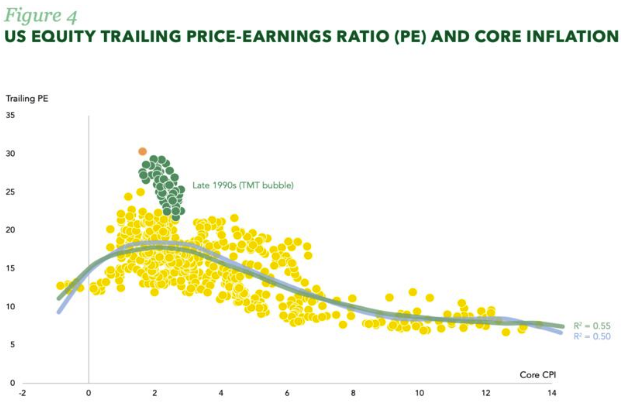

If inflation persists it will be bad for stocks as well as bonds, particularly given the extremely expensive valuation from which they start. (Before anyone pipes up about low bond yields, remember they will no longer be low, leaving stocks exposed.) Henry Maxey, investment director of Ruffer, calls this “Jurassic Risk”—a newly mutated dinosaur could be on its way to chomp investors’ portfolios. He adapted the following chart, in which the orange dot shows where we are now, from work by Gerard Minack:

In the long run, the Ruffer argument is that we are facing the death of the 60/40 portfolio. Such a balanced allocation is awful if both stocks and bonds go down. But what else is there? Inflation-protected bonds remain under-appreciated and top the list, followed by equities that can benefit from the conditions ahead. Ruffer has also experimented with cryptocurrencies. Much of the current institutional willingness to examine the crypto world comes from the sense that they will have to try something beyond stocks and bonds.

One final problem for asset managers is, of course, the need to guard against the distinct possibility that somehow the regime change doesn’t happen after all. Unfortunately, it will continue to be necessary to guard against the risk of being wrong. But there’s a strong and reasonable case that a regime change is under way.

Survival Tips

Continuing on the recent theme of music from movies, which has the best soundtrack? I’m not thinking about musicals here, but films with a really interesting collection of sounds playing in the background. My cautious nomination would be the Molly Ringwald teen classic Pretty in Pink (a choice that gives away my age, but such is life). Apart from the title track by the Psychedelic Furs and the OMD classic If You Leave that rolls over the prom at the end, it also includes gems like Left of Center by Suzanne Vega, Shell Shock by New Order and Bring on the Dancing Horses by Echo and the Bunnymen. And Please, Please, Please Let Me Get What I Want by the Smiths, which I linked to not long ago. It all suits me. Any better sound tracks out there?

John Authers is a senior editor for markets. Before Bloomberg, he spent 29 years with the Financial Times, where he was head of the Lex Column and chief markets commentator. He is the author of The Fearful Rise of Markets and other books.