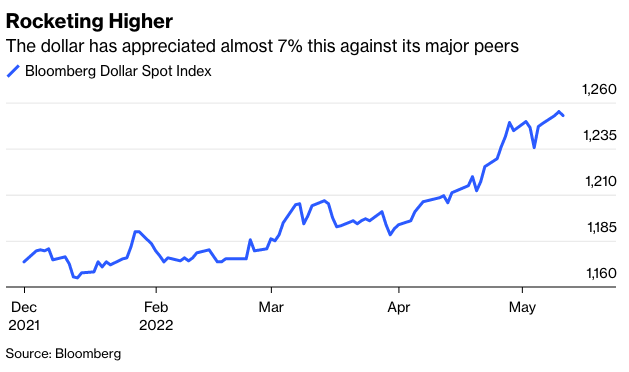

In 1995, Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin asserted that a strong dollar is in the U.S. national interest, a mantra repeated by each of his successors. They’re partially correct since the effects of the robust buck, which has soared this year, help some while harming others.

The rising greenback makes U.S. imports cheaper, favoring American consumers. Ditto for U.S. businesses that import manufactured goods and services, important offsets to surging domestic inflation. Commodities are the exception. Of my list of 45 that are traded internationally, 42 are priced in dollars, including crude oil and other hydrocarbons; corn, wheat, soybeans and other agricultural products; base metals such as lead, zinc, copper and aluminum; and gold, platinum and silver. The three exceptions are palm oil, priced in Malaysia ringgit, wool traded in Australian dollars and amber priced in Russian rubles.

So, the rising dollar doesn’t affect their dollar prices directly, but does make them cheaper to Americans indirectly as higher dollar costs reduce global demand by pricing foreigners with weak currencies out of the market. In effect, the robust greenback depresses economic growth.

The stronger dollar also retards American exporters by making their products more expensive for foreign buyers in their own currencies. Microsoft Corp. said in its earnings report last month that a strong dollar reduces its revenue. It also forces domestic producers to cut their costs and shave their profit margins in order to compete here and abroad. Conversely, foreign exporters to the U.S. can reduce their dollar prices somewhat and still increase their revenues in their own currencies.

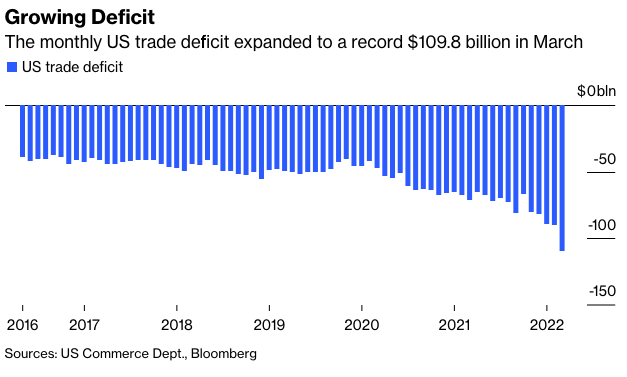

The detrimental effects of a robust buck on American multinationals are shown in the foreign trade numbers. Since the beginning of 2020, U.S. exports have risen from $2.46 trillion to $2.91 trillion but imports jumped from $3.01 trillion to $4.22 trillion. So, the foreign trade deficit expanded from $546 billion to $1.32 trillion. Faster economic growth here than abroad also hypes U.S. imports.

With the pandemic subsiding, Americans are re-emphasizing services including foreign travel, and their dollars buy more yen, euros and sterling to spend abroad. But U.S. businesses that cater to foreign visitors such as hotels, resorts and car rental companies find visitors from abroad with fewer dollars to spend.

About 80% of $100 bills reside outside the U.S., especially in Russia, according to Markos Kaunalakis, a visiting fellow at the Hoover Institution. As of 2019, $31.5 billion worth of portraits of Benjamin Franklin were stashed in mattresses and money belts. Since the cost of printing those bills is tiny, the seigniorage is considerable and provides a huge windfall for the U.S. Treasury.

At the same time, the robust buck is distracting attention from cryptocurrencies. Bitcoin’s price is down 54% from its $67,802 peak last November to $31,299. Stablecoins are meant to keep their value at $1, but TerraUSD, the third-largest stablecoin, plunged to 30 cents on May 11 as holders doubted that its peg to the rising dollar could be held.

As the dollar climbs, U.S. investors can buy more foreign securities, but that also puts pressure on domestic companies that produce superior earnings in dollar terms. And foreign investors in American securities have the wind at their backs as the robust buck gives them currency translation gains on top of dollar-denominated investment results. Take 10-year sovereign yields, where Treasury notes provide higher yields than their counterparts in 15 other developed countries. The 3.04% U.S. yield is 2.81 percentage points better than Japan’s 0.23%, 2.14 points above Switzerland’s 0.90% and 2 points higher than Germany’s 1.04%.

The strong dollar isn’t universally helpful to American consumers and investors. Still, in addition to being a haven in a sea of global turmoil, it does tell investors worldwide that the U.S. is the best place to be.

Gary Shilling is president of A. Gary Shilling & Co., a consultancy. He is author, most recently, of The Age of Deleveraging: Investment Strategies for a Decade of Slow Growth and Deflation, and he may have a stake in the areas he writes about.