I loved high school geometry. Shapes had intrigued me since I was very little, and the notion that you could express their properties mathematically appealed to my quantitative nature. I also enjoyed the logic in the Euclidean system of proofs, which build from simple truths to more complicated ones.

In geometry, the shortest distance between two points is a straight line. In economics, there are no straight lines: everything is a curve. The curves are difficult to draw, and they shift frequently. Thousands of curves describe an economy, and these have to be added and reconciled to find equilibrium. Truth in economics is not easily proven.

As we look ahead to a post-pandemic equilibrium, four curves will describe the arc of economic recovery. Movement along these frontiers will determine how fast we arrive at a new normal.

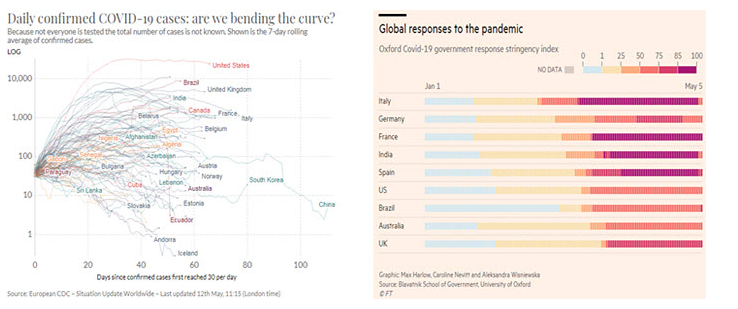

The first curve describes the progress of the pandemic itself. At the outset of an outbreak, cases grow exponentially; preventative measures slow this growth rate and “bend” the contagion curve. This calculus has been particularly important with COVID-19, given constraints within health care systems around the world.

Once the medical statistics improve, the second curve will be traced by public health policy. How soon will officials allow more freedom of movement, and what lingering restrictions will they require to ensure adequate safety? The last thing that anyone wants is a relapse, which would require the reinstatement and/or reinforcement of closure orders. Such a retreat (which we have already seen in several Asian countries) would be damaging both commercially and psychologically.

Societies do not have to wait until new cases fall to zero before reopening. But the risk of infection has to be brought under firm control. That risk informs decisions by economic actors that will determine the rate of commercial recovery.

A number of countries (and regions within countries) have begun the process of reopening. Each provides data points that can be used by others to calibrate the recovery process. We’re all anxious to restore normalcy in our economy and in our own lives. But citizens will have to accept that ultimate freedom will not be possible without near-term limitations.

The third curve describes return-to-work patterns in the private sector that will emerge once the public sector has provided some clearance. Each company’s decision to resume operations is a complicated one that depends on answers to a number of questions, including:

• Will there be sufficient demand, or traffic, to justify reopening? And if there is, will it be profitable?

• Are supply chains sufficiently repaired so that material can get in and out of plants?

• Will physical changes to the workplace be needed to comply with distancing guidelines?

• What other necessary steps will make customers comfortable enough to come back?

• Are employees ready to return? Do health worries or family constraints make that prospect difficult?

What legal and reputational risks might arise if the business is seen as a nexus of new contagion?

While standards will certainly emerge for all to follow, each business must make its own decision. As one chief executive noted recently, “if you think shutting the economy down was hard, reopening it will be even harder.”

The final curve describes consumer behavior. Individuals will have to decide whether they are comfortable resuming their routines. We’ve all been coached to be cautious, and so it may be a while before we dine out, take mass transit, attend a performance, stay in a hotel or fly somewhere. Damage done to household finances during the pandemic may limit what we can afford.

When you lay the four curves end to end, you have a trajectory that is more gradual than sudden. Complicating matters further is that curves can look different in different places, which presents challenging logistics for firms that rely on international or interstate commerce. Absent a vaccine (which will not likely be available anytime soon), residual risks on several levels will continue to limit economic activity.

This outlook has important implications for policy. Many programs implemented immediately after the start of the pandemic were crafted as short-term bridges; with the spans now needing to be lengthened and reinforced, legislatures around the world will have to consider extending and enhancing support programs. This will not be an inexpensive proposition.

A slow recovery could present existential risks for the sectors of the economy most seriously impaired by the pandemic. Airlines, hospitality, entertainment and education are among the industries that might be the focus of specific policies to help them through a more prolonged interruption.

There could certainly be developments that cause a change of course. The arrival of a vaccine would be a favorable game changer that reduces risk and accelerates recovery. On the other side, a renewed coronavirus outbreak later in the year, potentially caused by a more pernicious mutation, would be a setback.

While all geometric shapes have their charms, my favorite was the triangle. I enjoyed proofs of congruence, and the special case of the right triangle founded my fascination with trigonometry. The triangle offense used by the great Chicago Bulls teams of the 1990s, celebrated in the documentary The Last Dance, was a joy to watch.

Unfortunately, the upcoming economic recovery will not be described by the “V” formation that is central to triangles. Instead, twists and turns will define the shape of what’s to come.

Gimme Shelter

Quarantine has made us view our homes in a new light: They have taken the place of our offices, our restaurants, our houses of worship. Our homes have never been more important. Unfortunately, the current crisis is making it difficult for many families to hold onto their homes. And that will cause trouble for key players in the U.S. mortgage market.

The CARES Act included a protection for homeowners. Any mortgage guaranteed by Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, or other public agencies (collectively, the government-sponsored enterprises or GSEs) can enter forbearance at the borrower’s request. No questions are asked; by simply asking the servicer for relief, six months of payments are deferred. At the end of that period, another six months is available upon request.

Forbearance is not forgiveness, and those missed payments will still come due. The law does not specify a repayment approach, which has led to a series of mixed messages for borrowers. No good would come of expecting them to make a six-month lump-sum payment at the end of the forbearance period. Rather, the mortgage notes are likely to be extended, with today’s missed payments appended to the end of the loan.

Unlike homeowners, renters have not been granted protection in national legislation. Many cities and counties have stopped eviction proceedings, allowing people to stay in their rented homes for a time. As of the first week of May, the National Multifamily Housing Council estimated that 80.2% of renters had partially or fully paid their May rent, surprisingly not far removed from the 81.7% that had paid at the same point in May 2019. However, the stress that tenants are feeling will not abate quickly.

In April, the majority of households received the cash stimulus afforded by the CARES Act. That lifeline payment helped keep many renters solvent, but it was just a one-time payment. Similarly, many tenants are probably benefitting from the expanded unemployment insurance benefit afforded by the CARES Act, but that supplement will expire at the end of July. Rent strikes are becoming more common, as tenants exhaust their financial resources.

Thus, we have two categories of payees receiving fewer payments: Landlords and mortgage servicers. Each of these parties has their own bills to pay.

Landlords who own properties outright face a risk of lost revenue if tenants can’t catch up to their rent payments. Large landlords that issue equity or bonds to finance their operations will get by; smaller landlords may feel the pinch. At best, they may qualify for a Main Street Business Lending Program loan to carry them through the crisis, but that loan will need to be repaid.

Landlords may still carry a mortgage on their properties. About 46% of multifamily mortgages are guaranteed by the Fannie and Freddie, and these are eligible for the same forbearance that single-family homeowners qualify for.

Mortgage servicers collect monthly payments from mortgagees and disburse them to holders of the mortgage-backed securities that contain the loans. Those servicers are now in a pinch: They are obligated to make coupon payments to bond holders on schedule, but they are not receiving cash to fund those payments. Non-bank servicers could be facing serious liquidity and capital trouble; they may be the next group in need of a lifeline from the Federal Reserve.

A spate of foreclosures intensified the damage from the last recession. Measures like forbearance show that policymakers have learned from that experience. But these steps don’t eliminate the stress, they just shift it. The U.S. mortgage industry may once again require reinforcement.

Blame It On Rio

Initially, epidemiologists had hoped that warm-weather countries would not be deeply touched by the coronavirus. But with around 180,000 confirmed cases and over 12,000 COVID-related deaths, Brazil is staring at a full-blown health emergency and is at risk of an economic meltdown.

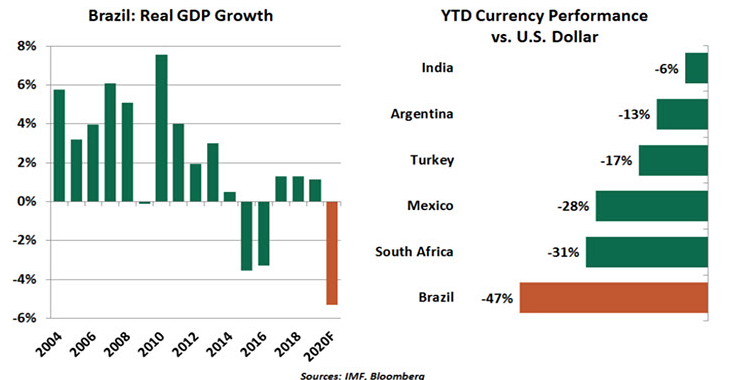

Though Brazil’s mortality rate is lower than that of many advanced and emerging economies, the density of its population and the weakness of its medical system create significant problems for public health. The country’s economic health is also in question: growth has failed to reach the dynamic levels seen early in the last decade, when Chinese demand for commodities made Brazil an emerging star. Falling mineral and crop prices and inadequate infrastructure have taken a severe toll on activity and confidence in Brazil.

Today, the country is facing a severe recession as a result of the virus’s spread and lower commodity prices. Incomes have been ravaged. The Brazilian real (BRL) has fallen to record lows against the dollar and is the worst performing currency of 2020. Even before the outbreak, Brazilian markets were already in a furrow and are currently down 33% on a year-to-date basis. Risks for the financial sector are rising as proposals (including limiting credit card and overdraft interest rates) against financial institutions are gaining momentum.

The Brazilian government has announced fiscal measures equivalent to 7% of gross domestic product (GDP) in the form of direct cash transfers, tax deferrals, expansion of social safety nets and credit lines to small and medium-sized enterprises. The central bank is doing its bit as well, slashing overnight rates by 150 basis points to a record low of 3.0% this year, with more likely to come. With a fiscal deficit of about 6% of GDP and government debt around 80% of GDP, the economy is in a precarious state. Large-scale measures would revive concerns about Brazil’s fiscal position, something that policymakers were hoping to have put to rest with last year’s pension reforms.

The administration’s lax attitude toward the outbreak has alarmed citizens and outsiders alike. The dismissal and resignation of key political figures and investigations surrounding President Javier Bolsonaro and his family have also created political turmoil. Brazil has lost its luster, and is in danger of becoming a shadow of its former self.

Carl R. Tannenbaum is executive vice president and chief economist at Northern Trust. Ryan James Boyle is a vice president and senior economist within the Global Risk Management division of Northern Trust. Vaibhav Tandon is an associate economist within the Global Risk Management division of Northern Trust.