Year-end tax planning isn't what it used to be. Usually, practitioners can at least say they have a handle on the relevant rules. But not this year.

"It's tough to advise clients because we're waiting to see what income tax rates are going to be in 2011," says Mike Tedone, the chief compliance officer at Filomeno Wealth Management LLC in West Hartford, Conn. "We're trying to determine whether it makes sense to accelerate income into 2010, especially long-term capital gains."

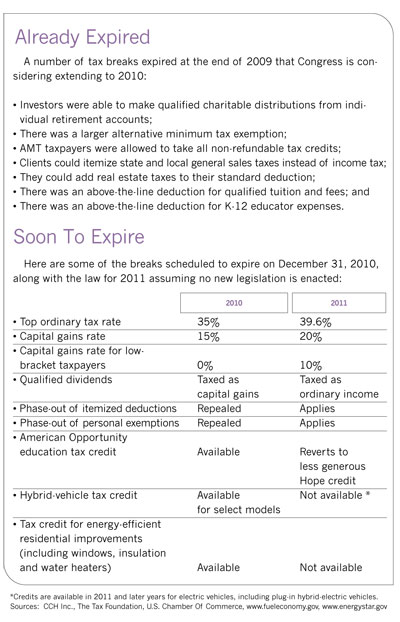

The question is whether the Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2001 will be allowed to sunset after December 31. If it does, tax rates will climb in 2011. That means advisors will want to bring income forward into 2010 wherever they can.

President Obama has proposed allowing the rates to rise in 2011 only for joint filers with incomes above $250,000 (or single filers with incomes of more than $200,000). Congressional Republicans have thumbed their noses at that idea, and classic Washington gridlock could keep new legislation from being enacted, which means EGTRRA's goodies will perish. But even if that occurs, in January the new Congress might reinstate the lower rates and other expiring breaks, says Mark Luscombe, a federal tax analyst at CCH Inc. in Riverwoods, Ill.

The 2001 act's demise would also resurrect the phase-out of itemized deductions, which is gone this year. Luscombe says the administration wants to restore the phase-out for taxpayers with incomes greater than the same high-income thresholds, and advises clients who might be subject to the phase-out in 2011 to think about accelerating deductions such as charitable contributions and real estate tax into 2010. You have to determine which is better: a full deduction in 2010 taken against lower tax rates, or a potentially smaller deduction in 2011 taken against potentially higher rates.

Besides the 2001 act, other sections of the tax code are in flux, too, including the so-called patch necessary for keeping millions of taxpayers from the clutches of the alternative minimum tax. "For 2010, the AMT exemption amount has reverted back to $45,000 for joint filers" from $70,950 in 2009, Luscombe says. Moreover, the ability to take certain non-refundable credits against the alternative tax has also expired. If a patch for 2010 is not enacted, the Tax Policy Center puts the number of AMT taxpayers at nearly seven times last year's figure.

(The sidebar recaps some of the breaks that are coming and going and may be coming back.)

Roth Conversions: The Big No-Go

A lot of hoopla surrounded the eligibility this year of all taxpayers, regardless of income, to convert traditional individual retirement accounts to Roths. But so far few clients have been willing to cough up the ordinary income tax that's due on a conversion, even if they have the funds outside the account to cover it. As one high-net-worth client put it to Cass Chappell, the president of Chappell, Mayfield & Associates in Atlanta, "I agree I'm probably going to pay higher taxes in the future, but I don't care what the numbers say. I want to hang on to my money."

Some Tea Party clients with a great fear of future taxation have the opposite problem and would rather pay now, in an odd twist, even if it's not appropriate for them. Raleigh, N.C., planner Gerald Townsend reports, "I've had to calm down some of those and say, 'You act like you're making $500,000 a year when you're making $50,000. Your tax bracket is not going to zoom upwards in retirement but will probably be lower than it is today, so don't get emotional and convert and pay a lot of taxes.'"

When you really run the numbers, converting to a Roth is not convincing in very many cases, concludes Townsend, the president of Townsend Asset Management. "You need a special circumstance," he says, such as business losses to offset the income created by converting, or a high-net-worth client who has funds she'll never need.

Even if the circumstances are right, some advisors still tread cautiously. Tedone recommends conversions only if beneficiaries can draw down the IRA over their life expectancies. "When the Roth is going to be the only inheritance and the beneficiary needs it to live on, a conversion probably doesn't make sense," he says. "The biggest benefit comes when you stretch the account as long as possible. Our clients who converted had optimal fact patterns."

Chappell plans to revisit Roth conversions with his wealthiest clients before December 31. "We'll show them scenarios where they will benefit from a conversion and scenarios where they won't, to make sure they are comfortable they've made an informed decision," he says.

Advisors should explain to clients that a partial conversion mitigates tax risk, adds Ben Norquist, the CEO of Convergent Retirement Plan Solutions LLC, a Roth conversion software developer in Brainerd, Minn.

"We don't know what's going to happen with marginal tax rates," Norquist says. "Converting a portion of the IRA diversifies the tax risk."

It's urgent that advisors speak with clients before New Year's Eve because there's an option to report income from a 2010 conversion in 2011 and 2012 (half each year) instead of declaring it all this year. And so we have come full circle: back to the uncertainty surrounding the EGTRRA's sunset and future tax rates.

Fortunately, this decision need not be made until the client's 2010 return is filed and that could be as late as October 17, 2011, the extended due date for 2010 returns, says Tedone. If worse comes to worst and things are somehow still up in the air come April 15, Tedone plans to file extensions for his clients who converted and make sure they have paid the IRS as if the conversion will be reported in 2010, to avoid underpayment penalties.

Yet another option for handling a 2010 conversion is to forget it altogether by recharacterizing it by October 17, 2011.

New Benefit Plans For Small Businesses

If a successful business owner client wants to save more for retirement by putting aside more tax-deferred money than currently allowed (which is only $49,000 in 2010 for defined-contribution plans) he has a new option this year, the DB(k). This plan pairs a traditional defined-benefit pension with a 401(k) and is cheaper to administer than two separate plans.

Although this hybrid hasn't proved popular so far, "There are cases where it could work," says Jim Van Iwaarden, a Minneapolis consulting actuary and head of Van Iwaarden Associates. "It would be good for an employer that has been having trouble passing the non-discrimination tests for a 401(k) plan and who is concerned about administrative costs."

In addition to what a business owner defers through the 401(k) portion of the plan, he can get a pension for himself of whichever is less: either 1% of his average pay for every year he's in business, or 20% of his average salary during his five consecutive highest-earning years. But like any pension, the DB(k) requires the employer to contribute for workers, too, Van Iwaarden notes. Moreover, the company must match the contributions employees (including the owners themselves) make to the 401(k) plan, up to 2% of pay. So in the end, the DB(k) is most appropriate for profitable, established businesses with dependable cash flow.

And coming in 2011: SIMPLE cafeteria plans, for businesses with up to 100 workers. The only owners allowed to participate in these plans are C corporation shareholders. Still, "a SIMPLE cafeteria allows your key and highly compensated employees to maximize their benefits," says Jan LeTourneau, compliance manager with WageWorks, a San Mateo, Calif.-based benefits administrator. Moreover, the employer avoids payroll taxes on the wages that workers direct into the SIMPLE.

The primary advantage is the safe harbor from non-discrimination testing. These tests have historically prevented very small businesses from adopting cafeteria plans-say, a C corporation with four employees, two of whom are key or highly compensated-according to LeTourneau. To get the safe harbor, employers have to contribute for eligible employees, among other things. But there are different methods of calculating the employer's required contribution, and jumping from one method to another from year to year is permitted.

States Pursue Non-Residents, And Vice Versa

Now is a good time to discuss state-tax issues with clients who travel in their work, such as executives. Tedone says New York in particular has become aggressive in auditing non-residents. "If a client performs services on any day in a state, you need to determine whether he is required to file a return with that state," Tedone says.

Receipts for restaurants, hotels and tolls help document the client's whereabouts. "Also make sure clients record in their calendars where they are working, even if it's in their home office," says Tedone. He tells clients to print and file at home a copy of their Outlook calendar in case they change employers before the auditors call.

Some clients are taking the offensive and actively seeking out tax havens. One of Townsend's clients in the Tar Heel state is pondering whether to realize a large capital gain, so early in 2010 he decided to move to state-tax-free Florida, where he already had a home. "That way if we decide to trigger a capital gain late this year, not only will he get the 15% federal rate but he'll also avoid almost 8% in state tax," Townsend says.

Other clients may benefit from a chat about their state's rules regarding a change of domicile. Townsend says some folks think that all they need to shake loose of taxes in their old state is an Orlando P.O. box and a bright orange Gators sweatshirt announcing they're a Floridian.