You can’t confuse Delphi Greek restaurant with Smith & Wesson. Delphi specializes in kebabs and baklava -- not AR-15s and ammunition.

Yet the Los Angeles restaurant is one of about 3,100 U.S. businesses that still proudly stand with the National Rifle Association. At a time when major corporations like Delta Air Lines Inc. and Dick’s Sporting Goods Inc. are rethinking their relationship with firearms, the NRA’s legion of steadfast supporters in its Business Alliance provides a sharply different view of America’s enduring gun culture.

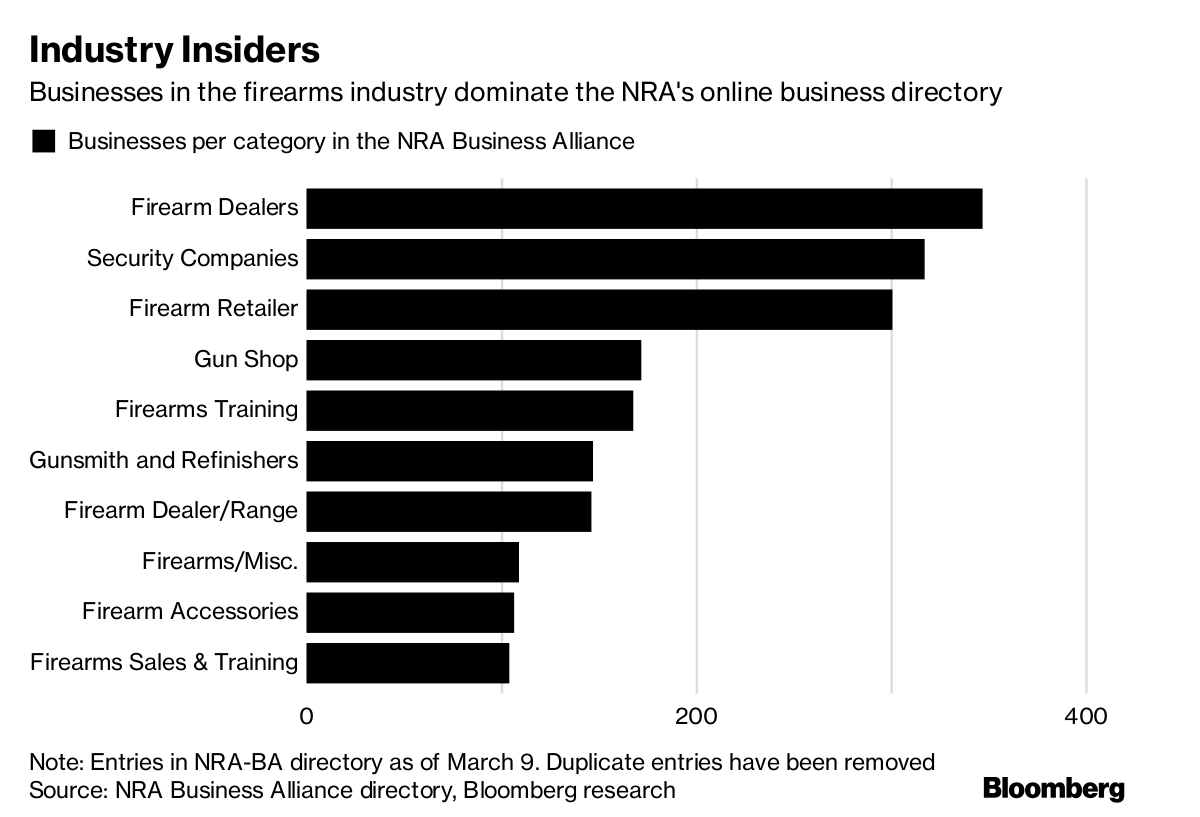

These outfits are the business equivalent of the NRA’s about 5 million claimed individual members. Most are small concerns. Many are associated with the firearms industry. And whether they’re in liberal bastions or the reddest of red states, they tend to oppose any tightening of gun controls, despite the national outcry over the Feb. 14 school shooting in Parkland, Florida.

The Business Alliance, as the group is known, has members in 50 states. They range from a pawnshop in Hartselle, Alabama, to a stone veneer contractor in Schuylkill Haven, Pennsylvania, to a hunting preserve in Kamuela, Hawaii. Businesses pay a yearly fee that members said can range from $40 to $150 per year, and in return they get visibility, a plaque and the chance to identify with a cause.

“The Second Amendment for me is very personal,” said Roozbeh Farahanipour, who owns Delphi and fled his native Iran after leading student protests in 1999. “As long as I think that they’re defending the Second Amendment, and it still is challenged by a group of people, I believe I need to support them.”

The NRA still wields political clout. But the quick erosion of support among America’s largest businesses reflects its changing place in the national landscape. An NPR/Ipsos poll taken two weeks after the Parkland shootings found just 36 percent of Americans said the NRA represents their views, down 7 percentage points from October.

Frontal Assault

After the Parkland shooting, businesses affiliated with the NRA came under pressure as never before, with protesters using Twitter and Facebook to threaten boycotts and students at the school upbraiding politicians for taking its money. Publicly traded companies almost uniformly dumped the organization, with the high-profile exception of shipping company FedEx Corp., ending special discounts for NRA members and removing their logos from the NRA’s website.

NRA spokesman Andrew Arulanandam didn’t respond to phone and email messages asking about the group’s relationships with business. But casual supporters with a broad clientele have peeled away, leaving niche concerns motivated by ideology.

Farahanipour’s restaurant is less noted for devotion to firearms than for fish tanks so splendid they have their own Facebook page. But the 46-year-old believes firearms could have swayed the outcome of his student rebellion against theocracy, and keeps two Glock handguns.

When Delphi’s tie to the NRA became known, Farahanipour endured reviews and social media posts criticizing his affiliation, but he was unmoved.

“I went through many worse things in my life to think that a couple of the comments or reviews, they can change my mind,” he said.

The same goes for Brady Phenicie, 52, who owns information technology company Phenicie Business Management in Healdsburg, California. He’s received calls from people upset over his affiliation and threatening to withhold business.

“I answer to myself,” Phenicie said. “My reason for joining is saying, ‘Hey, thank you for checking my rights, because I really feel like they’re going away.”’

The exodus at the national level marks a turning point for the NRA.

Dreamed up in 1871 by a pair of Union Army veterans, it largely promoted shooting sports and safety until the late 1960s and the rise of law-and-order politics. Today, the group has become a major player in accelerating political polarization. In the 2016 elections, the NRA gave 99 percent of its contributions to Republicans, according to the Center for Responsive Politics. In 1990, the GOP received just 65 percent.

Last Stand

As part of its turn rightward, the NRA has developed its own media profile led by spokeswoman Dana Loesch, who stars in videos that present an ominous view of an America engulfed in a barely contained conflict that threatens to explode into violence.

“They were a moderate group,” said Scott Melzer, a sociology professor at Michigan’s Albion College and the author of a book on gun politics. “I would characterize them as part of the mainstream American life.”

“Today’s NRA appeals primarily, almost solely, to diehard guns-rights enthusiasts.”

It was company that the Music Center, a Los Angeles organization that hosts ballet and classical-music concerts, was surprised to find out it kept. Howard Sherman, its chief operating officer, said few knew the center was a Business Alliance member until an attendee called.

“We had been signed up for the Business Alliance many, many years ago," Sherman said. “We would never take a political stand in that way.”

Fresh Resolve

Some relish the chance.

John Emerick, who owns JElectric Inc. in Hull, Iowa, paid for a five-year membership in the Business Alliance after the shooting. Chris Pastrana, who runs a media business in New Hampshire, also said he joined in the past few weeks, even though he doesn’t personally belong to the NRA.

Anthony Giura, whose western Pennsylvania waste management firm New Age Environmental Inc. is an alliance member, said the big companies have gone soft.

“These corporations are succumbing to political pressure, which I don’t think they need to do,” he said. “As far as me and my company, we’re not going anywhere.”

(Michael R. Bloomberg, founder of Bloomberg News parent Bloomberg LP, is a donor to groups that support gun control, including Everytown for Gun Safety.)

This article was provided by Bloomberg News.