The sharp decline of stocks in late 2018, followed by a strong surge at the beginning of 2019, has made for exciting investment watching. But more quietly, corporate bonds have seen some dramatic moves as well.

Late last year, investors sought to reduce risk by sprucing up the quality of their fixed-income portfolios. The move to securities rated “A” or better widened the spread in yield between the highest-rated corners of the corporate bond market and those with less-stellar credentials to levels not seen for several years.

As fears of inflation, trade disputes and interest rate hikes wore off, the selloff in late 2018 turned into a rally for credit markets at the beginning of this year, particularly among bonds with non-top-tier ratings. Investment-grade markets returned roughly mid-single digits in the first quarter alone. High yield did even better.

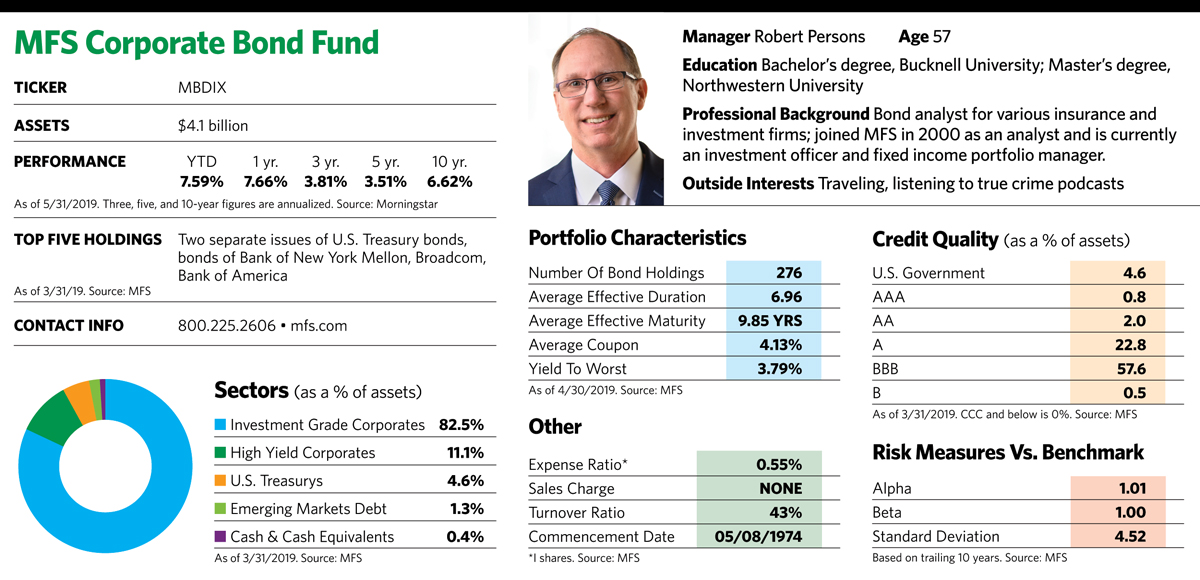

The $4.1 billion MFS Corporate Bond Fund benefited as investors decided to take a more “risk-on” stance in search of yield and gravitated to “BB” and “BBB” rated issuers, an area where the fund has a long history of being overweight relative to its benchmark, the Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Credit Bond Index. (“BBB” is the lowest investment-grade rating assigned by Standard & Poor’s, while “BB” is the highest non-investment-grade rating.) As of March 31, the MFS fund had nearly 70% of its assets in those two investment categories, with the lion’s share of that in “BBB” securities. Thanks largely to that positioning, the fund’s “I” shares outperformed the Bloomberg index during the first quarter of 2019, returning 5.60% while the index returned 4.87%.

But the big nod to mid-tier credits means the MFS fund may lag during less certain times when investors tend to seek out higher-rated securities in search of safety. That happened in 2018 when the fund’s performance fell behind that of two-thirds of its Morningstar peers. Nonetheless, the fund has generated strong returns over longer-term periods, with volatility similar to that of its benchmark.

That “up and comer” niche of the bond market has long been a favorite hunting ground for Robert Persons, who manages the fund with Alexander Mackey. Thirty years ago, when Persons began his career as an investment analyst, he noticed that he sometimes disagreed with the ratings that Moody’s or Standard & Poor’s assigned to some bonds. Many times, his assessment proved to be correct and the bonds were later upgraded.

“While rating agencies do a pretty good job, they often have trouble nailing down the differences between a ‘BB+’ and a ‘BBB-’ credit,” he says. “That difference is important, because when a bond moves from non-investment grade to investment grade, investors react favorably and its price goes up.”

Although the fund is classified as an investment-grade offering, Persons still has a particular fondness for what he views as the rising stars of the bond world whose ratings and valuations do not reflect their true quality. “We like to beat the rating agencies to the punch,” he says.

He looks to take advantage of persistent inefficiencies in the “BB” and “BBB” ratings universe by finding issuers that will likely enjoy capital appreciation with little incremental volatility over the index. Those inefficiencies are created when investors relying too heavily on ratings fail to identify undervalued, high-quality companies. The “BB” bond space is a good hunting ground for undervalued securities because their yields are often too low to attract high-yield investors. “It’s the most inefficient space in the bond market,” he says.

Over half of corporate debt today is rated “BBB,” making it the largest swath of the investment-grade market, whereas 20 years ago it accounted for less than one-third of investment-grade bonds. Investors must carefully navigate this vast territory to both home in on rising stars and avoid deteriorating “fallen angels” that might get downgraded or even go into default. Once a company drops out of investment-grade territory, Persons says, it’s a long, hard climb to get back in because rating agencies can be slow to recognize improvement.

Persons leans on a large staff of bond analysts to identify companies climbing the quality ladder. He also consults with MFS equity analysts to get a full picture of companies’ financial profiles and how bonds fit into them. “I prefer ‘BB’ companies where the stock price is improving to those with declining prices. I’ve found that a rising stock price is often a leading indicator for an improved rating.”

The fund spreads its bets widely among 279 holdings. One holding is Ball Corporation, a manufacturer of food and beverage containers and a company that Persons believes has a better financial profile than its rating suggests. The company is in a “consistently stable” industry and has strong cash flow, but its bonds have only a “BB+” rating, even though more highly leveraged beverage companies are in investment-grade territory. “I’m not sure why agencies have a more generous threshold for leverage for beverage companies than container companies,” Persons says. “They are very similar industries. I think the agencies have it wrong here.”

Persons also thinks MSCI, another “BB+” issuer, is an up-and-comer. The company has low capital requirements, stable cash flows from its analytics and index businesses, and minimal debt.

Fund holding Verisign, a domain name registrar, also has ample free cash flow to service debt, a consistent business and an equity stash that far outweighs its debt burden.

As far as sectors are concerned, Persons is not enthusiastic about consumer staples companies because he believes many of them have sacrificed growth to pay out the steady dividends they are known for. Changing consumer tastes, some ill-advised mergers and acquisitions, and increasing leverage are all making the sector a less defensive play than it used to be. He’s also wary of pharmaceutical companies because of government intervention and price controls in that industry. Instead, he favors health-care supply companies, which are positioned to take advantage of the aging population’s needs for products that require regular replacement for day-to-day caregiving.

The Cloud of Corporate Debt

The corporate bond market’s strong performance at the beginning of 2019 is unlikely to be repeated the rest of the year, Persons says. The MFS fund was up over 6% in the first four months alone.

Still, a lot of the elements are in place for a decent second half. The Federal Reserve seems happy to let interest rate hikes take a breather, at least for now. And while the stimulus of U.S. tax cuts seems to have run its course, expectations for modest growth and benign inflation bode well for corporate bonds. The outlook for U.S. investment-grade credit is favorable, and strong investor demand provides a tailwind.

One potential cloud on the horizon is the enormous amount of corporate debt floating around. According to the Fed, the dollar value of corporate bonds (excluding banks) outstanding in the U.S. grew from $2.2 trillion in 2008 to $5.7 trillion at the end of 2018. The bulk of this growth occurred in the investment-grade sector. Within that group, the most notable increase was in the “BBB” category, which more than tripled in value from approximately $0.8 trillion in 2008 to $2.7 trillion by the end of 2018. A substantial portion of the rise in corporate debt was used to fund share buybacks, dividends and merger activity.

Newer corporate bonds and loans have fewer stringent covenants than they did in the past. That reduces the protections for investors, says Robert Kaplan, president of the Dallas Federal Reserve. “In a downturn, some proportion of ‘BBB’ bonds may be at risk of being downgraded to less than investment grade,” he noted in a March report. “These downgrades, if they happen in sufficient size, could create dislocations for investors who tend to have specific allocations or restrictions based on credit-rating categories. These dislocations could further negatively impact credit spreads and market access for more highly indebted companies.”

Persons acknowledges that corporate debt is at an extraordinarily high level, especially for a period of economic expansion. But he believes the problem isn’t a systemic one, as it was in 2008. Many of the companies that have issued bonds since the financial crisis are in more defensive industries, such as technology. “In 2008, companies such as Microsoft, Intel and Apple had no debt. Now, they are big issuers in the market. No one seems worried about Apple’s ability to service its debt if a downturn occurs.”

The increase in debt is also spread out in a broader range of industries and companies than it was years ago. “A lot of different kinds of companies have taken on a little more debt,” Persons says. “That’s different than it was in 2008, when enormous leverage in the banking system froze the economy.” He adds that pension funds, insurance companies and other institutional investors with a mandate to invest in investment-grade securities support demand in the “BBB” market.

Still, some companies will be better prepared than others to weather an economic downturn. “That’s why investors need to be more vigilant than ever, which argues for active over passive investing,” says Persons.