Value investing, a bankable strategy for decades, has fallen on hard times. Value stocks have badly underperformed growth ones since around 2007, and the trend has accelerated in recent years. Disappointed value investors understandably want answers, and several popular and appealing explanations are making the rounds. The problem is they don’t quite stand up to scrutiny.

One theory is that value investing has become too popular. The discovery in the early 1990s that value had historically beaten growth is said to have triggered a stampede into value stocks that raised their prices and thereby doomed the strategy. It’s true that popularity can be lethal to any investing strategy — just ask hedge funds, or more recently, private equity. But has value been overrun with investors?

One way to find out is to break out the return from growth and value stocks into their three components: dividends, earnings growth and change in valuation. Companies supply the first two, and the last one is driven by demand for their stock. Isolating the change in valuation is therefore a window into what investors want.

Contrary to value’s supposed popularity, the numbers reveal that investors are more interested in growth. Since 1995, soon after value’s historical thumping of growth was documented and the earliest year for which earnings numbers are available, growth has beaten value by 1.6 percentage points a year through September, as measured by the Russell 1000 growth and value indexes. The sum of dividends and earnings growth was nearly identical for both, favoring growth by just 0.3 percentage points. The other 1.3 percentage points came from change in valuation, which shows that growth’s success was due mostly to greater demand for its stocks. If anything, in other words, it’s growth’s popularity that felled value.

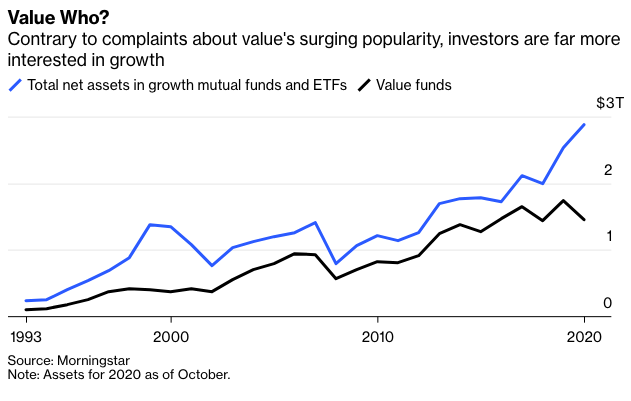

Those numbers jibe with the assets sitting in growth and value funds, which also belie the notion that value has surged in popularity. In 1993, U.S. growth funds managed $130 billion more than value ones, according to Morningstar, and more money has been invested in growth ever since. The difference is now bigger than ever. In October, growth funds oversaw a record $1.5 trillion more than value. If value is indeed more popular than growth, investors have a funny way of showing it.

Investors’ apparent preference for growth feeds a second theory, which is that low interest rates have juiced demand for growth stocks. The idea is that investors gauge the value of companies in part by discounting future cash flows. When interest rates decline, so does the discount rate, which makes future cash flows more valuable. And because, by definition, growth companies are expected to make more money, lower interest rates boost their valuations more than those of value companies.

It’s true that the valuation of growth stocks has swelled more than that of value since growth’s current win streak began around 2007. It’s also true that the 10-year Treasury yield fell from roughly 5% to around 1% during that time. But that’s just one period. Looking at all the available data, there appears to be little correlation between the movement of interest rates and the difference in valuation between growth and value stocks.

The correlation between 10-year Treasury yields and the difference in price-to-book ratio between growth and value has been a negative 0.14 since 1926, which is to say no discernible relationship. Using price-to-earnings ratio or price-to-cash-flow ratio, the correlation jumps modestly to a negative 0.33 since 1951, which is best described as a faint relationship. So changes in interest rates don’t appear to reliably inform how much more investors are willing to pay for growth than value. (A correlation of 1 implies that two variables move perfectly in the same direction, whereas a correlation of negative 1 implies that two variables move perfectly in the opposite direction.)

A third theory is that there’s nothing wrong with value investing; rather, it’s value investors who are broken. The purists, let’s call them, contend that buying a value index fund that slavishly picks stocks based on quantitative measures such as price-to-book or price-to-earnings ratios, as value investors are increasingly doing, isn’t value investing at all. Real value investors, they contend, research stocks exhaustively to find undervalued companies. Invariably, Warren Buffett, who famously pores over companies’ financial statements, is then paraded out as proof that true value investing works.

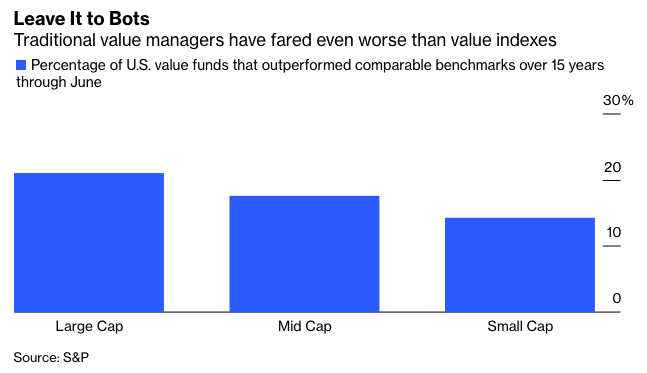

Leaving aside that Buffett is hardly representative of the average value investor, there’s more overlap between traditional methods of value investing and more recent, quantitative approaches than the purists let on. But even assuming the two play a completely different value game, there’s no indication the purists do it any better.

In fact, the numbers show that most of them fare worse. According to the latest SPIVA U.S. Scorecard, which tracks the performance of stock pickers relative to comparable indexes, 79% of large-cap value mutual funds failed to keep up with the S&P 500 Value Index over the last 15 years through June. Those targeting smaller companies made out even worse. Roughly 83% of mid-cap value managers and 86% of small-cap value managers lagged a comparable value index during the same period. As badly as value indexes lagged growth ones since the mid-2000s, traditional value managers fell even further behind. Not even the great Warren Buffett has kept up with growth stocks.

The last and perhaps most popular theory is that value companies are no match for competitors armed with superior technology. According to this view, growth stocks such as Amazon.com Inc., Netflix Inc., Microsoft Corp. and Tesla Inc. will continue to outshine value names such as Walmart Inc., Walt Disney Co., International Business Machines Corp. and Ford Motor Co. Indeed, fast-growing technology companies have dominated their industries so thoroughly in recent years that many people view their stocks as a sure bet.

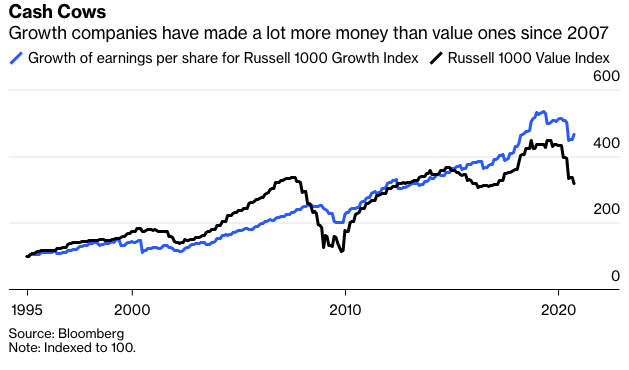

But don’t be so certain. Growth companies have outpaced value ones since 2007 by making more money and persuading investors to chase ever higher valuations. And they have made a lot more money. Russell 1000 growth companies increased earnings by 5.6% a year since 2007 through September, while value companies lost money, giving back 0.2% a year. That difference of 5.8 percentage points is the widest over comparable rolling periods going back to 1995, the longest period for which numbers are available.

It won’t be easy for growth companies to sustain that lead. The period since 2007 has featured an unusual group of high achievers that ballooned into the biggest cash cows in history. That includes Amazon, Facebook Inc. and Google parent Alphabet Inc., for starters, but also Apple Inc., with the rollout of its iPhone in 2007, and Microsoft, revitalized after its antitrust battles several years earlier. It’s unlikely that another group like them will come along soon. And given their gigantic size, it’s equally unlikely they can continue to grow at the same blistering pace.

They wouldn’t be the first to hit the proverbial growth wall. Successful companies routinely start with a burst of growth that eventually plateaus or even declines. When that happens, investors often rethink their lofty valuations, and there’s a lot of room for the valuation gap between growth and value to tighten. The price-to-earnings ratio of Russell 1000 growth companies, based on 12-month trailing earnings, grew by 4.6% a year since 2007 through September, compared with 2.9% for value companies. That difference, too, was never higher before May over comparable rolling periods.

In fact, there’s a long tradition of growth stocks failing to live up to impossible expectations. Every generation seems to learn that lesson anew. For boomers, it was the Nifty Fifty of the late 1960s and early 1970s. For Generation X, it was the internet companies of the late 1990s. And there are countless episodes before that. History doesn’t look kindly on the proposition that the latest batch of highfliers will sustain their spectacular success indefinitely.

Nir Kaissar is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering the markets. He is the founder of Unison Advisors, an asset management firm. He has worked as a lawyer at Sullivan & Cromwell and a consultant at Ernst & Young.