Leaving aside that Buffett is hardly representative of the average value investor, there’s more overlap between traditional methods of value investing and more recent, quantitative approaches than the purists let on. But even assuming the two play a completely different value game, there’s no indication the purists do it any better.

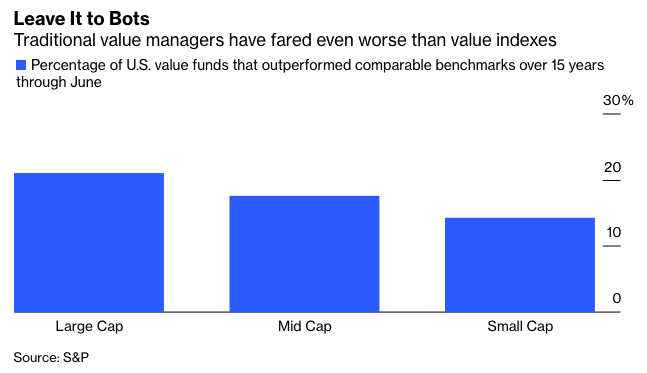

In fact, the numbers show that most of them fare worse. According to the latest SPIVA U.S. Scorecard, which tracks the performance of stock pickers relative to comparable indexes, 79% of large-cap value mutual funds failed to keep up with the S&P 500 Value Index over the last 15 years through June. Those targeting smaller companies made out even worse. Roughly 83% of mid-cap value managers and 86% of small-cap value managers lagged a comparable value index during the same period. As badly as value indexes lagged growth ones since the mid-2000s, traditional value managers fell even further behind. Not even the great Warren Buffett has kept up with growth stocks.

The last and perhaps most popular theory is that value companies are no match for competitors armed with superior technology. According to this view, growth stocks such as Amazon.com Inc., Netflix Inc., Microsoft Corp. and Tesla Inc. will continue to outshine value names such as Walmart Inc., Walt Disney Co., International Business Machines Corp. and Ford Motor Co. Indeed, fast-growing technology companies have dominated their industries so thoroughly in recent years that many people view their stocks as a sure bet.

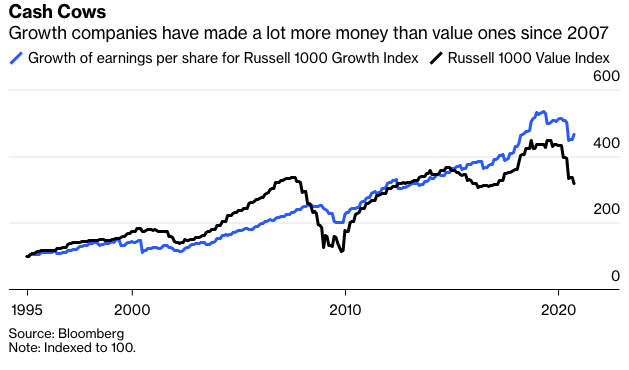

But don’t be so certain. Growth companies have outpaced value ones since 2007 by making more money and persuading investors to chase ever higher valuations. And they have made a lot more money. Russell 1000 growth companies increased earnings by 5.6% a year since 2007 through September, while value companies lost money, giving back 0.2% a year. That difference of 5.8 percentage points is the widest over comparable rolling periods going back to 1995, the longest period for which numbers are available.

It won’t be easy for growth companies to sustain that lead. The period since 2007 has featured an unusual group of high achievers that ballooned into the biggest cash cows in history. That includes Amazon, Facebook Inc. and Google parent Alphabet Inc., for starters, but also Apple Inc., with the rollout of its iPhone in 2007, and Microsoft, revitalized after its antitrust battles several years earlier. It’s unlikely that another group like them will come along soon. And given their gigantic size, it’s equally unlikely they can continue to grow at the same blistering pace.

They wouldn’t be the first to hit the proverbial growth wall. Successful companies routinely start with a burst of growth that eventually plateaus or even declines. When that happens, investors often rethink their lofty valuations, and there’s a lot of room for the valuation gap between growth and value to tighten. The price-to-earnings ratio of Russell 1000 growth companies, based on 12-month trailing earnings, grew by 4.6% a year since 2007 through September, compared with 2.9% for value companies. That difference, too, was never higher before May over comparable rolling periods.

In fact, there’s a long tradition of growth stocks failing to live up to impossible expectations. Every generation seems to learn that lesson anew. For boomers, it was the Nifty Fifty of the late 1960s and early 1970s. For Generation X, it was the internet companies of the late 1990s. And there are countless episodes before that. History doesn’t look kindly on the proposition that the latest batch of highfliers will sustain their spectacular success indefinitely.

Nir Kaissar is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering the markets. He is the founder of Unison Advisors, an asset management firm. He has worked as a lawyer at Sullivan & Cromwell and a consultant at Ernst & Young.