While funeral homes, medical professionals and accident lawyers may seem to have little in common, their businesses all benefit from bad news. The same can be said for managed futures managers, a niche of the investment world that few people understand, and others ignore or avoid.

Managed futures programs take long or short positions in futures contracts that usually cover four major asset classes: stocks, commodities, currencies and fixed income. Investors look for securities whose prices have risen or fallen, then take long or short positions to profit from what they hope will translate into longer-lasting pricing trends. Because these “momentum investors” use different methods for spotting and exploiting trends, their performances can vary widely. (For an explanation of the rationale behind momentum investing, see the box titled “The Human Side of Momentum Investing.”)

While managed futures programs can work as long as markets are in a trending pattern, either up or down, they are best known for their buck-the-crowd performance in prolonged equity bear markets. During those times, the short equity positions of managed futures strategies, as well as their ability to place long or short bets on other asset classes, work to their advantage.

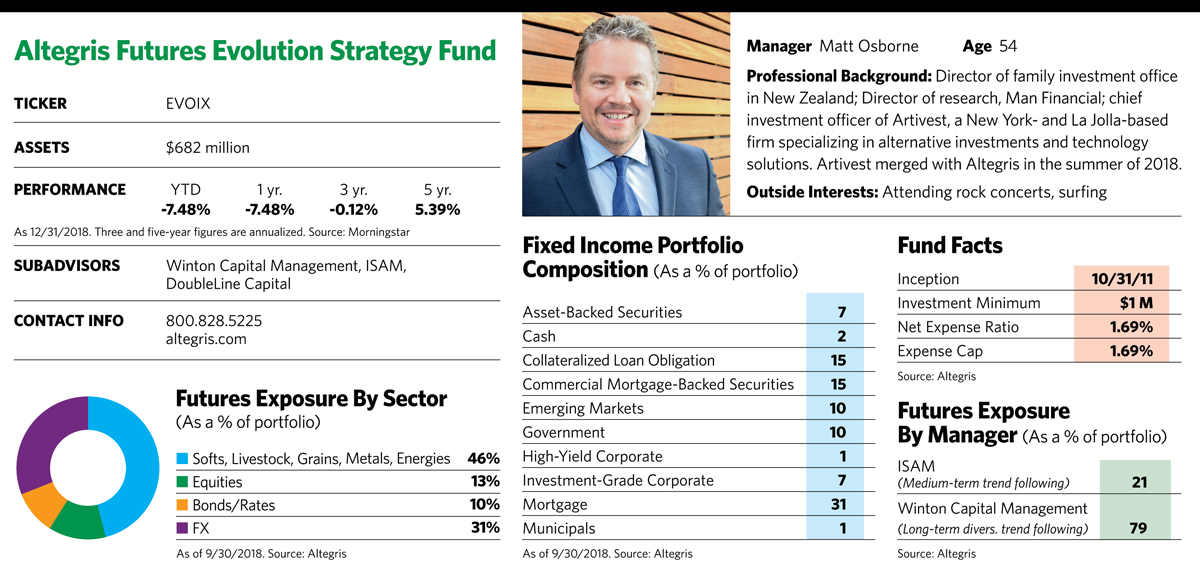

The $682 million Altegris Futures Evolution Strategy Fund (EVOIX) emphasizes that point in a chart that shows the superior performance of a managed futures benchmark against the S&P 500 during 11 separate quarters of equity market stress since 2000. These include the third quarter of 2008, when Lehman Brothers went bankrupt, the S&P 500 fell 22%, and the managed futures benchmark gained 12.7%. It also includes the third quarter of 2001, which saw the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and Pentagon and when the S&P 500 fell 14.7% while managed futures gained 3.9%. In the third quarter of 2011, the S&P 500 fell 13.9% while managed futures gained 2.4% in a period that saw the Greek credit downgrade and European sovereign debt crisis.

The problem for managed futures funds is that for most of the last several years the stock market has been on a fairly even keel, punctuated by short-term corrections and quick recoveries, and hasn’t demonstrated any of the longer-lasting trends that the managed futures funds thrive on. Commodities, currencies and fixed income have usually meandered or shown no clear direction.

“Persistent trends are the lifeblood of managed futures,” says Matt Osborne, chief investment officer of Artivest—the New York and La Jolla, Calif.-based alternative investments firm that merged with Altegris in the summer of 2018. “We haven’t experienced that environment in quite a while. The magic bullet is when at least two of the four asset classes we invest in are consistently trending. Instead, there has been a lot of sideways activity recently.”

The result has been disappointing performance for the group. The average fund in Morningstar’s managed futures category delivered a negative 1.22% annualized return over the three years ending December 31, 2018, and a 2.86% return over five years. The institutional class shares of the Altegris Futures Evolution Strategy, which is managed by three subadvisors Osborne selects and oversees, fell 0.12% over three years and saw a positive 5.39% return over five years.

Brighter Days Ahead?

Osborne believes that for managed futures investors, at least, brighter days could be on the horizon. Though he concedes they have underperformed in recent years, he also says “factors that have generally favored managed futures have also begun to strengthen recently. … These factors may signal a turning point for managed futures managers against a global and economic backdrop that more closely aligns with longer-term historical norms.”

With the era of quantitative easing by central banks coming to an end, fundamental and economic forces, rather than accommodative monetary policy, could drive the markets toward longer lasting, more pronounced trends. Periods of market volatility are lasting for longer periods than they have in the recent past, giving trend-based strategies a bit more room to run.

With their ability to sell bonds short, managed futures have generally performed well in prolonged rising interest rate environments, and Osborne thinks that the current period of increasing rates may follow that pattern. The Fed has signaled its intention to increase rates at least through the end of 2019, which may mean a sustained headwind for fixed-income markets and opportunities for short selling. At the same time, U.S. equities still carry extraordinarily high valuations and face threats from tariffs, trade wars and political discord. If those problems eventually settle into the stock market for more than a few weeks it would open up opportunities for profitable short selling.

Trends in other assets are also emerging. Despite widespread predictions it wouldn’t, the U.S. dollar strengthened against other currencies in 2018 and could continue to do so in 2019 if the U.S. economy remains strong. If it does, it could be profitable for investors to short foreign currencies and go long on the U.S. dollar. With the exception of oil, commodities have shown few trends, Osborne says. But that could change if investors perceive them as undervalued and their prices trend upward.

An Uphill Battle

Over the long term, managed futures portfolios tend to move independently of equities or bonds, and several studies document their value as a long-term diversifier with a very low correlation to stocks, bonds and other investments. These studies also show strong evidence that managed futures managers have been able to identify market downturns early on and take short positions, giving themselves an edge during times of extreme stock market stress. Osborne thinks investors should allocate in the neighborhood of 10% toward a managed futures investment if it is to have any real impact on portfolio returns.

But he cautions that investors need to have realistic expectations about what such funds can or can’t do. “Some people have been conditioned to expect that managed futures funds will always go up when the market goes down over short periods, and that is not always the case,” he says. “The fact is they have a zero correlation to equity markets, not a negative correlation.” It takes anywhere from a few weeks to a few months or more of a sustained trend before the benefits of any asset class play out, he says.

A common criticism of managed futures funds is their high costs. Investors in private funds specializing in managed futures typically pay a “2 and 20” fee structure (a 2% annual management fee and an additional fee of 20% on any profits). The fund fees are somewhat more palatable in the mutual fund world, though the cost of running the strategy and frequent trading makes the fees here higher than they are in the average equity fund.

The expense ratio for the Altegris Futures Evolution Strategy fund is 1.69% for institutional class shares, which require a minimum investment of $1 million. Management of the fund is split between three subadvisors. Winton Capital Management, a large managed futures specialist with $26 billion in assets under management, handles longer-term futures strategies using trend following and other investment strategies involving futures contracts. ISAM, a boutique alternative investment management firm with $3.5 billion in assets under management, focuses on medium-term futures strategies and is a more pure trend follower. DoubleLine Capital handles the bond portion of the fund, which is used to maximize returns on assets that aren’t being invested in futures contracts. Because futures contracts are highly leveraged, only about 20% of fund assets are actually invested in them at any one time.

In an era dominated by trendless and unpredictable markets, Altegris Futures Evolution Strategy and other managed futures funds have faced an uphill climb in the battle for investors, and several smaller funds have liquidated. Skeptics aren’t hard to find, either. In a report early last year, Morningstar analyst Tayfun Icten warned that the funds “can be highly vulnerable to a rapidly developing risk-off scenario, in which riskier assets such as equities sell off while bonds and the U.S. dollar rally.” If the markets remain range-bound and without clear direction, the funds could continue to struggle.

But Osborne thinks managed futures can be a useful diversifier for portfolios, and says that the environment in which they tend to do well is coming into clearer view. During short periods of recent market stress, such as the end of 2018, the funds as a group held up much better than the stock market.

“We’re finally moving to a place where global central banks are having less impact on the market,” he says. “This opens up more opportunity for trending markets to make a comeback. We believe that there is real potential for managed futures investors to once again see the benefits of active portfolio diversification.”