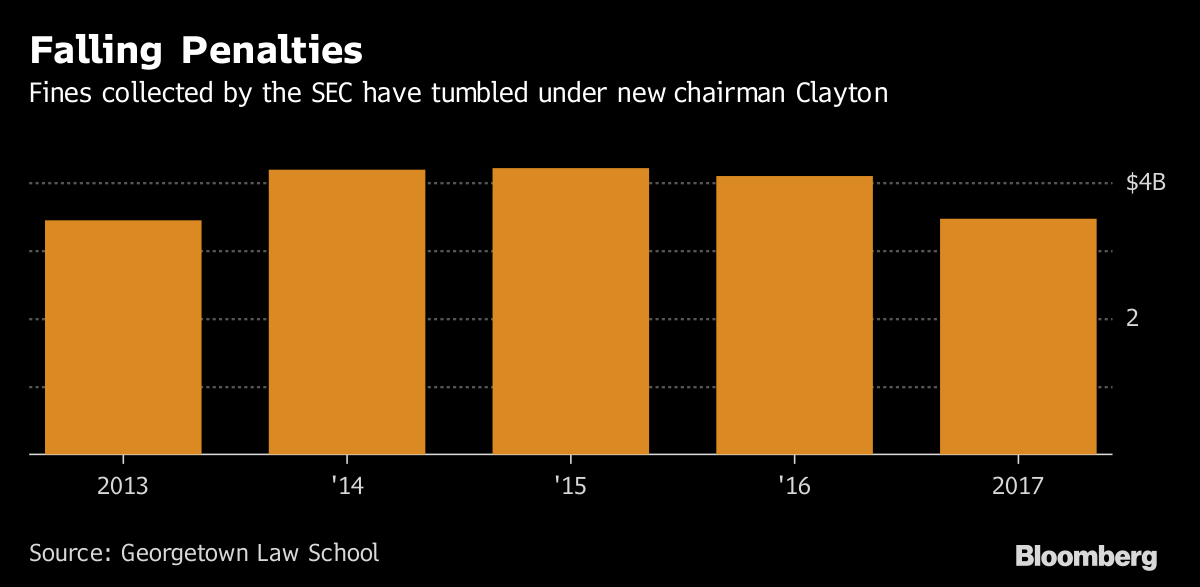

In its latest fiscal year, Wall Street’s top regulator sought the least amount of penalties since 2013, a drop that took place as it went months without permanent leadership and could show a softer approach to policing wrongdoing.

In lawsuits against companies and individuals, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission tried to obtain $3.4 billion in fines and disgorgement during the 12 months ended in September, according to data collected by Urska Velikonja, a law professor at Georgetown University. The agency filed 612 enforcement cases, also the fewest in four years, Velikonja’s research shows.

The time period includes former SEC Chair Mary Jo White’s final months at the agency, Commissioner Michael Piwowar’s brief stint leading it, and the first five months of new Chairman Jay Clayton’s tenure.

Although the data spans a transition atop the SEC, it may be early evidence that President Donald Trump’s more friendly tone toward corporations is having an impact on the regulator’s investigations into wrongdoing, according to Velikonja.

Big Firms

She points out that since Clayton -- the former Wall Street deals lawyer appointed by Trump -- took over in May, the agency has pursued just two sanctions against large financial firms: a $35 million settlement with State Street Corp. and a $97 million case against Barclays Plc.

In the same period a year earlier, more than a dozen big financial companies faced SEC sanctions, including Goldman Sachs Group Inc., Merrill Lynch & Co., UBS Group AG and hedge fund firm Och-Ziff Capital Management Group LLC, Velikonja said.

The overall decline in cases might show that the agency is shifting away from White’s so-called broken windows policy of aggressively pursuing smaller infractions to deter bigger violations, according to Velikonja.

“The big takeaway is that the sweeps are gone,” she said in an interview. “They’re not going after those technical violations.”

SEC spokeswoman Judy Burns didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment.

Hurting Shareholders

Not only did penalties go down in the aggregate for fiscal 2017 compared with the year earlier, but the median fine did as well, falling 35 percent, according to Velikonja’s analysis. She attributes that drop to the Republican view that corporate fines harm shareholders, who have often already been hurt when the allegations of wrongdoing drive down companies’ stock price.

For his part, Clayton has said the SEC won’t let up on enforcement under his watch and will be particularly focused on violations that impact mom-and-pop investors. There may also be other explanations for the drop in fines.

Cases brought by the SEC can often take years to develop, and agency leadership often strives to finish its most high-profile investigations as presidential administration’s draw to a close. Clayton’s enforcement team could now be in the position of rebuilding its pipeline of cases, with settlements against companies and individuals coming some time in the future.

For instance, in the first fiscal year of the Obama administration, the SEC sought $2.4 billion in penalties. In subsequent years, that number steadily rose as the agency pursued cases stemming from the 2008 financial crisis.

The regulator is also having to do more with less. Earlier this year, the agency cut back on non-essential travel, imposed a hiring freeze and curbed the use of outside contractors who assist SEC lawyers with cases. And until Clayton was confirmed, the SEC was down to two commissioners who voted on cases; one Republican and one Democrat. Without a tiebreaker vote, many cases were left in limbo for months.

— With assistance by Anders Melin.

This article was provided by Bloomberg News.