A few years ago, my boss came into our Monday morning staff meeting. He’s normally energetic, positive and funny, but on this day, he came in late and hunched over. He was sweaty, his color was off and he was moving slowly. He took his normal seat and said he just felt awful. Immediately, someone asked, “Do you have chest pain?” He said, “No, but my left hand is numb.” One person immediately recognized this as the warning sign of a heart attack and we took him to the ER.

A few years ago, my boss came into our Monday morning staff meeting. He’s normally energetic, positive and funny, but on this day, he came in late and hunched over. He was sweaty, his color was off and he was moving slowly. He took his normal seat and said he just felt awful. Immediately, someone asked, “Do you have chest pain?” He said, “No, but my left hand is numb.” One person immediately recognized this as the warning sign of a heart attack and we took him to the ER.

The ER has a triage system to separate the bumps and bruises from what’s truly life-threatening, and the moment he described his symptoms and the numbness in his hand, they immediately took him back to the treatment area. The rest of us went to the waiting room. Roughly an hour later, the doctor came out and told us that it was a good thing we brought him in that day. He was having a heart attack known as “the widowmaker.” Because we acted within an hour of symptom onset, his life would be saved. This window of time is known as the “golden hour.”

What if we told you that the research shows there is a serious, even life-threatening, illness in virtually all advisors’ practices—when top clients consider leaving. And worse still, unlike a heart attack, it has no warning sign. An ACAT is all too often the first symptom. That’s the bad news.

Here’s the good news. It turns out that there is also a “golden hour” in financial services during which the client relationship can also be saved—that is, if the right amount of aid and, just as important, the right type of aid is administered.

In our surveys, financial advisors say that acquiring new clients tops their list of concerns. There is no question that getting high-quality new clients is one of their most difficult jobs. Most of them only add about two new high-quality clients each year. Part of the reason this number is so low is that client defections cause us to start efforts at growth in deficit territory. But it doesn’t have to be that way. As we will see, there is a systematic process you can use to accelerate growth by stopping client defections.

Anchor Clients

Most every financial advisory practice has a number of key clients that by far represent most of the revenue. We will refer to these critically important people as “anchor clients.”

When we ask financial advisors to name their No. 1 client, with only rare exceptions do they have a problem answering. When asked who their No. 20 client is, some of them struggle to come up with the name. When we ask them about client No. 43, however, almost all of them have problems. While it may seem arbitrary to cite 43 clients, there is an important reason.

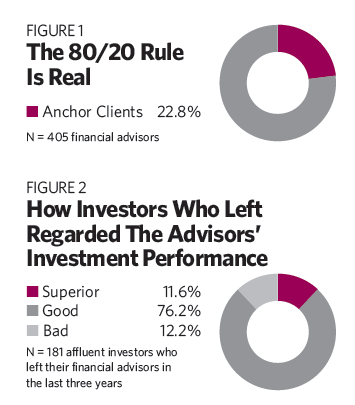

In a survey of 405 financial advisors, the average practice had 189 clients or households—43 of which were considered “anchor” clients. We asked them: “How many of your investment clients are very important, if not critical, to the success of your practice?” They responded (on average) 43, which is 22.8% of their entire clientele (Exhibit 1). This finding aligns with the Pareto principle, the classic rule that 20% of the input gets you 80% of the result.

Logically, financial advisors would want to keep all of this group. Since anchor clients are core to a practice, it would make sense to spend the most time with them and keep them satisfied.

How To Lose Anchor Clients

Investment management might be a core service offered by financial planners, but investment performance is not the reason clients stay. In fact, in one survey, nearly nine out of 10 clients who had left their advisors within the last three years said their investment performance was actually good or even superior.

We looked closer at how these clients were being treated.

We found that the top 10 anchor clients generally got a lot of attention. But beyond those, the attention the rest got tended to drop off rather quickly and was more randomly distributed. Many of them were subject to chronic neglect. Of course, the top 10 anchor clients matter, but so do numbers 11 and 43.

Very often, financial advisors have a false sense of security that if their best clients are not calling in and investment performance is at least pretty good, then everything must be going well. And as we will see, that is not necessarily the case.

Another interesting finding is that about three out of five advisors recognize they spend most of their time on non-anchor clients. This creates an unfortunate scenario in which they could lose their best ones.

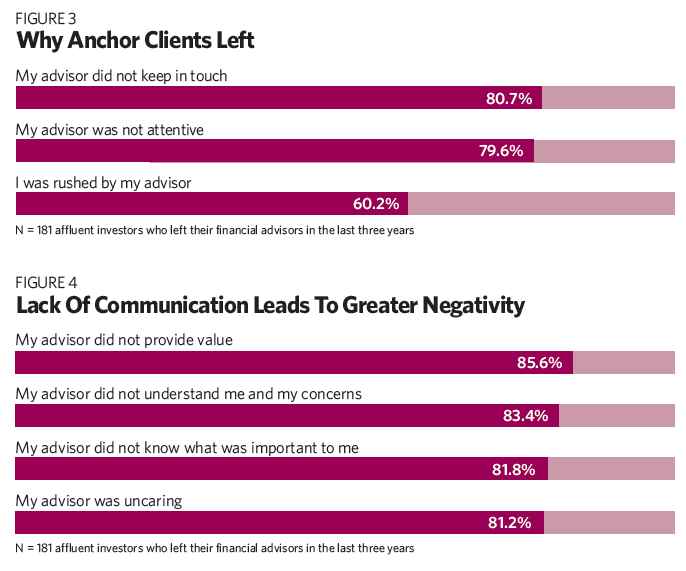

As Exhibit 3 shows, anchor clients who leave have different reasons for doing so, but one is that they are clearly not getting the level of attention they want. If an advisor starts to lose an anchor client, unless he or she takes corrective action, the bad feelings intensify (Exhibit 4).

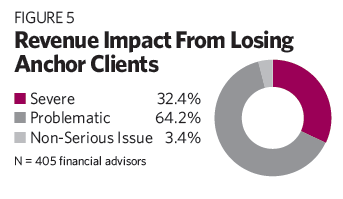

Clearly, if advisors don’t communicate in the ways anchor clients want, it becomes more likely the clients will leave. This can have very serious repercussions. On average, almost three-quarters of advisors lose one anchor client per year, and this is a serious hit to their revenues (Exhibit 5). Clearly, silence can be deadly.

Once a client has decided to leave, however, financial advisors have time to repair the relationship. For example, it will take about 60% of the clients nine months or more before they actually walk out the door. If the right amount of communication (and the right type) is offered, these “at risk” clients can be recovered.

All Communication Is Not Equal

Interactive communication makes an impact. In other words, an interpersonal interaction between advisor and client. Not mass e-mails. Not newsletters. Not Facebook posts. The advisor must reach out to these clients individually. The more it resembles a conversation, the better. In fact, just four such contacts per year resulted in 0.0% client loss. Think about that. Just one personal interaction per quarter can cure anchor client loss!

The foundation of that strategy is, of course, the annual client review meeting. Where we found advisors struggled the most was on how to prepare for and execute what are commonly referred to as “client check-in calls.” There is an art and science to making these effective. If all we do is check in, clients rapidly check out.

We found, instead, that we could create significantly greater impact in these calls if we follow a three-step process:

1. Demonstrating personal knowledge

2. Monitoring for change

3. Setting follow-up expectations

It’s generally thought of as a bad thing when a client is concerned about something, but what if we are wrong about that? What if their concerns are really a form of alchemy that gives us the chance to convert lead into gold—to change their problems into lasting, client value, at least if we have the courage to harvest them?

Too few advisors do this because when they hear about a concern they assume they have failed.

However, healthy practices harvest concerns. Advisors know that if they pursue these concerns, it shows they care. If problems are identified early, they can be solved more easily, before they become client-killers. Even if clients don’t have any issues, they feel respected and valued when you ask.

Here are three guidelines on harvesting concerns:

1. Ask In Person: Harvest concerns in person or on the phone—at the tail end of a conversation, which tends to work best as a productive capstone.

2. Operate From A Place Of Humility: Don’t operate from a presumption of “Aren’t we awesome?” and “We want to become awesomer.” We aren’t fishing for compliments; we are checking for concerns so that we can fix them.

3. Keep It Simple And Brief: Construct a simple sentence that directly asks the question. For example, “Is there anything that you were dissatisfied with or where we simply could have done better?”

For the great majority of financial advisors, keeping their top clients is essential to the ongoing success of their practices. But a substantial number of advisors are not taking the actions needed to ensure their anchor clients stay with them.

By identifying and effectively communicating with these clients, advisors can ensure the foundations of their practices remain in place.

Russ Alan Prince is president of R.A. Prince & Associates.

Brett Van Bortel is director of consulting services for Invesco Consulting.