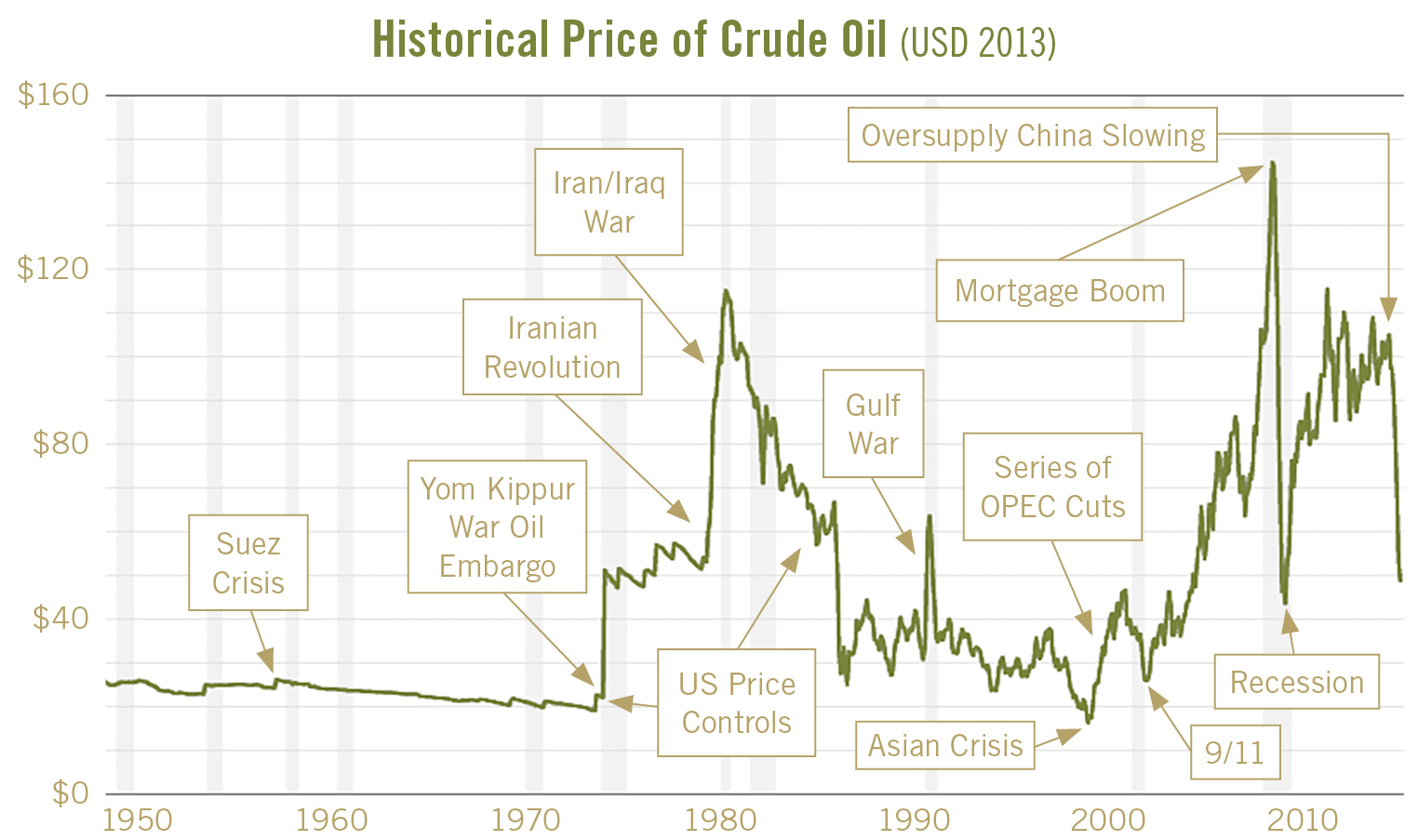

A month ago, on Thanksgiving Day, much to the surprise and dismay of global oil producers, drill equipment manufacturers and oil stock investors (among others), the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), decided to maintain rather than reduce its target production quota of 30 million barrels per day. In addition, Saudi Arabian oil minister Ali al-Naimi said, “it is not in the interest of OPEC producers to cut their production, whatever the price is. Whether it goes down to $20, $40, $50 or $60, it is irrelevant.” Commodities markets clearly expected a much more accommodative response to already weak crude prices; at minimum, a half million barrel per day reduction was priced into the November 27 meeting. The response was swift and punishing. In the following 2½ weeks, crude fell 25 percent from the mid $70s to $53 per barrel today — 50 percent below June’s $110 peak. This year’s downdraft is not unprecedented: The crude oil cycle regularly experiences wide price swings in times of shortage, oversupply or exogenous events such as war or natural catastrophe. The duration and magnitude of the price cycle is an imperfect function of global oil policy response and market expectations for price mean reversion. It seems unlikely the price of crude will stay in a narrow $50-$60 range in 2015, which seems to be consensus among economists. U.S. shale oil production from fracking and recovering Libyan shipments might easily be offset by economic turmoil in Russia or Venezuela or a reversal in OPEC production strategy.

A month ago, on Thanksgiving Day, much to the surprise and dismay of global oil producers, drill equipment manufacturers and oil stock investors (among others), the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), decided to maintain rather than reduce its target production quota of 30 million barrels per day. In addition, Saudi Arabian oil minister Ali al-Naimi said, “it is not in the interest of OPEC producers to cut their production, whatever the price is. Whether it goes down to $20, $40, $50 or $60, it is irrelevant.” Commodities markets clearly expected a much more accommodative response to already weak crude prices; at minimum, a half million barrel per day reduction was priced into the November 27 meeting. The response was swift and punishing. In the following 2½ weeks, crude fell 25 percent from the mid $70s to $53 per barrel today — 50 percent below June’s $110 peak. This year’s downdraft is not unprecedented: The crude oil cycle regularly experiences wide price swings in times of shortage, oversupply or exogenous events such as war or natural catastrophe. The duration and magnitude of the price cycle is an imperfect function of global oil policy response and market expectations for price mean reversion. It seems unlikely the price of crude will stay in a narrow $50-$60 range in 2015, which seems to be consensus among economists. U.S. shale oil production from fracking and recovering Libyan shipments might easily be offset by economic turmoil in Russia or Venezuela or a reversal in OPEC production strategy.

Throughout most of the 20th century, the price of U.S. petroleum was heavily regulated through production or price controls. From post World War II to the early 1970’s, crude prices ranged from $17 to $19 per barrel in 2013 dollars. However, the Yom Kippur War, begun in October 1973 with an attack on Israel by Syria and Egypt, changed the global petroleum landscape. Several Arab exporting nations imposed an oil embargo on the countries supporting Israel, including the U.S. By the end of 1974, 7 percent of free world production had been curtailed and the price of oil had quadrupled. Since then, the price of crude has proven both volatile and highly unpredictable, as modest changes in supply or demand realities, or expectations, holds substantial sway over the short term direction of oil prices.

Despite the new energy paradigm since the 1970s, there have been only a handful of times in the last four decades where the price of oil has fallen as much as it has in the last six months.

1986

The year 1986 witnessed one of the most dramatic waterfall declines in oil price history, stemming from a combination of Saudi policy reversals and derivatives on oil futures. From 1980 to 1986, crude prices fell as demand shrunk due to structural/behavioral declines in oil usage stemming from the 1970s oil shock and lower consumption during the 1979-1982 recession. Simultaneously, non-OPEC exploration and production, driven by tantalizingly high oil prices in the late 1970s, increased output by more than 6 million barrels per day. OPEC was facing lower demand from non-OPEC nations who sought greater energy independence. In response, from 1982 to 1985, OPEC attempted to set production quotas for its members low enough to stabilize prices. But OPEC members repeatedly cheated and produced beyond their allotment, leaving Saudi Arabia to act as the swing producer to stem the freefall in prices. Tired of losing money and market share at the expense of the rest of OPEC, in August 1985, the Saudis linked their oil price to the spot price and increased production from two to five million barrels per day. Oil prices fell 60 percent in eight months and stayed relatively stable until the Gulf War in 1990.

A foreshadowing of the damage that can be caused by greed, regulatory loopholes and leverage (harken back to the 2007-8 mortgage crisis, magnified by the plethora of levered mortgage backed securities), the 1985-1986 oil price decline was probably amplified by the unwinding of energy-based tax shelters. The highest marginal personal tax rate was 50 percent to 70 percent in the 80s; thus, many wealthy people put their money into energy-backed tax shelters designed to produce tax write offs. 1986 was a perfect storm of burgeoning crude supply and tax reform which lowered marginal rates and disallowed windfall profit tax and other tax deductions. The rapid unwinding of tax shelters likely exacerbated oil’s decline and could have provided a lesson to regulators regarding speculation and leverage in asset backed securities.

1998

From 1990 to 1997, world oil consumption increased 6.2 million barrels per day according to the WRTG, driven primarily by the booming Asia Pacific region. Hoping to capitalize on Russian production declines and most likely underestimating the massive overinvestment in Asia, OPEC increased its production quota by 10 percent in late 1997. For a variety of reasons, the explosive growth in emerging markets came to a standstill in 1998; the price of oil plunged 50 percent, numerous currency shocks threatened financial contagion and (once again) unregulated, levered currency derivatives imperiled the US financial system, culminating in the high profile government sponsored bailout of hedge fund Long Term

Capital Management. OPEC responded rapidly by cutting production three times, alleviating price pressure.

2008

In late 2006, OPEC began reducing production due to its concern with growing crude and petroleum products inventories. This, in conjunction with accelerating demand from an increasingly prosperous China, and the proliferation of petroleum backed derivatives, drove oil prices to a record $145 on July 3, 2008. By December, as the credit bubble burst, oil touched $40 a barrel; many nations, including the US, were concerned with financial system survival. Production cuts abounded in 2009 and oil recovered in a V shaped pattern. Price momentum continued in the face of the Libyan civil war in 2011 and stayed above $80 per barrel for four consecutive years until the fall of 2014.

2014

Complacency was probably at its height mid-year. There were few market pundits predicting the 50 percent decline in crude in the last several months. But unusually acerbic rhetoric from Saudi Arabia’s oil minister in the last several weeks regarding their posture on maintaining market share at any cost shocked the market. The outcome of a strategy focused on production ramp in a falling price environment almost always results in a protracted cycle of price and political destabilization. Some speculate OPEC’s tactics could have been political. The Saudis could be taking punitive measures against the US for the substantial incremental supply that unconventional drilling (fracking) has created in recent years, making the US and the rest of the world less dependent on OPEC oil supplies. Or they could be punishing Russia for dissension in the quota creation process. As the second largest and one of the higher cost oil producers/exporters globally, Russia is particularly vulnerable to falling crude prices. The last several months’ price action has severely destabilized the ruble, forcing the State Duma to pass emergency legislation and nearly double borrowing rates to thwart a run on the Russian currency and banking system. Perhaps OPEC’s strategy is to regain market share by sending sizeable but vulnerable producers like Russia

and Venezuela into an economic and financial tailspin.

OPEC’s decision to maintain current production may have been a catalyst for oil’s most recent downdraft, but subtle changes in the supply/demand curve in the last year set the stage for the rout. In the last year or two, Europe’s stagnant and China’s slowing economies have weighed on demand for oil. Simultaneously, marginal supply growth from US fracking and an unanticipated rebound in Libyan supply have created excess stores of crude. The supply/demand curve is price-inelastic, meaning a relatively small change in production or consumption has an outsized impact on price. Since there are no readily available substitutes for oil in the short run, a spike in the price of oil does not reduce levels of consumption significantly. Airlines still fly and people still drive their cars, though they may grumble more. Conversely, if crude prices decline, people don’t automatically consume more. Supply is also slow to adjust. Oil exploration and production involves long lead time projects with fixed costs and debt obligations.

Most global pricing dislocations are either event driven (war, supply disruption) or reflect a slow build of evidence capped by a catalyst that drive the direction and probability of price movement. Thus most recently, a bit more shale oil and a marginally lower China GDP, combined with pessimistic comments from the Saudis, shifted sentiment from complacency mid-year, to caution in the early fall, to panic most recently. Shadow leverage from commodity-backed derivatives probably magnified the downdraft. However, one should not get too used to cheaper oil. In the long run, low oil prices erode the conditions that bring them on. Cheap oil stimulates the economy resulting in increased energy use. The windfall to consumers tends to be short lived. Volatility is here to stay and the ability to drive or predict oil prices in the short term is all but impossible. At this point, the least popular crude scenario in 2015 is a return to $100 plus prices; economist consensus is for stable to lower prices in the coming year, as the path of least resistance is extrapolating the current environment. Given the strength in the US economy, continued low interest rates, broad access to capital and more conservative than forecasted crude capital expenditures, we would not be surprised to see oil prices significantly higher as the year progresses.

Marian Kessler joined Becker Capital in 2004. She has more than 20 years of experience in the investment business as an analyst, portfolio manager and managing director of IDS/American Express, Safeco Asset Management and Crabbe Huson.