After 13 years of a near-vertical updraft for financial assets, there’s a generation of financial advisors who have never had to explain sequence-of-returns risk to their clients, much less help them make some hard choices about retirement they may never have expected to make.

These advisors are what Catelyn Stark from Game of Thrones would call “the knights of summer.” And winter is coming.

Even Professor Google is underprepared: A search for information about inflation risk yielded 650,000 returns. Longevity risk, 425,000. Duration risk, 113,000. Sequence risk? 32,800.

“The last decade hasn’t done us any favors in this regard,” says Jamie Hopkins, a managing partner of wealth solutions at Carson Group in Omaha, Neb., and a specialist in retirement income planning.

The onset of high inflation for the first time in 40 years triggered a cascade of market events this year, derailing the powerful long-term trends in stock and bond prices. Between January 1, 2009, and September 15, 2022, the Standard & Poor’s 500 produced annualized returns of 13.61%, even after factoring in this year’s nasty bear market (the S&P 500 fell 17.26% for the year through September 15). Bonds, often viewed as a safe haven in bear markets, also succumbed to inflation—the Bloomberg Barclays Aggregate Bond Index fell 12.07% this year through September 15, leaving investors with nowhere to hide.

“All of those first risks fall to the core of investment management strategies,” Hopkins says. “You handle them for all of your clients. Inflation is important for a 22-year-old and an 85-year-old. The challenge with something like sequence risk is that it impacts a much smaller group of clients for maybe three to five years at the beginning of retirement, but it can destroy them on the back end.”

In layman’s terms, sequence-of-returns risk, or sequence risk, is the danger that a market downturn might coincide with a retiree’s first withdrawals from a portfolio, and that those withdrawals will significantly compromise the portfolio’s ability to last through retirement. In 1994, William Bengen authored an article in the Journal of Financial Planning that conceived the popular so-called “4% rule,” which was actually 4.5% in his paper.

Bengen examined how new retirees fared if they started making withdrawals in a variety of historical market scenarios. He found that investors would not outlive their money if they used a 4.5% withdrawal rate from a portfolio evenly divided between stocks and bonds. However, market developments of the past year have prompted a serious reappraisal. Some like Christine Benz, Morningstar’s director of research, advise today’s retirees to lower their withdrawal rates to 3% of their assets, no easy feat for many. Bengen himself has written in Financial Advisor that there is no reason why 4.5%, or any number, should be set in stone.

Sequence-of-returns is still a relatively new concept in the financial advisory glossary. And it took a long time before the financial services industry—so heavily focused on accumulation—took sequence risk seriously enough to develop strategies for mitigating it.

“The retirement income arena inside the financial services industry is only about 20 years old,” Hopkins says. “I started in 2010, and it was not part of the CFP curriculum. It wasn’t until 2016 that the [CFP Board] added retirement income. This is a competency that’s existed only for a few years, and that’s the gold standard of education.”

The reason for the failure of the financial services industry to tackle sequence risk, he says, comes down to the simplest issue: money. “Most of the industry isn’t compensated for managing that risk,” Hopkins says. “In the grand scheme of the industry, it’s not worth it.”

Anthea Perkinson, the founder and principal of Monterey Associates in Pelham, N.Y., agrees.

“That’s exactly right. The average advisor is very conversant in investments and investment returns, less conversant in tax planning, and even less when dealing with clients who go from relying on a paycheck to relying on a portfolio,” she says. “And it’s part of the reason I’m fee-based, and hourly for the most part. My income is not based on assets, where all my attention would go to accumulation.”

The Cost Of Retiring In The Wrong Year

Sequence risk might be short-lived, but it can have long-term implications. To help investors see how it works, a team of researchers at Vanguard Group has published two reports that look at how the problem may play out for today’s retirees.

The first, called “Safeguarding Retirement In A Bear Market,” was released in June 2020 and examined the effect of sequence risk on retirees who depend on a financial portfolio to generate income. Authors Kevin I. Khang and Andrew S. Clarke began their research in 2008 during the global financial crisis and were prompted by the pandemic to release their findings.

“At the start of 2020, we wanted to add more precision to our thinking on the topic of managing sequence risk in the face of bear markets. The Covid-related market selloff hit shortly after, and it sharpened our focus on the topic,” Khang says in an email interview. “We aimed to understand what happened in past bear markets and recessions, assess how big of a difference adverse sequence risk could make in retirees’ well-being, and use that to inform what may be actionable for today’s retirees.”

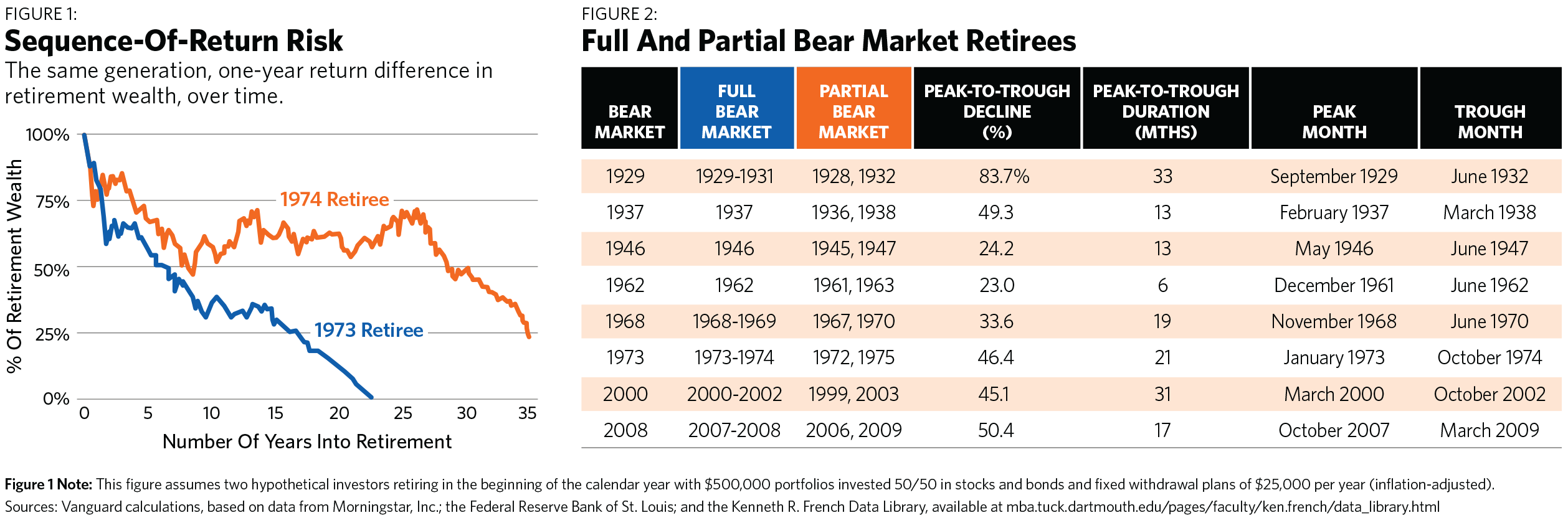

And so the researchers examined what happened to people who retired during or near six major U.S. bear markets since 1926 and compared them to those who retired in bull markets. Their findings were brutal.

Those unlucky retirees who suffered a poor succession of returns—only because of the timing of their retirement—were 31% more likely to outlive their wealth, had 11% lower retirement income streams and left 37% smaller bequests.

“Every withdrawal turns a negative return, which is temporary in nature, into a permanent impairment of the balance,” the Vanguard team wrote. “The amount withdrawn at a considerable loss reduces the opportunity to recover over the long term. Because the opportunity cost of withdrawing a dollar—measured in the expected return on the dollar until the end of retirement—is particularly high immediately after sequence-of-return risk strikes, the ‘magic’ of compounding return works against the retirees who must do so.”

As an example, they took two hypothetical retirees, one retiring in 1973 and one in 1974. The researchers assumed that, at retirement, the investors’ total wealth was held in balanced portfolios, evenly split between stocks and bonds and rebalanced monthly, and that the portfolios were the retirees’ sole income source for 35 years of retirement. Both employees entered retirement with $500,000 and planned to withdraw $25,000 per year (5%), adjusted for inflation—higher than the popular 4% rule of thumb, but more in line with what advisors tend to see among clients.

The only difference between 1973’s retiree and 1974’s was in their start and end dates, giving them 33 overlapping years. In fact, their long-term returns in the absence of withdrawals were very comparable—5.23% for 1973’s retiree and 5.1% for 1974’s.

Factoring in withdrawals, however, they experienced dramatically different outcomes.

The researchers found that the 1973 retiree, who left work in a severe bear market decline, would have run out of money after just 23 years in retirement. By postponing retirement just one year, however, 1974’s retiree—who left work at the tail end of the bear market—would have maintained a balance of roughly $300,000 for most of the 35 years, and was able to leave a bequest of about $125,000.

Clients Are Listening To Tough Truths

Before entering financial services, Lucas Minton, a dually registered investment advisor and founder of Minton Wealth Strategies in Cabot, Ark., says he worked with a “quasi-state organization” that was involved in Medicaid processing.

“When you work with Medicaid, you see a lot of retirements that go off the rails,” he says. “Those situations are incredibly painful to see, and keeping retirements and legacies from going off the rails is something I’m very passionate about.”

Minton says his early days in the industry coincided with the financial crisis, which he describes as one of those defining events where one remembers everything leading up to it and everything that happened after. “If someone had retired in that time frame, they were probably back to work by 2012,” he says. “We spend decades worrying about returns, and of course that’s important. But mitigating risk is just as important, and it’s never really talked about. Over the last few years, I’ve felt like I was John the Baptist preaching in the wilderness, and no one’s listening.

“Well, now they’re listening,” he continues. “Above all, I tell them, they can’t take on more risk to support an income level. At some point they might have to adjust their income down to make it last.”

Like Minton, Perkinson says she’s been talking with clients about the concrete realities of retiring in a down market since the spring, using actual dollars, not percentages, “because people can understand the dollars.”

“During regular markets, you’ll have $10,000 a month, but if the market goes down to X, you’ll get $7,000. Can you live on that?” she asks.

So far, the short answer has been yes, she says, even for clients who initially doubt it. Many of them, after all, have done it recently.

“We talk about what they did during the pandemic when they stopped spending money in April 2020 because they didn’t know what would happen. They know they can live on spending less,” she says. “And if they still don’t believe me, I tell them to go back and look at their bank statement for April 2020 and then compare that to August 2020.”

Sequence Risk Strategies

But there are other things experts can do with clients before curtailing spending. The first and most obvious possible tweak to a client’s retirement plan is to look for flexibility in the retirement date.

Hopkins says that by pushing back the date, even by just a year, clients will continue earning income as opposed to spending down assets, and they’ll be starting retirement closer to the next bull market. They’ll also need one less year’s worth of assets.

“We’re not talking by five years. Even just six months could make a difference with sequence risk,” he says.

Granted, not all clients will be able to do that, he admits. Their health might force them to retire anyway. And if there’s a recession, they might lose their job and not have another one to jump to. But even then, there are good strategies to avoid sequence risk.

One is to look at the investment allocation leading up to and following a retirement date. “The three years leading into and the three years after retirement should be the most conservative of your investment life,” Hopkins says. “That way you’re preserving your assets at the most critical time.”

After that, clients can return to either a steady equity glide path—or even take a counterintuitive rising glide path to ensure future growth. If they need additional income in those three years after they leave work, their advisors should help them plan for alternative sources to use as a bridge: borrowing against a life insurance policy, for example, or even taking out a home equity loan, he says.

“I’m not saying borrow for three to five years. Just know that if the market drops you can pull from somewhere besides your equities,” Hopkins says. “Use those as the spending mechanism for the down market.”

At Sensible Money in Scottsdale, Ariz., founder and retirement planner Dana Anspach takes a page from pension plans. “We look at building a portfolio much like they do. They have to deliver monthly checks, and we have to deliver monthly checks,” she says. “So we’re going to need a portfolio structure that’s basically an all-terrain investment vehicle.”

That means using equities for long-term growth and bonds to cover cash flow, Anspach says, adding that she does not want her clients relying on dividends for income. Ideally, she’ll start working with a client 10 years before they retire so she can effectively ladder bond maturities to create income for each year of retirement.

“We hold to maturity, so we’re not concerned with fluctuation in bond prices,” she says. “This is very different from what people might do in the accumulation phase. In the accumulation phase, it’s all about opportunities. You can always buy something new without disrupting what you already hold.”

She takes herself as an example: At 51, Anspach says she’s 100% in equities and plans to stay there until she’s 55. At that point, she’ll shift a portion to a bond set to mature when she’s 65. This strategy also allows her to skip a really bad market year if necessary.

“If you start 10 years out, and that’s a down year, then wait a year,” she counsels. “The reality is that most people show up between one and five years prior to retirement, and these options aren’t available in the same way.”

The Right Way To Tinker With Withdrawals

At some point, advisors and clients may run out of pain-free solutions to sequence risk mitigation, and the time will come to address a retiree’s withdrawal rate. Spoiler alert: A reduction in withdrawals doesn’t have to be all that draconian.

The Vanguard team says you can dampen the risk by using an adaptive withdrawal strategy for the first five years of retirement. Some years you get what you expect, other years a little less, but overall you can likely avoid outliving your wealth, increase your bequest levels by 20%, and withdraw as planned for the remaining 30 years.

Take the hypothetical person who retired in 1973. They withdrew 5% from their portfolio in the first year. A simple calculation determined the withdrawal for year two: The researchers multiplied the portfolio’s new value by 5% and compared that with the $25,000 withdrawn the first year. If the new figure were higher than the prior figure, then year two’s withdrawal could be increased up to 5% over the previous year. But if the new figure were lower, the year two withdrawal would also be lower, though not below a predetermined floor. In this case, the researchers used 2% as the maximum reduction in any given year. The idea was to repeat that every year for five years, then withdraw normally after that.

Even the seemingly small 2% reduction in withdrawal dollars, they found, had big consequences for the retirement portfolio. While the retiree still felt the impact in their planned bequests, they did not outlive their assets.

“This strategy eliminates the risk of portfolio depletion for all bear market retirees, even those who retired into the Great Depression and the tumultuous late 1960s and 1970s,” the Vanguard researchers wrote. “These periods represented the greatest risks in our almost-century’s-worth of data. For both groups [bear market and bull market retirees], overall retirement income remained largely at the same level.”

For clients who don’t like the idea of variable income, the Vanguard team released its second report in April of this year, called “What Can New Retirees Withdraw From A Portfolio? A Scenario Analysis.” (This time Khang and Clarke were joined by David Pakula.) The team updated its economic assumptions with more current figures, such as higher inflation and moderate-to-low stock and bond returns for the next decade. The researchers determined that retirees leaving work in 2022 could take fixed withdrawal amounts expressed as a percentage of the initial portfolio balance and avoid depletion in 85% of their simulations over 30 years. The percentage ranged from 2.8% on the downside to 3.3% on the upside.

“Compared with the 4% rule, these estimates are low, but hardly catastrophic,” the researchers wrote in the 2022 study. “Even if the prospective return environment mirrors the worst regime in the past 60 years, analysis suggests that retirees can count on a 2.8% withdrawal rate. And for investors approaching retirement now, that rate would be applied to portfolio values that have benefited from strong stock and bond returns over the past few decades.”

That point was seconded by Alicia Munnell, director of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College, when she assessed the immediate future for retirees.

“It’s never fun to enter a retirement in a down market, but we have to put it in perspective. There were soaring gains in 2020 and 2021,” she says. “Now, once you’ve got those gains they feel like they’re yours and when the market goes down it feels unfair. The challenge is that you want to use your assets to support yourself so you can put off claiming Social Security as long as possible, because that is the most valuable source of income for a lot of people.”

For new retirees who have to take Social Security now, there’s still an upside in that next year’s cost of living increase should be 8.5% and the Medicare Part B premium shouldn’t go up at all.

“When things are uncertain, if you have an option and don’t hate your job, I would try to keep working at least until there’s more certainty,” Munnell advises. Or at the very least new retirees should use their cash first to keep their equities in place. “Try not to have to realize your losses.”