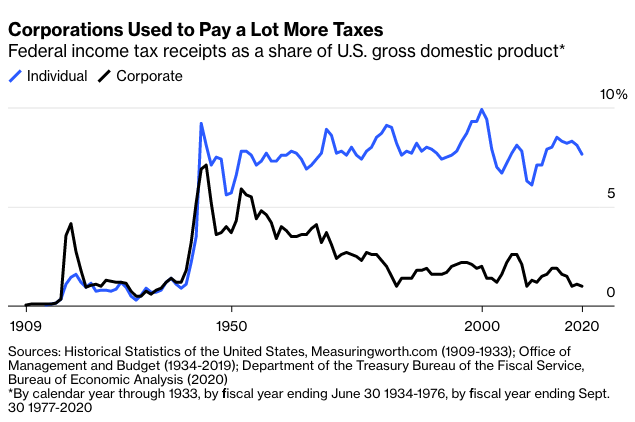

There are few policy discussions that can’t be improved with a chart that goes back more than century. So as the corporate income tax emerges as a leading focus of President Joe Biden’s plans to raise money for infrastructure and other priorities, here’s a look a how much money the tax and its precursor, the corporation excise tax, have brought in since 1909 — with individual income tax revenue alongside for comparison.

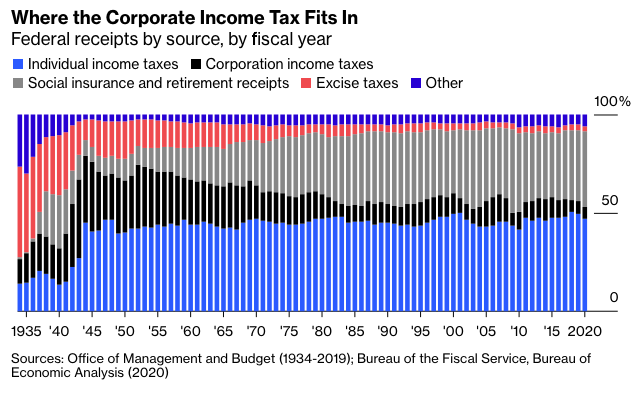

The corporate tax predated the individual income tax by four years, and during World War I it raised far more money. In the 1920s and 1930s the two brought in similar shares of federal revenue, although in those days excise taxes on alcohol, tobacco and other products sometimes brought in even more. Nowadays the corporate income tax comes in a distant third among the federal government’s revenue sources, far behind not only income taxes but social insurance taxes (Social Security and Medicare) at 6.2% of federal receipts in the fiscal year that ended in September.

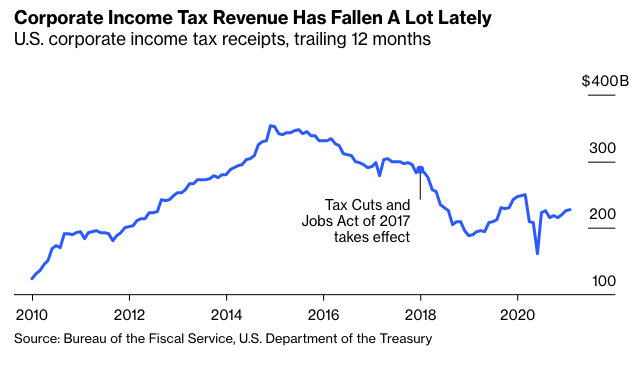

What happened to the corporate income tax? Well, one thing is that the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 passed by the then-Republican-controlled House and Senate and signed into law by then-President Donald Trump slashed the top rate for corporations from 35% to 21%. The resulting dip in revenue is quite apparent in monthly tax data.

Also apparent, though, is the decline during the three years before the tax cut. That can be chalked up in large part to the business-focused “mini-recession” of 2015-2016 — corporate income tax receipts tend to be extremely cyclical — but there was also a wave of “inversions” in which U.S. corporations merged with foreign companies and shifted their headquarters overseas to avoid U.S. taxes. And as is apparent from the top two charts, declines in corporate tax revenue aren’t exactly a new thing.

To restate: It’s important not to understate the impact of Trump’s tax cut, as corporate income tax receipts fell by $91.9 billion, or 68%, in the year it took effect despite an acceleration in economic growth that year. The Joint Committee on Taxation’s final assessment before Congress approved the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act pegged the corporate rate cut as the bill’s single biggest revenue loser — at an estimated $1.35 trillion over 10 years — and subsequent evidence seems to indicate that it is reducing tax receipts by even more than expected. Yet it’s also important to acknowledge a context in which corporate income taxes had long ago ceased to be a major pillar of U.S. government finances.

Which bring us back to that question of what happened to the corporate income tax. The main answer seems to be that, through a mix of action and inaction, U.S. policy makers opted to stop taxing businesses so much.

In the 1950s, big U.S.-based corporations were so dominant globally and so closely identified with their home country that some executives seem to have perceived their high tax burden as something of a patriotic duty. When a senator asked General Motors Co. President Charlie Wilson during his confirmation hearing to become Secretary of Defense in 1953 if his stock ownership in and loyalty to GM might result in conflicts of interest at the Pentagon, Wilson famously replied:

I cannot conceive of one because for years I thought what was good for our country was good for General Motors, and vice versa. The difference did not exist. Our company is too big. It goes with the welfare of the country. Our contribution to the Nation is quite considerable.

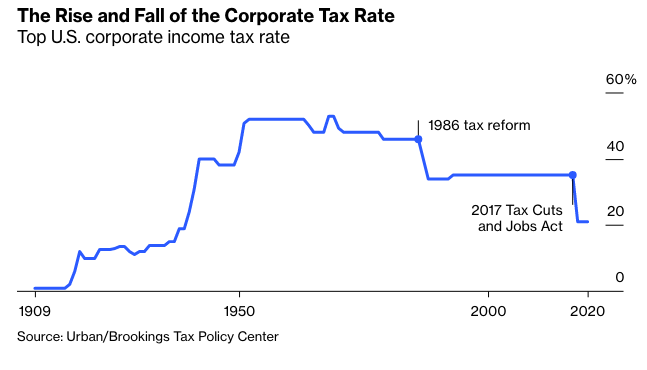

In subsequent decades, GM and other big companies were battered by foreign competition at home while in some cases drawing higher profits from operations overseas. Patriotism fell out of favor as a justification for corporate decisions, differences in corporate tax rates between countries began to matter more and economic theories that emphasized the costs of taxing investment and production were ascendant. Congress began to lower the corporate tax rate, at first gingerly in the 1960s and 1970s and then with a big drop in the 1986 tax reform law (which was accompanied by a fair amount of loophole-closing).

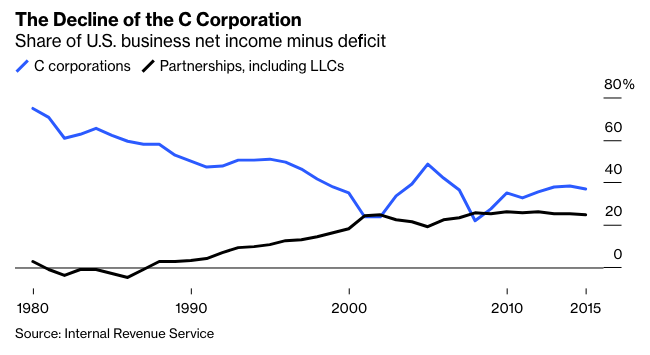

More quietly, policy makers began making it easier and easier to build and maintain a large business in a form other than the traditional corporation, aka the “C corporation.” Two early alternatives were the S corporation and real estate investment trust, created by Congress in 1958 and 1960 respectively. But the most important has been the partnership, especially in the limited partnership and limited liability company forms that state legislatures and the Internal Revenue Service have given more leeway over time to operate as big businesses. Full disclosure: this column is published by one of those big businesses, Bloomberg LP. The LP stands for limited partnership.

An advantage of these structures is that they don’t pay tax at the entity level. Income simply passes through tax-free to the owners, who then pay personal income tax on it. A disadvantage is that these earnings can’t be retained at the entity level as with a C corporation, where the owners are only taxed when they receive dividends or sell shares for capital gains. Some of the decline in corporate tax revenue thus reflects a simple shifting of business tax revenue into the individual income tax category. But since pass-through entities and their owners on the whole pay taxes at lower combined rates than corporations and their owners, there has been real revenue loss too.

Those losses have been exacerbated by the fact that fewer and fewer of the owners of America’s corporations are fully liable for income taxes on the dividends and capital gains they receive. According to a recent accounting by Steve Rosenthal and Theo Burke of the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center, about 40% of the shares of U.S. corporations are now in the hands of foreign owners who pay U.S. tax on dividends but not capital gains and 30% are in tax-deferred accounts such as pension funds and 401(k)s, with another 5% belonging to nonprofits that pay no income tax at all. In 1965 close to 80% of U.S. corporate shares were owned in fully taxable accounts, now only 24% are. A long-standing argument against the corporate income tax is that it amounts to double taxation, as income is taxed first at the corporate level and then again as dividends and capital gains. But now that most corporate shareholders aren’t fully taxable, that doesn’t really compute.

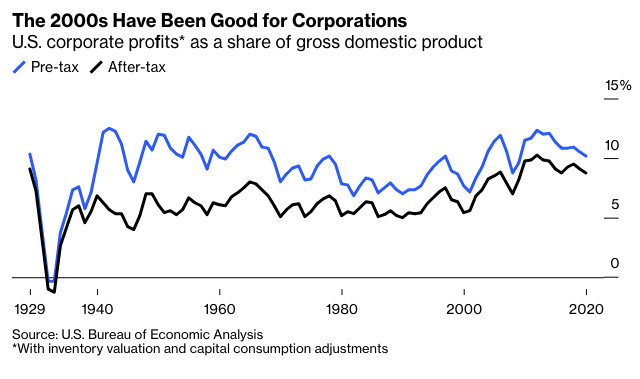

This shift away from taxable shareholders does at least seem to have mostly played out, with their share of U.S. corporate ownership about the same in 2019 as in 2008. Corporations’ share of business net income also seems to have stopped falling around 2000. Over the past two decades, in fact, U.S. corporate profits have boomed, with pre-tax profits returning to levels (expressed as a share of gross domestic product) last seen in the corporate glory days of the 1950s and 1960s, and profits after federal and state corporate income taxes the highest on record.

These high profits are evidence in part of the rise of the new natural monopolies of the tech and internet era, companies such as Microsoft Corp., Apple Inc., Amazon.com Inc., Alphabet Inc. and Facebook Inc., the five of which together account for around 10% of total U.S. corporate profits. These companies earn a lot of that income overseas, and the intellectual-property-dominated nature of their businesses has enabled them to shelter much of it in a sort of stateless, taxless corporate utopia, with taxes due only when the money is repatriated to the home country.

A new intellectual argument for low corporate taxes also gained strength. When a corporation pays taxes, the cost eventually has to fall on somebody — as Mitt Romney once said, “corporations are people, my friend.” It was long assumed that shareholders bore most of this cost, but in recent decades some economists have concluded that in a world with lots of capital mobility, corporate taxes can actually hit workers hardest, because unlike investors and their money they can’t easily move from country to country to avoid taxation. Raising corporate taxes is thus tantamount to cutting wages, my fellow Bloomberg Opinion columnist Michael R. Strain argued just last week.

Then again, Strain went on to cite estimates from the Tax Policy Center and Congressional Budget Office that workers bear 20% to 25% of the corporate tax burden, meaning that shareholders, customers and others still get stuck with most of the bill. The knowledge that workers probably bear some of the burden of corporate taxes is a useful corrective to popular notions of who pays them, but it doesn’t tell us exactly how high corporate taxes should be.

The general trend has definitely been downward, with the average statutory corporate income tax rate in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, the club of affluent democracies, declining from 32.3% in 2000 to 23.7% now. Here in the U.S., in part because reducing corporate taxes seldom gets more than single-digit support in public opinion polls, the top rate had remained stuck at 35% since 1993. But by early in the last decade there was bipartisan agreement that it should be reduced in conjunction with reforms to make income-sheltering harder. President Barack Obama wanted to cut the top rate to 28%. House Speaker Paul Ryan and the Business Roundtable wanted to cut it to 25%.

Then Trump ran for president in 2016 promising a 15% rate, and won. This pushed Ryan and other Congressional leaders to aim lower than they had previously been planning when they started writing the 2017 tax bill, with the first draft of the legislation proposing a 20% top rate and lawmakers eventually bumping that to 21% to cut the estimated costs slightly. At a 28% or even 25% rate the law’s corporate provisions might legitimately have been considered “tax reform,” given that the changes other than the rate cut raised taxes by an estimated $700 billion over 10 years. At 21% it was mainly a tax cut. It was also inexplicably accompanied by a tax cut for many pass-through businesses that left the domestic tax disadvantage for corporations largely in place.

Supporters of the legislation point to the subsequent dearth of corporate inversions and increase in repatriations of foreign earnings as evidence of its success. But they have come at a big cost, revenue-wise. At just 1% of gross domestic product in the 2018 and 2020 fiscal years (it went up to 1.1% in 2019), U.S. corporate income tax revenue has since 1921 only been lower for a few years during the Great Depression. It’s also fourth lowest among members of the OECD, ahead of the not-exactly-illustrious trio of Greece, Hungary and Latvia. It doesn’t seem hard to make the case that it ought to be a little higher.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He was the editorial director of Harvard Business Review and wrote for Time, Fortune and American Banker. He is the author of The Myth of the Rational Market.