Equities keep hitting record highs and volatility hovers near historic lows, all while geopolitical tensions abound. As a surreal bull market staggers onward, Bloomberg Markets asked around for reasons to worry.

Quant Quake 2.0

When you look back at the financial crisis, the quants stand out as the canary in the coal mine. Model-driven funds experienced massive losses in August 2007—a full year before the rest of the financial system came to its knees. The event, dubbed the Quant Quake, may have resulted from one large liquidation: Leveraged quant funds pursuing similar bets then unwound at an unprecedented clip. AQR Capital Management, a $208 billion quantitative money manager, was among them, and the experience left some lingering bruises—and worries about the future.

To AQR’s founder, Clifford Asness, Quant Quake 2.0 is inevitable. Quant strategies are popular, and popularity is what makes a coordinated action, whether it’s a run on the bank or a crash, possible.

“In the early ’90s, when I first started doing these strategies, they were relatively unknown. There was a low chance of a significant amount of dollars fleeing at once,” he says. “What we don’t have now is a monopoly that protects you from common actions.”

Asness is far from a neutral observer. Investors in quant land have been particularly keen on the strategy behind AQR’s success that he pioneered: factor investing, which groups stocks based on market-beating characteristics such as volatility or value. That success, he concedes, heightens the likelihood of a historically large crash, an “event with a big left tail.” But that isn’t enough to deter Asness from factor investing.

“We have a whole body of literature by smart people confirming what we think, another 25-or-so years of out-of-sample evidence that our strategies work and, despite all of this, reasonable pricing of these strategies,” he says.

The financial system also looks healthier than it was during the Quant Quake: less leverage, reasonable valuations, more conservative implementations. According to Asness, future crashes will be short-lived, a survivable “fact of life going forward and a consequence of being in good, well-tested strategies that other people know about.”

Even so, there’s one scenario that concerns him, because of the ubiquitous media spotlight on the markets: a vicious feedback loop of selling fueled by negative coverage. “Crashes have a little bit of psychological magic to them. August of ’07 went by relatively unnoticed. I don’t think that will be the case this time,” Asness says. “In this case, the revolution will be televised. What kind of feedback loop that creates is a wild card I worry about.”

Still, like most investors humbled by their experiences in 2007, the legendary quant isn’t ruling out any possibility for when Quant Quake 2.0 rolls around. “I expect an event to be not as bad. Or maybe as bad because we missed something. We’re honest nihilists about it,” he says. “With all that said, we’re still guessing. These are wild events.” — Dani Burger

The Wild Card

Bill McNabb took over Vanguard Group Inc. just as the financial crisis hit. He’s since helped the buy-side behemoth add more than $3 trillion to its assets under management. As he prepares to leave the post of chief executive officer at the end of 2017, he says his biggest worry isn’t a big correction so much as “some sort of cyber event.”

“Cyber is just morphing constantly and is probably the No. 1 risk that the whole system faces—not just financials, not just investment firms, not just financial services more broadly, but the entire corporate infrastructure,” he says.

Of course, you need only look at Sony, Anthem, or Equifax to get a sense of the scenarios that worry the McNabbs of the world. And defending against a WannaCry-like ransomware scenario doesn’t come cheap. “Our budget [for cybersecurity] has been multiplied by 10 times over the last seven or eight years,” McNabb says from his office in Malvern, Pa. “I don’t see any end to that. In one sense that’s a shame, but there are a lot of bad actors, so you’ve got to be willing to do it.”

While cyber requires constant vigilance, McNabb’s a little more passive—ahem—about the markets. “Valuations are starting to get pretty rich,” he says. “You certainly worry about a flash point. A 10 to 15 percent move in equities would not be unprecedented in history from these kind of valuations. And whether that happens in 6 months, in 12 months, or in 18 months … sooner or later it’s going to happen. To deny that and think some policymakers can navigate things so that we never have another correction again, that won’t happen. The markets need to cleanse.”

How do you say “Que será, será” in Pennsylvania Dutch? — Rachel Evans

China, China, China

Kyle Bass, the founder and chief investment officer of Hayman Capital Management LP, earned his reputation as a Cassandra when his misgivings about subprime mortgages, which he shorted, proved correct. He’s had his eyes on China for the past few years. Now he has a new noneconomic catalyst that could finally put a ball in motion: President Trump. “The politics are likely to accelerate the economics,” he says.

Bass says China, the world’s second-largest economy, is overstating the health of its banking system, and doing so for political reasons. “You can’t grow your banking system 1,000 percent a decade and only grow your GDP 500 percent and not have a loss cycle,” he says. “When you’re moving from an export-led economy to an internal consumption-based economy, you have to remember that all the loans in your banking system were lent to your old economy and are going to have to be restructured.” About 20 percent of China’s banking system is nonperforming, he estimates—a far cry from the official low-single-digit number.

Bass isn’t the only China bear, of course. Zhu Ning, deputy director of the National Institute of Financial Research at Tsinghua University in Beijing, raises similar themes in his 2016 book, China’s Guaranteed Bubble: How Implicit Government Support Has Propelled China’s Economy While Creating Systemic Risk. The huge amount of debt burdening the Chinese financial system, coupled with an overheated property market, poses broad risks to an economy that the rest of the world looks to for growth, he says. And any popping of asset prices could drag China into the kind of lost decade that Japan experienced in the 1990s, when debt-fueled growth and a red-hot property market screeched to a halt, Zhu says. “The government should allow zombie companies to default or go bankrupt,” he says. “It’s surprising to see the number of bankruptcies in China is even lower than that in Netherlands or Belgium.”

China’s hope, according to Bass, is that the country’s nominal gross domestic product will grow fast enough to rescue the economy from its massive banking problem. “And what I’m saying is that’s not going to happen,” he says. “If you’re going to use your FX reserve pile to maintain stability in your currency, and if you’re going to continue to lie about where you are from an economic and asset perspective in your banking system, then sooner or later economic gravity is going to take over.”

While Bass has been betting against China for years, he says the addition of Trump is an especially big X-factor, given the potential for his imposing sanctions on entities doing business with North Korea in an effort to “change the subject” from his domestic drama. That prospect would damage global trade—hurting the Chinese economy—inflicting “pain on their banking system a little bit sooner than it otherwise would have experienced.” And should the relationship between the U.S. and its biggest trade partner worsen, the knock-on effects for countries such as North Korea, Russia, and Taiwan could become catastrophic. “So financially speaking, it may be not as bad as 2008,” he says, “but kinetically speaking, it may be worse.” —Katia Porzecanski and Judy Chen

Watching the Clock

If you broke every hour of the trading day into quarters, none is quite as important—or as vulnerable—as the final 15 minutes. The period just before the U.S. stock market shuts at 4 p.m., when official end-of-day prices are set, is an Achilles’ heel in the otherwise fairly muscular $29 trillion market.

An entire exchange can go dark during normal trading hours without more than a hiccup for the rest of the market, because stocks can trade on any one of 12 official public venues. But at the end of the day, stocks return to their home-listing exchanges, where closing auctions determine final prices that affect millions of trading portfolios and retirement accounts. If a listing exchange fails during that auction—whether by internal error or an outside cyberattack—the backup system gets slippery.

There’s an official Plan B in the event this ever happens. It calls for two of the New York Stock Exchange’s sister venues to back each other up, with Nasdaq in reserve as an additional fail-safe. Likewise, if Nasdaq goes dark, the NYSE would step in as a reinforcement. (The exchanges organize periodic tests of the arrangement.)

But that plan hasn’t been put to the test in a period of extreme market stress, which means unanswered questions remain. Just one example: The NYSE has a group of human floor traders who play a role in the market close, but that system doesn’t exist on the all-electronic NYSE Arca or Nasdaq. (Representatives from the NYSE and Nasdaq declined to comment.)

A mishap in setting final stock prices could spin out to other types of securities, including options and over-the-counter derivatives, says Joanna Fields, principal founder and CEO of consulting firm Aplomb Strategies Inc. “There’s a ripple effect that could happen,” she says.

A couple of recent wobbles have snapped this vulnerability into focus. An almost three-and-a-half-hour outage at the NYSE in 2015—now the subject of regulatory scrutiny—left traders fretting over what would happen if the problem stretched through the close. The NYSE got its exchange running by 3:10 p.m. that day, escaping catastrophe. But this year another error snarled trading on NYSE Arca, the largest exchange-traded-funds-listing venue, derailing closing auctions for some products.

The playbook for handling problems around the close hasn’t been tested enough to be bulletproof, according to Bryan Harkins, head of U.S. markets and global FX at Cboe Global Markets Inc. “We’re certainly not there yet as an industry,” he says. — Annie Massa

The Index Trap

Diversification isn’t always the safety net it appears to be. So says Jared Dillian, who ran the exchange-traded-funds desk at Lehman Brothers in 2008 and is now editor of the market newsletter the Daily Dirtnap, an investment strategist at Maudlin Economics LLC, and a Bloomberg View contributor. “Retail investors who are buying ETFs or indexed funds are being sold on the idea that they’re diversified,” he says. “So if you buy an S&P 500-indexed fund, it’s like ‘Oh, I own 500 stocks—I’m diversified.’ ”

What most retail investors don’t realize, he says, is that the trade is very crowded—like 20 million-other-people crowded. According to Dillian, you need only look back to when commodity indexing became popular a decade ago for a sense of how things could go wrong. “When money goes indiscriminately into an asset class, valuations don’t make sense anymore,” he says. “What happened in the commodity markets is those flows reversed, and that entire trade unwound—and it unwound very quickly.”

Crowded indexes don’t bring about a financial crisis, of course. You have to differentiate between what happens in the stock market and what happens in the economy, Dillian observes. And he says he’s not a “doomsday” guy; he’s just trying to point out that a selloff is a possibility—and that it could be 1, 5, or even 10 years away. “You could have a scenario where this trade unwinds, the stock market is down 30 percent, and we’re still not in a recession—that’s possible,” he says. “I would hesitate to call it a financial crisis, but I would call it an unwind, and if it unwinds, it has the potential to be on the scale of some of the big market crashes.” —R.E.

Bubblicious Bitcoin

The debate on whether bitcoin is a bubble about to burst or a great investment continues to divide the financial world. Billionaire bull Mike Novogratz has said he plans to “make a whole lot of money” on the boom; JPMorgan Chase & Co. chief naysayer Jamie Dimon called people who buy bitcoin “stupid.” Regardless of where you stand, the impact of a potential crash may be rather limited considering the relatively niche appeal of cryptocurrencies—although that may be about to change.

The entire cryptomarket is relatively small: $200 billion. Yet that’s already 10 times bigger than it was at the start of 2017. And the potential approval of bitcoin futures and ETFs means digital assets could soon start seeping into the mainstream. Themis Trading LLC partner and co-head of equity trading Joseph Saluzzi says cryptocurrency derivatives, including options and ETFs, are risky because they legitimize assets with prices derived from unregulated exchanges subject to manipulation and fraud. According to Saluzzi, this frontier could start to look like the collateralized debt obligations that contributed to the 2008 financial crisis. “Cryptos will be given a wrapper that makes them sound and look good,” he says—then they could seep into portfolios everywhere.

Cryptocurrency risk could also spread into the broader economy if crypto-backed loans gain steam. Although the idea is still in its infancy, there already are startups offering dollar loans against digital assets such as bitcoin, which they hold as collateral. If the digital asset crashes, so will borrowers’ ability to pay back the loans. — Camila Russo

Recessions Are Inevitable

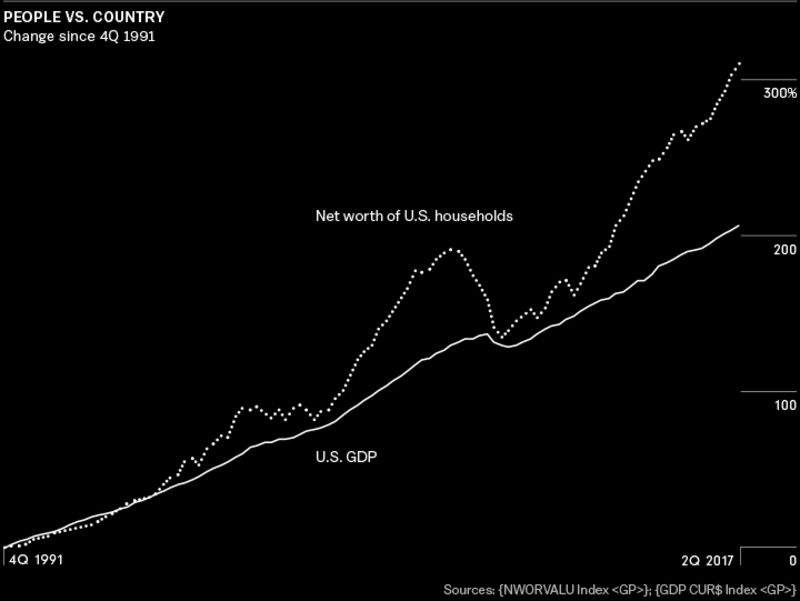

One of Tad Rivelle’s favorite charts shows the widening gap between the value of U.S. household assets and GDP growth—a sign the economy is heading for a fall. Prices for stocks, bonds, homes, and even art that make up total household net worth have outrun U.S. GDP growth for years. This is an unsustainable deviation, according to Rivelle, CIO at TCW Group Inc., which oversees about $200 billion.

The gulf is wider than before the bubbles that preceded two other notable recessions: the dot-com crash of 2001 and the housing crash of 2008. “Financial instability tends to follow periods when asset growth has been disproportionate to underlying measures of income,” Rivelle says. “People usually say a recession happens because consumers stopped spending. What really happens is the economy becomes malformed.”

Recessions are an economic “feature, not a bug,” according to Rivelle, who co-manages the $80.4 billion Metropolitan West Total Return Bond Fund. They also offer opportunities for the well-prepared. The MetWest fund’s best year was 2009, when it returned 17.3 percent as the U.S. economy hit bottom and low-cost assets abounded. “Our best times historically were when there’s blood in the water,” says Rivelle’s co-manager, Stephen Kane.

Adverse events can occur months or years before a financial cataclysm, according to Kane and Rivelle. Ameriquest Mortgage Co., one of the largest U.S. subprime lenders, announced plans to close all its branches in May 2006, more than two years before Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy and the global financial crisis ensued. “The catalysts are invisible until they’re visible,” Kane says.

What’s most troubling for markets now, the two say, is that low and negative interest rate policies drove up prices and forced investors to accept more risk in their hunt for yield. “When the Europeans and the Japanese went to negative rates, you sort of knew that the central banks were jumping the shark,” Rivelle says.

Historically, recessions begin when central banks overshoot their rate hikes, tightening credit to take the steam out of growth. The Federal Reserve started hiking rates in 2015. The European Central Bank has signaled plans to dial down its accommodation programs. For investors, that means it’s time to worry about the return of—not just the return on—your money, according to Kane and Rivelle.

In other words, they say, you might want to consider an insurance policy. Harvest some profits from stock gains, shift fixed-income holdings away from high-yield and emerging-market debt, and add ballast to portfolios with higher-quality bonds—even if a downturn remains years off.

“I’m highly confident my house won’t burn down in the next year, but I still have insurance on it,” Rivelle says. “The challenge,” Kane adds, “is to not pay too much for insurance.” — John Gittelsohn

A Collapse of Confidence

The European chairman of Houlihan Lokey Inc., David Preiser, is an alchemist of sorts. He picks up pieces of broken companies and makes something out of them. And what he sees as he focuses on the future isn’t pretty.

“Until 2008, people thought debt problems were confined to specific sectors,” Preiser says. “But when the bubble burst, trouble popped up in unexpected areas.” People assumed certain sectors were very liquid, he recalls, only to learn that being unable to sell in an illiquid sector could also bring down prices in more liquid ones. In other words, markets were more correlated during a crisis than previously thought. “Financial complexity brings prosperity but also increased fragility,” he says.

Similarly, the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers brought back the issue of counterparty risk—something people had almost forgotten. “Since then, it’s been a long and slow recovery,” Preiser says. “But the underlying problem remains: The entire edifice is built on confidence, and that can evaporate pretty quickly. The next global crisis will stem from failure of confidence somewhere.”

Preiser thinks the European Union and the euro zone will be among the likely triggers. While the EU has weathered a number of crises and even stared into the Greek abyss more than once, something changed on June 23, 2016, when the U.K. voted to go its own way. “For a long time, Europeans blinked and stuck together,” he says. “But with the Brexit vote, one of the main tenets has been undermined.”

Elections and public opinion on the Continent seem to indicate otherwise, Preiser acknowledges. His point is that when the euro zone’s next crisis happens, there will be less confidence that the group will stick together. “So far, European countries have chosen to stay in,” he says. “But in the long term, the EU is not stable as constructed; the essence of the problem is that you have a monetary union without fiscal union. If confidence is shaken in the European structure, markets will sell off, big time.” — Luca Casiraghi

Keeping the Lid on Japan

Fiscal weakening, as ever, poses risks, says Ryutaro Kono, chief Japan economist at BNP Paribas. If no decisive action is taken to fix the nation's fiscal woes, he says, the yen could weaken to well beyond 150 per dollar—compared with around 111 now—and inflation could accelerate to 4 to 5 percent or even higher, from the current 0.7 percent.

The good news is that the inflation spiral might not take off until around 2025. The period around that year is key, Kono says, because by then baby boomers will be 75 or older, with medical and nursing costs rising sharply. “Even if by a stroke of good luck we’re able to make it through 2025,” he says, “by the time baby-boomers turn 85 in 2035, nursing costs will surge.”

Japan already has the heaviest debt load among industrialized countries, equivalent to about 240 percent of gross domestic product, according to International Monetary Fund estimates. One possible further trigger of yen weakness would be credit-rating downgrades of Japanese banks and of the government itself. Kono says that would make it difficult for lenders to borrow foreign currencies and force them “to sell yen to buy dollars, just as they did during the 1998 financial crisis” in Japan.

“The biggest problem is that as a result of monetary policy that keeps interest rates excessively low, fiscal discipline is weakening, and that may be promoting fiscal expansion,” Kono says. Should the government not act until after inflation has already accelerated to 4 to 5 percent and the yen is far weaker than 150 per dollar, it may have to raise the sales tax to as high as 25 percent. As it is, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has delayed lifting the consumption tax to 10 percent from 8 percent.

A crisis in Japan could send ripples through the global economy. The global market, for example, might begin to demand higher interest rates to compensate for holding bonds of other countries that are also saddled with an aging population and large public debt. —Takashi Nakamichi

The Oil Trigger

“Don’t dismiss oil just because it smells like yesterday’s trade,” says Sir Michael Hintze. The British-Australian head of CQS U.K. LLP, the hedge fund he founded at the turn of the century now worth $14 billion, warns the one thing that could upend the status quo assumptions about global growth is a redux of cratering crude.

“Such an event has the potential to spark a wider contagion,” he says. Hintze points to $35-a-barrel oil as that trigger point. That price may not feel imminent—and he emphasizes that he doesn’t see this scenario panning out anytime soon because of the recent developments in the Middle East—but that doesn’t make it improbable. The 64-year-old Hintze, a staple of the conference circuit and a member of the Vatican Bank board, says investors will have hell to pay if they turn a blind eye to what another spell of oil below $30 can wreak on the global financial system.

Worse still is the risk that price level proves sticky, which could happen if suppliers such as Saudi Arabia and Russia keep pumping oil to fuel their fiscal compulsions. Such a scenario would hamper U.S. energy producers with low credit ratings and impair their ability to come good on their dues. And with credit investors heavily exposed to those companies, the resulting impulse to sell and then rush to contain losses could spread to other parts of the financial system. Add to that the number of ETFs that have become prominent credit investors, Hintze says, and you have a stress point to be wary of. — Sridhar Natarajan

All These Eggs Are in One Basket

A somewhat obscure corner of the U.S. financial markets, one buried deep within the plumbing of the debt markets, is about to become the only corner of its kind.

Come mid-2018, just one entity—the Bank of New York Mellon Corp.—will be responsible for ensuring that almost $2 trillion of securities financed by so-called repurchase agreements are cleared and settled each and every day. JPMorgan Chase, its lone longtime rival, has elected to exit the business, in part because regulators pushing for banks to boost capital and cut leverage made the dealings costly and onerous. So while Bank of New York already was the dominant of the two—accounting most recently for 80 percent of market share—there’s no Plan B anymore.

Even as Bank of New York has plowed billions into improving and upgrading its technology and systems, some investors worry that any sustained outage could cripple the country’s debt markets. Not only do repos support liquidity in the $14.3 trillion Treasury market, but the financing they provide also helps grease the wheels of trading in assets as varied as stocks, corporate bonds, and currencies.

“A single point of failure in the U.S. government-collateralized repo market, which is huge and is essentially the liquidity engine for the country, is a little bit unnerving just in itself,” says Adam Dean, managing director at Square 1 Asset Management Inc. “It’s not an ideal situation.” — Liz Capo McCormick

The Fire Next Time

You ain’t seen nothing yet, says Deepak Gulati. The CEO and CIO of Argentiere Capital AG sees the next crisis having a broader impact than the last. “Risk premia are at the lowest ever, and in some cases you are now being paid to take insurance on risk,” says Gulati, who oversees about $1.2 billion. “Premia cannot drop much further.” Simultaneously, he adds, risk-reward from owning volatility is higher in many investment classes than even in 2007.

Volatility in equity markets is mispriced, Gulati says. A shock could cause something to falter and volatility to rise quickly. What’s more, the market has zero protection to the downside, he says, because everybody is looking for yield. As a result, any adverse effects will be amplified.

While the last crisis “was all about greed, the next crisis will be about need,” he says. “Back then we had about 15 investment banks trying to generate profit. Now it’s thousands of market participants hunting for yield. And that’s because we’ve pushed Grandma into toxic investments. When those leveraged trades unwind, and they will end eventually, investors will get hurt.” —L.C.

Even Optimists Get Pessimistic

Before he says anything else, Dan Fuss wants to make one thing clear: He’s an optimist. Still, there’s one thing the veteran investor with 59 years of experience in the market has noticed lately that gives him pause. It’s about how the U.S. is changing the way it wants to relate to foreign counterparts. He’s starting to sense a growing tentativeness among clients in Asia, in particular. “They’re wondering what’s happening, just like many of us are,” says Fuss, who helps oversee $261.3 billion in assets as vice chairman of Boston-based Loomis, Sayles & Co. “They’re starting to make some decisions that normally would have been investing in U.S. assets and they’re not—they’re investing elsewhere.”

It reminds Fuss of 1973-74, the worst period for markets he’s encountered in stocks or bonds. In February 1973, following the Watergate break-in the year before, the U.S. House of Representatives appointed a select committee to investigate President Richard Nixon for “high crimes and misdemeanors.” By the time Nixon resigned in August 1974, U.S. stocks had fallen 25 percent in just over two years. “Distrust in the political process was very, very severe,” Fuss says. “Discussing this with many of our folks these days, they don’t quite understand that: How can that lead to a bear market? But I know what it felt like at the time. It was awful. Will this be that? I certainly don’t think so, but as it was happening, I didn’t think it was going to be that bad.” Overall, Fuss, like others, has been surprised at how stable markets have been recently.

While it’s difficult to prepare for geopolitical disruptions, one thing Fuss is trying to figure out is the best investment strategy at a time when rates are finally rising from artificial lows. For its part, Loomis Sayles has cut the maturity of its funds. For example, the firm has reduced the maturity of its bond fund by half, to 6.5 years; duration is now even shorter than that, at 3.2 years.

The $13.3 billion Loomis Sayles Bond Fund boosted its buying reserves to more than 20 percent of total assets, up from less than 2 percent two years ago. The idea, Fuss says, is to buy any decent credit or sector on the cheap once it ends up taking a hit.

As for the next crisis, he’s candid in admitting that he’s never seen one coming. So his warning: Don’t believe anyone who says they have. — Nabila Ahmed

This article was provided by Bloomberg News.