The kids who are the biggest drain on their parents’ finances are those who never learn to truly fly on their own. That’s true for a number of our clients as well as people around the country.

Life takes many unexpected turns and we face financial calamities we can’t control. But the good news is that the financial discipline of clients’ children is something over which the parents have a great deal of control. But they need to seize it.

It’s easiest to start when kids are young, making sure they know that they are expected to grow up and become self-sufficient.

What if, however, clients are already nearing retirement age or have stopped working? The chance to give a child a sense of financial independence has likely already passed.

When we see families lose money for those reasons, the conversations are difficult. Typically, one or both of the parents will tell me, “It’s so much harder for our children these days. Look how expensive homes are now. Look how expensive cars are. How can little Johnny (now age 35), afford these things without our help?” If they aren’t there to help their kids, they believe, then the kids won’t be able to have the kind of life they’ve had. And, of course, they love their children and want them to be happy.

It can be difficult for all of us to let our older kids, even those who have already started college or work, make decisions without our input. I have been there myself. My daughter, Lisa, quit her job and bought a one-way ticket to Southeast Asia. She said, “I am burned out from work and need a break, so I’m going to go to Thailand.” I didn’t try to persuade her to stay here or to get another job. I didn’t do anything but wish her safe travels and ask her what she was doing for Christmas.

When I tell this story, some people are appalled that I would let my daughter, who was 25 at the time, go to Thailand by herself. But she was an adult (if young) and she could make her own choices. Sure, I sometimes worried about her and felt a bit anxious when I didn’t hear from her for a few weeks.

But this was her adventure, not mine, and it ended up being a great experience for her. She traveled the country, enjoyed learning about a culture very different from the one she’d grown up in, met many wonderful people who were on similar adventures, and really learned to rely on her own resources. Eventually, she came back home, ready to get back to work. She is now settled in the Cayman Islands, teaching accounting and economics. It is a wonderful life she lives!

The best thing I could do for her was let her go and find her own way. She is smart and talented, and I knew she would figure it out. But I didn’t give her any money. Friends say, “How can she afford to do that?” I tell them, “That’s her issue. If she can’t afford it, she’ll come home and get another job.” But she did fine.

And that is my point when I share this story. My daughter did fine. And most kids will do fine without parents’ help, too.

Sometimes, parents are wedded to the idea that they are so important in their children’s lives that the kids can’t get along without them. They want to stay relevant. But there are better ways to be relevant in your children’s lives than to encourage them to depend on you.

Barbara Schelhorn, a colleague of mine here at Sullivan, Bruyette, Speros & Blayney, notes that when people have problems saying no to their adult children’s requests for money, it’s usually because the parents are people pleasers with a strong desire to make their children happy. “They want their children to love them and to view them as a good mother or a good father,” Barbara says. “Every parent wants that, of course, but when that desire is too strong, when the relationship is out of balance, there are going to be problems.”

At this point, there are two separate questions: (1) Does the money they are giving jeopardize their own financial health and future? (2) Does doling out cash really help their child? If a child has a health problem or a setback of some other kind, that’s one thing, but often the child’s dependence is based on a dynamic between the parent and child. If the amount of money they are gifting is small enough (or if they are wealthy enough) that it has no significant negative impact on their finances, then their continued support may be fine. But for many people, that will not be the case: The amounts are large and the impact is likely significant.

Even if clients are able to afford the cash, they still need to answer the second question: Are you really helping your child when you allow her to remain dependent?

Am I Jeopardizing My Own Future?

Entry into the adult world can be tough, and many parents try to soften the blow for their children. They don’t want to think of their kids sitting in a tiny apartment eating instant Ramen (even though that’s what they did), so they pony up until the kids can get on their feet. The problem comes when kids don’t pull things together quickly, or at all, or when parents’ contributions threaten to undermine their own financial security. Most couples nearing traditional retirement age need to continue to work, and they are having to work longer, only because they spend so much money trying to keep their children going.

More young adults are living with their parents than at any time since 1880. Among 18- to 34-year-olds, just over 32% are living with their parents.

It’s even more problematic when it’s older kids in their 40s, 50s or 60s who depend on their parents. In some instances, the children may simply not realize the toll they are taking on their parents’ finances. They figure their parents have enough money to go around, and never stop to consider that Mom and Dad may outlive the wealth. Parents who’ve always provided for their children may be unwilling or unable to say no.

When clients are making decisions about whether to come to their kids’ financial rescue, it’s helpful to think through all the outcomes of their decision, specifically the things that they don’t want to happen. For example, clients may never want to be dependent on their children or have the kids change their own plans so they can care for the parents later in life. Once they are clear about the worst-case scenarios they want to avoid, the clients can make sure they are heading toward an outcome that they do want. And if laying out large amounts of cash to help children reach their immediate goals will jeopardize their long-range plans, then clients may be undermining their offspring’s future happiness as well as their own.

No matter what our financial circumstances are, we all have to assess what we have and prioritize our goals. Start with the numbers: Tell clients to think through what they have and what they want, and build around that. Clients need to have an honest conversation with their financial advisor, who is experienced in projecting the costs of the things they want to do and can help them understand the trade-offs necessary to enforce their priorities.

Everybody should be evaluating the impact of their spending, no matter their income level or wealth. List all their priorities: “I want to remain financially independent.” “I want to take one nice vacation a year.” “I want to be able to help my child with her rent if she needs it.”

And if you can’t afford to do all the things you want, which ones are the most important? When it comes down to it, helping family tends to take priority over lots of other things. In most cases, parents and kids ultimately want the same things, and they just have to agree on how to get there.

One of my clients, “Ruth,” had been giving her daughter, “Heidi,” sums of money whenever Heidi expressed a need or a desire. Ruth was essentially handing a blank check over to her child with alarming regularity. But when I spoke to Heidi, with Ruth’s permission, of course, they were able to get on the same page.

I asked Heidi if she would like her mom to move in with her when Ruth had depleted her assets and was forced to sell her home. That put a new spin on the discussion. Heidi was truly unaware that her mom’s financial well-being was endangered by the money she was giving so freely. Since Ruth’s husband had passed away, her income was greatly reduced. She received only a fraction of the Social Security and pension income they’d been getting as a couple. Ruth would be fine—as long as she didn’t give all her assets away.

We all wanted the same thing: for Ruth to be happy and do well and not end up living with Heidi. We were able to agree on a small amount that Ruth could afford to give her daughter each year, given her financial picture, and that worked out very well.

Other scenarios haven’t ended as well, mainly because a child occasionally believes that his priorities are most important. If clients have a child who is adamant and the parent gives in, particularly if that parent is widowed and there is no other source of moral support when it comes to these tough decisions, then the parent may well choose to drain assets attempting to placate the child.

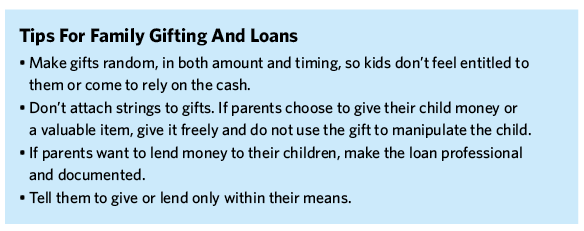

One strategy we have used for scenarios in which kids are coming and asking for money on an as-needed (or wanted) basis is creating trust accounts for the kids. The parents are then able to tell the children, “This is all you get. The trust will distribute a set amount each year, but you can’t come back and ask for more.” Sometimes the kid tries anyway, but our clients are able to say no and remind the children what was agreed upon.

We’ve also written loans from parents to children, formalizing the arrangement that way. A loan instrument in black and white, outlining the expectation of repayment, including invoices that are sent like bills, can be a powerful motivator preventing the child from asking irresponsibly for more money.

If the child should fail to repay, the loan is part of the estate, which can lessen tensions with other siblings. Trust me, the other kids in the family are generally not happy when one sibling is asking for and receiving large amounts of cash from Mom and Dad. A loan agreement can reduce the financial impact on the other children and take away some of the animosity that may result when parents gift a substantial amount of money to a child.

These approaches can provide structure and accountability, forestalling a slide down the slippery slope to a retirement account that has been hollowed out, perhaps unwittingly, by grown kids. Even if not all goes precisely according to plan, the structure creates a sense of deliberateness; it’s much easier to view and raise red flags if outflows are documented as loans or regulated by a trust or other agreement.