Traditional, non-guaranteed universal life insurance (often described in the insurance industry as “Current Assumption UL”) has been subjected to rather brutal criticism over the last few years, most recently in a September 2018 Wall Street Journal article that blamed the product for financial hardship being experienced late in life by many policy owners who purchased these policies back in the 1980s and 1990s.

But how much of this condemnation is truly warranted, and how much of it reflects a fundamental misunderstanding of how these products are designed to work when properly tended to?

What Is Current Assumption Universal Life?

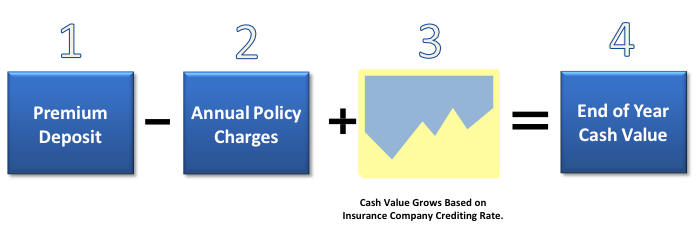

Current Assumption UL is a flexible premium permanent life insurance product that contains both an insurance component and an investment component. Like other permanent life insurance products: Premiums are deposited in the policy’s cash account, which is reduced by policy charges and increased by a crediting methodology set forth under the terms of the policy. What differentiates a Current Assumption UL policy from other types of non-guaranteed permanent life insurance is that the growth of the policy’s cash value is based on a flat crediting rate that is established by the insurance carrier and adjusted from time to time – rather than based on a flat dividend rate that is established by the insurance carrier and adjusted from time to time (a product referred to as “whole life”), based on the performance of an equity index that is collared by a cap and a floor (a product referred to as “indexed universal life”), or based on the actual investment returns of specific equity investments (a product referred to as “variable universal life”).

As illustrated above, projections of Current Assumption UL policy performance are based on the forecasting of two variables: (i) annual policy charges; and (ii) the insurance company’s crediting rate. While many life insurance policies provide that the insurance carrier may increase policy charges under specified circumstances (generally defined broadly by reference to the company’s expectations regarding future mortality, expense and persistency experience), this discretion is very rarely exercised and annual policy charges rarely deviate from schedule set forth at the time a policy issued (While there have been several instances in recent years where insurance carriers have increased policy charges in order to compensate for their own lower-than-expected investment returns, these increases have spawned a number of class action lawsuits that have largely been resolved or settled in favor of policyholders.). In contrast: The crediting rate, which is tied to the interest rate that the insurance carrier is able to earn on its portfolio of fixed income investments (i.e., bonds), changes regularly. As interest rates change (up or down), crediting rates on Current Assumption UL policies tend to follow suit. And for those whose Current Assumption UL policies have been dramatically underperforming, the primary source of the problem is that nobody has been monitoring the crediting rate changes and adjusting their annual premiums accordingly.

Understanding Policy Illustrations

When a Current Assumption UL policy is issued, an illustration is run to project how the policy will perform under the assumption that scheduled policy charges are not changed (a reasonable assumption, as noted above) and that the then current crediting rate remains constant (an unreasonable assumption, because crediting rates rarely do). It’s an imperfect system, but without the benefit of a crystal ball that can accurately predict future interest rate changes, it’s at least a good place to start (Policy illustrations also include an alternate set of “worst case” projections, but these are generally of no value because they’re based on the unreasonable assumption that (immediately after the policy is issued and continuing indefinitely thereafter) the crediting rate is reduced to the minimum rate allowed under the terms of the policy, and at the same time, policy charges are increased to the maximum level allowed under the terms of the policy. Given how infrequently policy charges are ever changed at all, it is understandable why few people take these worst-case scenarios seriously).

It’s also important to recognize that the amount that gets paid to the beneficiary at the death of the insured under most permanent life insurance products is a level death benefit that doesn’t vary based on the cash value of the policy. What that means is that as the policy builds cash value, the amount of pure life insurance protection that needs to be purchased to produce the policy’s death benefit gets smaller – reducing policy charges (which, after the first few years, are based largely on the difference between the policy’s death benefit and the policy’s cash value) and accelerating the buildup of policy cash value.

As a general rule, Current Assumption UL illustrations are intentionally designed to calculate the minimum annual premium necessary in order to keep the policy in force indefinitely (typically age 100, although policies are sometimes run to age 121), this approach to policy design is a big part of what differentiates Universal Life insurance from the primary alternative in the permanent life insurance arena: Whole Life. Whereas Whole Life policies operate somewhat like a “sinking fund,” with noticeably higher premiums that result in greater cash value but also reduce the policy’s economic yield, Universal Life policies are typically structured to be cost-efficient and maximize the rate of return that is ultimately realized on each dollar of premium. The theory behind minimally funding Current Assumption UL policies is that every additional dollar that doesn’t have to be used to pay premiums is a dollar (plus any future earnings on that dollar) that the insured’s heirs will receive in addition to the insurance policy’s death benefit. While this approach may seem risky given the uncertainty surrounding future crediting rate changes, it actually works quite well as long as policyholders and their insurance advisors actively monitor policy performance and adjust premium levels whenever there is a change in crediting rates.