Given the high-stakes nature of income planning, it's tragic that a significant segment of the financial advisor community embraces an income-generation methodology—the systematic withdrawal plan (SWP)—that is truly inappropriate for a large segment of clients. To be clear, I do not mean all clients. If your client is “overfunded,” a systematic withdrawal is perfectly appropriate. It is everyone else I’m referring to. Allow me to explain why continuing to embrace SWP works against the best financial interests of advisors.

For a long time, the deficiencies inherent in SWPs were camouflaged by an unprecedented, 14-year bull market that was engineered by never-before-seen levels of fiscal stimulus, combined with nearly $9 trillion in Federal Reserve money creation, combined with zero-percent interest rates. These measures inevitably propelled asset prices upward to heretofore unseen levels. It was, of course, unsustainable. Now, we find ourselves on the downside of those radical policies and the result is inflation, stock market losses, real estate losses, much higher interest rates, and extreme levels of economic uncertainty.

If all that is described above hadn't happened, we'd still have a massive problem in terms of inadequate retirement security. The reason starts with the common perspective among investment advisors that a market-based approach to income distribution planning is advisable enough to be their default option. American College Professor, and noted retirement researcher, Dr. Wade Pfau, determined in his work with RISA LLC that:

“…about 1/3 of the population is comfortable with the assumptions and preferences required to make ‘safe withdrawal rates’ work, but that leaves 2/3s of people looking for something else.”

The markets-centric worldview led to the development of AUM-based client segmentation. That construct works well for investors in the asset accumulation phase. However, AUM segmentation (“wealth segments”) is inadequate when investors transition to decumulation. Why? Traditional investor segmentation makes no room for the issues that matter most in retirement income planning, e.g., "flooring," risk-mitigation and longevity risk protection.

I developed Constrained Investor to be the practical, retirement income-focused replacement for AUM segmentation. It introduces three categories of investors who are nearing retirement or already retired. Any investor will fit into one of the three categories: underfunded investors, overfunded investors or constrained investors.

Constrained investor changes the calculus of income planning. It expands the scope of assessment of client needs by looking at the critical relationship between the retiree's investable assets, and the amount of their "must have" monthly income. It then furnishes a framework to determine which are constrained investors. Once a constrained investor is identified, the income planning methodology must be one that places the highest priority on risk mitigation.

Constrained investors have enough money to retire, but not enough to afford mistakes. Consequently, they have no margin for investment losses that occur due to emotionally driven decision-making. They simply lack the cash cushion to absorb the losses. Yet, they require long-term exposure to risk assets.

By incorporating safe monthly paychecks, and longevity protection through guaranteed lifetime income, the investor's behavior dynamics can change. Retirees gain the capacity to remain invested in risk assets through all market conditions. (IRONY: introducing an annuity is the investment advisor’s “best friend.” It facilitates the continuation of AUM. More on this below).

All constrained investors reach retirement with savings. That's good. However, the amount they've saved is not high in relation to the income they require to fund a minimally acceptable lifestyle (MAL). Therefore, the issue is less about the amount saved, and more about the relationship between that amount and the income that the retiree must have to fund his or hers’ MAL. MAL is defined as the amount of monthly income needed to cover all vital expenses, plus a minimum 30% buffer to support a modest amount of lifestyle expenses.

The top planning priority for advisors working with constrained investors is to mitigate risks that can reduce or even wipe out the client’s capacity to generate income from savings. Critical given today’s economy is the mitigation of timing risk. Ultimately, and even more financially significant, is the need to mitigate longevity risk.

Annuities are essential components in planning income for constrained investors. Some of you will find these words a turnoff due to longstanding prejudices against annuities. But it is easy to find annuities that have low fees, pay no commissions, and impose no surrender charges. Ongoing reluctance on the part of advisors to embrace annuities that seamlessly align with the RIA business model—and that assure the continuation of a client’s income—is very hard to understand. In the context of constrained investor retirees relying upon the advisor for income planning advice, I cannot see how adherence to an anti-annuity agenda doesn’t ultimately result in legal trouble for the fiduciary planner.

Identifying The Constrained Investor

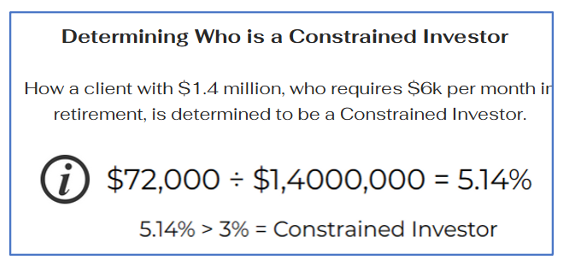

To determine if a client is a constrained investor, we use the income-to-assets ratio. Simply divide the income needed on an annual basis by the amount of money available to produce income. If the resulting percentage is 3%, or more, the client is a constrained investor.

Constrained Investors may own significant amounts of investment assets—$10 million or more. This can be surprising to advisors. With an assets-to-income ratio of 5.2%, a client with AUM of $20.6 million—who requires an income of $90,000/month—is very much a constrained investor. I site this example because it is a real case. A financial advisor who is affiliated with Advisor Group won management of the $20.6 million by using the constrained investor strategy.

The Fictitious ‘Safe Withdrawal Rate’

What is the meaning of “safe?” Mirriam-Webster defines this word as, “free from harm or loss.” I bet we can all agree on this definition…EXCEPT when it comes to portfolio withdrawals for retirement income. Once we cross the border into that dicey subject, the meaning of “safe” becomes variable over a wide spectrum of definitions, ranging from 5%, or more, all the way to my own assertion that the safe withdrawal rate is nothing but a fiction.

I believe I am correct in making this assertion because of a fatal flaw in each of the thousands of articles and papers that profess to define the safe withdrawal rate: All of them assume that the retiree never sells. I ask you, given the emotional makeup of retirement-age clients, and their tendency to become gripped by fear that causes them to want to sell securities during periods of market losses or extreme volatility, does the “never sell” assumption upon which safe withdrawal rate analyses are constructed align with your own experiences? Have you ever sold out of your own investment positions during such market conditions?

Would you not be in a better position—emotionally and financially—if you could say to the client:

“Look, Bob, I know you are nervous. But remember, your monthly paycheck is secure. And we’re not going to need the money in your third bucket for another six years. Don’t worry! Ride this out. The plan is working as designed You are on track.”’

The Misplaced Reliance Upon Monte Carlo Simulations

The then NASD’s sanctioning of Monte Carlo’s use with clients was a grave error, if for no other reason that it conveys to clients a false sense of security about the durability of their projected retirement income. If I had the power to do so I would ban its use with constrained investors.

Recent research by Massimo Young, CFA, and Wade Pfau, Ph.D. has once and for all exposed Monte Carlo for what it is: inconsistent, unscientific and prone to misleading both advisors and clients. Young and Pfau explain what you may well have personally experienced: feeling confident in telling your client that your proposed plan is “safe.” It’s likely not. Adding to the integral and flawed “never sell” assumption, Young and Pfau show that Monte Carlo projections rely heavily upon the capital markets assumptions (CMA) used.

Working with the CMAs used by 40 large investment firms, Young and Pfau identified widely ranging CMA inputs. For example, depending upon the firm, bond returns ranging from 2.542% to 5.82%, and stock returns ranging from 5.15 to 10.63%. What is the effect of this in practice? The same client, meeting with two different investment advisory firms, can be shown two wildly different probabilities of success: 95%, and 62%.

Even safe withdrawal rate experts can’t agree on what is “safe.” In a USA Today article published in May 2020, the originator of the 4% Rule, Bill Bengen, suggested that due to inflation and historically high equity valuations, retirees should reduce their withdrawals to a level below 4%. Five months later, Bergen’s view had changed, with him suggesting that the maximum safe withdrawal rate should be increased to 4.5%.

In November of 2021, Morningstar found that the safe withdrawal rate should be reduced to 3.3%. But in 2022, Morningstar, had a change of heart and increased the safe withdrawal rate to 3.8%.

In September 2022, researchers from the University of Arizona and University of Missouri published an academic paper that found that the safe withdrawal rate to be 2.26%.

Ten months earlier Barron’s had published an article that asked the question, “Forget the 4% Retirement Spending Rule. How Do You Feel About 1.9%?”

Think this is confusing to clients?

Look, I know that among some reading these words Monte Carlo simulations have become an article of faith. But let’s be honest and acknowledge the inconsistent and misleading nature of the approach. Clients’ retirement security is too important to leave to a “safe withdrawal rate” concept that is unsupported by science, disagreed upon by experts, variable depending upon from whom a client is looking to for advice, and is prone to conveying an unjustified sense of security.

If your client is “overfunded,” with ample spare liquid assets to account for unexpected reductions in his or her capacity to generate income from savings…then fine. The systematic withdrawal strategy is appropriate. But for the millions of America’s constrained investors, the use of systematic withdrawal strategies based upon Monte Carlo simulations is truly inappropriate.

The Long-Term Effect Of Monte Carlo On The Adoption Of Annuities By Investment Advisors

Slow adoption of annuities in the RIA channel is largely the byproduct of advisors’ use of Monte Carlo simulations. It’s time for this to change. The annuity industry certainly changed to accommodate the RIA business model.. Today’s annuities integrate seamlessly with RIAs’ portfolio management systems. They can be “wrapped” like any investment. Why hasn’t there been a rush among RIAs to adopt these products? Is a retiree client of an RIA less deserving of secure income than a client of an insurance agent? Of course not. But Monte Carlo has enabled the fiction of “safe” to drive advisors’ recommendations, as well as retirees’ acceptance of those recommendations. I fear this ends badly for some RIAs should the capital markets not perform well in the months ahead.

Because constrained investors must have longevity protection, when a financial advisor fails to recommend lifetime guaranteed income, the advisor's failure is reckless bordering on malpractice. I know that comes across as strong, but think of it in this context:

If your insurance agent failed to recommend that you purchase homeowner insurance, you would be supremely angry in the event your house burned down. You would surely sue the agent for professional malpractice. A retiree losing his or her retirement income is the financial equivalent of the retiree’s house burning down.

How Advisors Tend To Unintentionally Fail ‘Boomer’ Women Clients

The failure of systematic withdrawal plan to incorporate lifetime income protection leaves many women unprotected against longevity risk. Considering that women have longer life expectancies than men, this is an unconscionable failing. Research from Blackrock shows that the majority of "boomer" women are deeply concerned about outliving their income. Moreover, the markets-based approaches to income planning that many investment advisors rely upon are misaligned with the investing preferences and priorities that boomer women express to researchers. The plain truth is that men and women look at money differently.

Men tend to be concerned with historical investment performance and the process of individual stock picking. Women prioritize goals, risk-reduction and recognition of their values. They want to be listened to in the context of an authentic relationship with the financial advisor. When these dynamics are not present, in 70% of cases the woman responds by firing the financial advisor after her husband passes. Trillions in what I call "misaligned money,” retirement savings that is poorly planned in the context of women’s investing priorities, has created a massive business opportunity for advisors who understand how to properly plan retirement income for women.

Success In The Future Is As Easy as 1, 2, 3

I leave you with three thoughts.

1. In retirement it’s your income, not your savings, that creates your standard of living.

2. No retiree stops needing income.

3. Women live longer, are concerned about outliving their savings, and prioritize risk reduction.

Finally, withing five years, women will control virtually all available wealth assets—as much as $30 trillion. If you want to continue to be professionally successful, you’ll take to heart 1, 2 and 3.

Wealth2k Founder David Macchia is an entrepreneur, author, IP inventor and public speaker whose work involves improving the processes used in retirement income planning. Macchia is the developer of the widely used The Income for Life Model, and the recently introduced Women And Income. He is the author of two books, Constrained Investor, and Lucky Retiree: How to Create and Keep Your Retirement Income with The Income for Life Model.