Have we finally reached peak credit markets?

It’s a question that big names like BlackRock, DoubleLine and Pimco have been asking during this seemingly endless summer of debt.

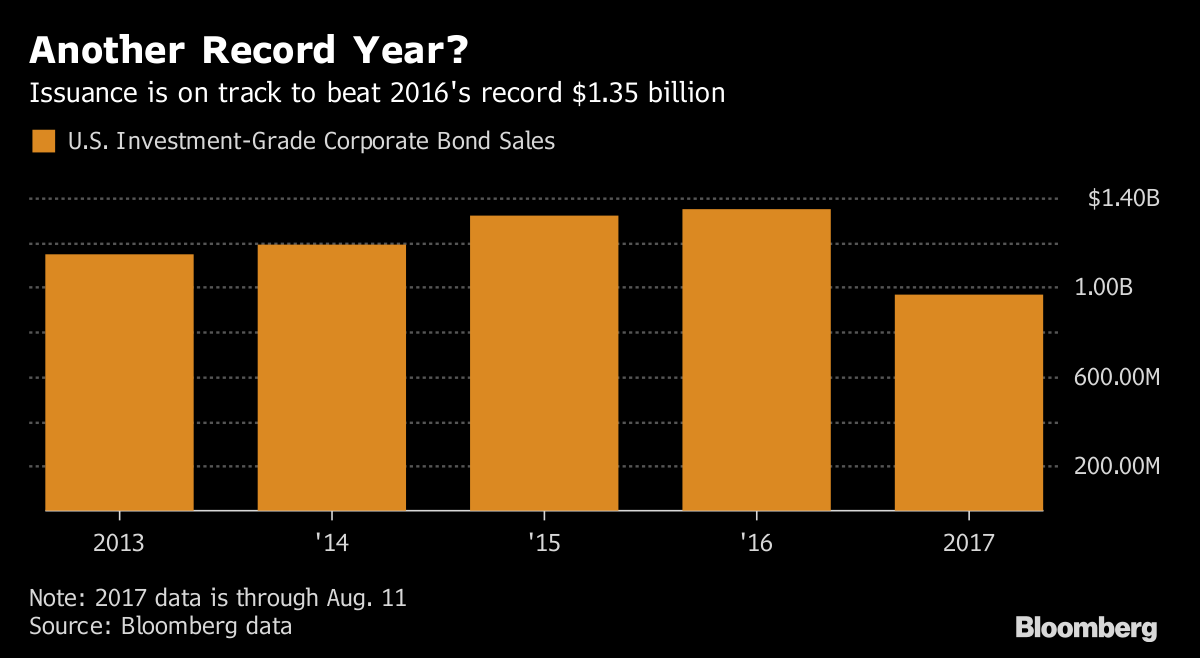

Signs of froth are everywhere. U.S. high-grade companies, which have already sold almost $1 trillion of bonds this year, are on track to break old issuance records. By some measures, corporate America is deeper in debt than ever before. Junk bonds, yielding on average just 5.8 percent, have fallen close to post-crisis lows.

And on Friday, investors lined up in droves to provide $1.8 billion in financing to Elon Musk’s unprofitable electric carmaker, Tesla Inc. -- and at interest rates that few could have envisioned a couple of years ago.

For Eaton Vance’s Kathleen Gaffney, it adds up to a market with all the hallmarks of a mishap waiting to happen.

“It can be hard to know the exact moment of a top but the signs are clearly there,” said Gaffney, who’s been buying and selling bonds for more than three decades, after starting her career at Loomis Sales & Co. “People are ignoring the fundamentals and taking a big leap of faith.”

Last week, there were indications that the 18-month long rally in junk bonds may finally be starting to end. Triggered by mounting tensions between the U.S. and North Korea, the notes slumped to their weakest level since April as Morgan Stanley flagged the beginnings of a correction.

The cost to protect the securities from default climbed to its highest level in about a month. BlackRock Inc., DoubleLine Capital and Pacific Investment Management Co., among others, have warned investors to pare back risk by reducing holdings of assets such as high-yield bonds and U.S. stocks.

Overlooking Flaws?

Granted, there have been plenty of instances over the past months when it seemed like the corporate bond market would finally come back to Earth. Yet time and again, demand has bounced back, as ultra-low interest rates around the world left bond investors with few higher-yielding options. Junk-debt investors are getting only about 3.9 percentage points of extra compensation compared with risk-free government debt, close to a post-crisis low.

And perhaps no case better illustrates the effervescence than Tesla. Investors overlooked its negative cash flow and repeated trips to capital markets to snap up its bonds, allowing the company to increase the size of the sale from the original $1.5 billion. It’s paying 5.3 percent on its new debt, a record low coupon for a bond of its rating and maturity.

“That Tesla could come to the market at a little over 5 percent yield for a low-single B rated company, is something of a sign of exuberance,” said Gene Tannuzzo, senior portfolio manager at Columbia Threadneedle, with about $467 billion under management. “Elon Musk is a pretty cool guy but they haven’t figured out how to make money yet and that’s not a lot of yield.”

Traces of froth are also starting to show up in M&A financing. Masayoshi Son’s SoftBank Group Corp., one of Japan’s most indebted companies, still was said to be able to line up as much as $65 billion in financing as it weighs a formal takeover offer for Charter Communications Inc. and looks to possibly merge it with Sprint Corp.

Charter already has $63 billion of debt on its balance sheet, while Sprint carries $40.9 billion. SoftBank has total debt of about $130 billion. Meanwhile, Son’s rival billionaire Patrick Drahi is working on his own potential offer to buy Charter, even though Charter’s market value is about double that of Drahi’s Altice NV and its U.S. unit combined.

Foreign Buyers

Demand for extra spread amid flat or negative rates brought overseas investors in droves to U.S. credit, helping prop up the borrowing desires of companies eager for the cheap debt. Even with all the angst surrounding North Korea, U.S. corporate high-yield funds had their second consecutive week of inflows in the week ended Aug. 9, Lipper data showed.

“The one thing we are watching is how much money is flowing into credit markets from outside the U.S.,” said Ken Monaghan, Amundi Pioneer Director of Global High Yield. “Those investors aren’t buying Treasury bonds anymore -- they’re buying corporate bonds, both investment grade and high yield. One of the things that concerns us is to what extent that money will depart when rates rise overseas.”

Elsewhere, there are signs risks are being overlooked. U.S. high-yield bonds sold in June contained the weakest protections for lenders of securities issued in any single month on record, according to a July 11 report from Moody’s Investors Service.

And overlooking it all is the pervasive niggle that comes with a growing debt pile. For all the indications of strain within, that shouldn’t be overlooked, according to Columbia Threadneedle’s Tannuzzo. Companies have sold $968 billion of investment-grade notes this year. Leverage ratios, a measure of debt to earnings, are near their highest since before the crisis for non-financial firms in the S&P 500.

“The thing you miss unless you step back: we’re just seeing a lot of issuance,” Tannuzzo said. “Valuations are very extended.”

This article was provided by Bloomberg News.