Karina Funk remembers when the concept of a connection between profits and responsible corporate practices was just beginning to take shape. “Early in my investment career I heard more than once that you can either make money with stocks or save the planet, but you couldn’t do both,” says the 47-year-old manager of the Brown Advisory Sustainable Growth Fund.

Today, with many investors in the U.S. and abroad integrating sustainability into investment decisions, that opinion has largely been shelved. In 2019, the estimated net flows into open-end and exchange-traded sustainable funds available to U.S. investors totaled $21.4 billion for the year, according to Morningstar. That’s nearly four times the previous annual record for net flows set in 2018.

“With growing investor interest in sustainable investing, especially among younger investors, 2019’s flows may be the leading edge of a huge wave of assets to come,” noted Morningstar analyst Jon Hale in a recent report.

To be clear, sustainable investing isn’t just about screening out “sin stocks” or investing heavily in alternative energy companies. It’s a more encompassing approach that looks for positive environmental, social and governance (ESG) practices among a wide variety of companies throughout the economy. Proponents believe such characteristics help companies control risk because they can avoid penalties for environmental missteps and other infractions, and they can also eliminate or reduce expensive inefficiencies.

Leveraging superior ESG practices in a business can help raise revenues, cut costs and increase competitiveness. “We like to see companies that are using good ESG practices to control risk as well as create business opportunities,” says Funk, who has mined this space for well over a decade.

Like the broader universe of investment managers that highlight sustainability practices, Brown Advisory has seen ample inflows over the last 18 months into its large-cap growth portfolio. Funk says about half of the money coming in is from investors with a sustainability mandate in mind. The remainder is from those just looking for a solid large-cap growth strategy with strong performance from a diversified portfolio of high-quality companies. Sustainability should not be pit against business fundamentals, she says. “For us, a sustainability strategy needs to go hand in hand with having strong fundamentals and adding shareholder value.”

American Tower Over Apple

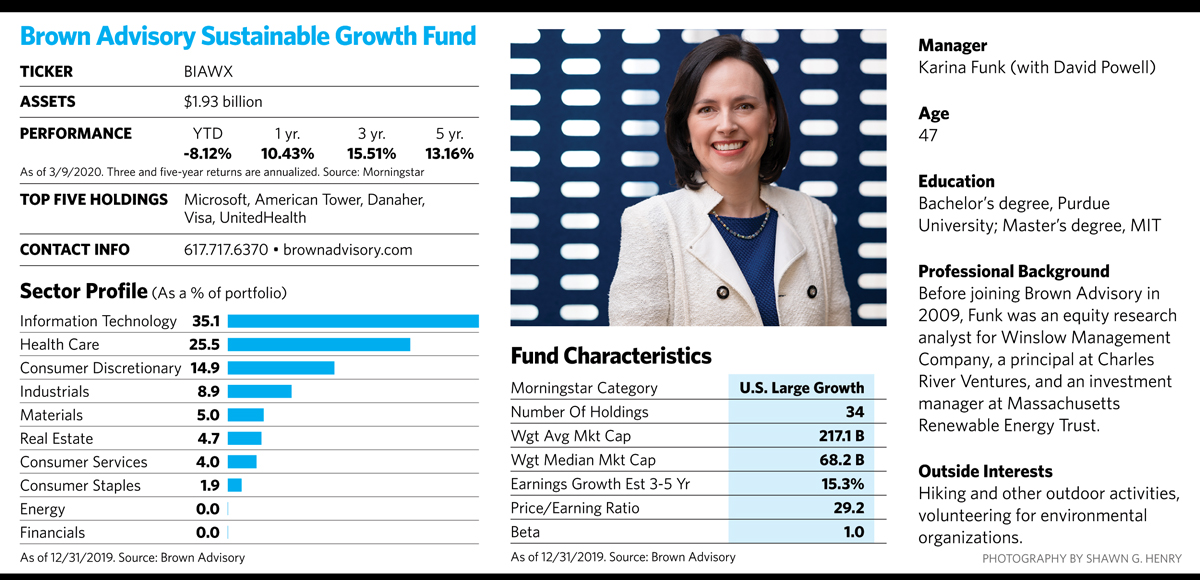

The fund’s concentrated portfolio of just 34 stocks differs from the benchmark in a number of respects. Its weighted median market capitalization is $68 billion, whereas the figure is $141 billion in the Russell 1000 Growth Index, demonstrating the managers’ willingness to dip into less familiar names: Several high-profile companies that dominate the market-cap-weighted benchmark are either absent from the fund or have a much smaller weighting.

That weighting, however, hurt the fund’s performance in the last three months of 2019, when Apple, which has a nearly 9% weighting in the index but no presence in the Brown Advisory fund, rebounded sharply.

Funk says the fund swapped out of Apple in the fall of 2015 to upgrade into American Tower, the second-largest wireless tower operator in the U.S. At the time, Apple was just entering the iPhone 6s and iPad Pro product cycles, and given the number of variables driving the company’s growth, there were a wide range of outcomes for the company both on the upside and downside. Meanwhile, American Tower had a clearer path forward because of its long-term service contracts and other factors. It is the only tower operator to offer shared backup power-generating capacity for multiple carriers on its towers, and has been aggressively reducing its use of fossil fuels. While both stocks have done well since then, American Tower has experienced much less volatility.

So even with fewer of the mega-stocks that often drive performance, the fund has benefited from being different, beating the benchmark performance over the long term with less volatility. From its inception in June 2012 through last year, the fund’s Investor class shares saw an average annual return of 16.87%, while the benchmark saw 16.4%. The fund also beat the bogey’s annualized return by 1.2% over three years, and 1.87% over five years.

Over the years, Funk and co-manager David Powell have differentiated the portfolio by combining familiar growth names, such as Microsoft, Alphabet and Amazon, with less well-known companies that aren’t on many investors’ radar screens. Many of the latter group are solid, steady growers.

Ball Corporation, the world’s largest producer of aluminum cans, fits into that category. Unlike plastic, aluminum is infinitely recyclable. It’s also lighter weight, easier to recycle than glass, and uses less water in the process. Funk says Ball, which has consistently delivered mid-single-digit revenue growth and low-teens earnings growth per share, is in a good position to take market share from both plastics and glass packaging manufacturers.

Recent additions to the portfolio include Bio-Rad Laboratories, a globally diversified manufacturer of life science and clinical diagnostic instruments, software and services. Its technology is used for early diagnosis of disease, notably in oncology. Bio-Rad also provides products used in food and water safety testing, as well as quality control to improve laboratory performance.

Another recent addition, Nike, has been in the portfolio in the past. “We believe this is a great time to own it again because for the first time in recent memory, the company should be able to grow revenue and margins simultaneously,” says Funk. Nike’s increased shift to direct-to-consumer sales, cost reductions and pricing power should help improve margins while a new product mix and gains in market share have the potential to boost revenue. Even though the company has a new CEO and could use some improvement on the ESG front, Funk believes Nike “has evolved from approaching sustainability as reputation management to a more proactive view of sustainability as a source of innovation and growth.”

An Evolving Label

Funk’s introduction to the connection between responsible business practices and profits came when she was an undergraduate chemical engineering major in the 1990s doing a summer internship at a paper recycling plant. Her work on a project to conserve water during the recycling process sparked the realization that by saving water the company was also boosting its bottom line.

Funk’s first job out of college was working as an environmental engineer helping large industrial companies comply with emissions regulations. She got a rude awakening. “I was the last person any shift manager or business leader wanted to see or spend time with,” she recalled in a 2015 TEDx Talk. “I was nothing but a cost sink.” After working at investment consulting, venture capital and institutional investment firms in environmental evaluation, she joined green-centered Winslow Management Company in 2007. That company was later acquired by Brown Advisory in 2009.

Despite being an early ESG adopter, Funk admits the label is still evolving. A sustainable investing style isn’t as specific or readily definable as, say, investing in a specific sector, or in growth or value stocks. Those who employ it often use different yardsticks for sustainability, or put a higher value on one measure than another. A company that one analyst considers sustainable may get the thumbs-down by another.

To add to the confusion, a growing number of investment companies, including Vanguard and BlackRock, now incorporate ESG criteria into their investment process without specifically labeling their products as “sustainable.” With so many players on board, it could be argued that the increasing reach of ESG criteria into mainstream investing lessens the need for mutual funds that put sustainability in the forefront of their profiles.

Funk says that, like credit ratings, ESG ratings are a subjective evaluation that does not fit a “one size fits all” criteria. Some screeners prioritize a target company’s transparency and disclosure, while others look more at a company’s environmental or social track record. Investors need to look at what’s behind third-party ESG ratings to decide which ones align most with their priorities. “Ratings, whether you’re looking at mutual fund rankings, credit ratings or ESG grades, should not be viewed as an end point,” she says. “We look at them as a launch point for research that spurs subsequent questions and more digging for information.”

She adds that unlike many investment managers who incorporate sustainability into their evaluations, her firm puts them front and center. “We were doing this long before third-party sustainability ratings and standardization criteria came into effect,” she says. “For us, sustainability is not just an overlay or an add-on. We turn over more rocks and dig deeper to find out how a company’s strategy, operations and prospects for growth connect with its sustainability practices.”