For most of the last 40 years, the United States, like most developed economies, has suffered from a lack of demand for goods and services. This has contributed to a steady slide in inflation. More importantly, it has indirectly triggered recessions by funneling money towards assets, feeding bubbles, which have inevitably burst. A lack of aggregate demand has also slowed the recovery from those downturns, inflicting hardship on millions of workers and small business owners.

The causes of this lack of demand are not hard to deduce. Nor is it difficult to see how to remedy the problem, via changes in the tax code, exchange rate policy and government spending. However, these changes require tough political decisions and we seem to live in a democracy, which has run to populist seed, preventing us from confronting problems in a mature way.

In the absence of such mature decisions, politicians have reached out for easy solutions. Modern Monetary Theory (or MMT for short), is a set of ideas that has come into prominence in recent years, appearing to provide just such an answer by promoting the idea that budget deficits can largely be expanded without consequences. (The best-known proponent of Modern Monetary Theory, Stephanie Kelton, outlines these ideas in The Deficit Myth: Modern Monetary Theory and the Birth of the People’s Economy, June 2020.)

However, there is a problem with MMT. It essentially exploits the trust that people place in fiat currency and the financial assets denominated in them—namely, the idea that a dollar is a safe and reliable store of value. The more successful MMT is in pushing the economy towards full employment, the more likely it is that that trust will be undermined and eventually broken. Moreover, trust in money is much like trust in marital fidelity—once lost, it is exceedingly hard to regain.

We have today, without acknowledging it, already embarked on the MMT experiment. That makes it particularly important that we understand the nature of our macroeconomic difficulties, and the problem with using the opium of MMT to treat the injury of insufficient demand.

The Long Drift Down In Inflation

The formative years of my economics education were the early 1980s when economics, as a profession, was obsessed with inflation. Long a minor problem, it exploded in the 1970s, sparked by oil price spikes and fueled by surging demand from baby-boomers establishing households and loose monetary policy from over-indulgent central banks. The year-over-year CPI inflation rate soared, even in the midst of a deep recession, to 12.2% by the end of 1974, retreated, and then climbed again to a modern-day record of 14.6% in the spring of 1980.

The disruption caused by inflation gave a strong platform to monetarist economists, such as Milton Friedman, who argued that inflation was the result of too much government spending and too little discipline in controlling the growth of the money supply. It led to a political swing to the right, in the election of Ronald Reagan, and empowered the Federal Reserve, under the leadership of Paul Volker, to raise interest rates and tighten the growth in the money supply to reduce inflation.

Inflation did fall, particularly during and following the deep recession of 1982. However, even after the economy had regained its health, inflation continued to drift down, declining both during and following the recessions of 1990-91, 2001 and 2007-2009. Moreover, after each of those recessions, the recovery in economic activity was remarkably sluggish, causing many to wonder why demand wasn’t strong enough to produce faster recoveries or prevent this steady decline in inflation.

The Lack Of Aggregate Demand: Understanding The Causes

With the benefit of hindsight, the reasons for insufficient demand are clear enough. To see them, a good place to start is with the plumbing diagram that graces the opening pages of most introductory macroeconomics textbooks.

An economy that produces $100 in output of goods and services will also produce $100 in income that can be used to buy them. This is the wages paid to workers, rents paid to landlords and the dividends and interest payments paid to owners and lenders for their contribution to the production of that output.

Some of this great river of income leaks out of the system, of course. Some gets spent on imports, or is saved, or is taxed by governments. However, this lost demand is offset by other demand, from foreigners buying our exports, businesses investing in new plant and equipment and governments spending both on on-going operations and building new infrastructure. In a balanced system, this extra demand equals the amount that leaked out of the system. However, since the mid-1980s, the economy has frequently struggled with inadequate demand.

One part of the problem has been a too-high U.S. dollar, which has contributed to chronic trade deficits. Indeed, since 1980, the U.S. has had an average trade deficit of 2.6% of GDP and has failed to run a trade surplus in even one year. If we are buying substantially more of everyone else’s stuff than they are buying of ours, we are, right away, liable to see insufficient demand for the goods and services we produce.

However, a second major cause has been rising income inequality. According to data compiled by Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez, from 1951 to 1981, the share of income received by the top 10% of households was remarkably steady, averaging about 34% of the total. (See “Income Inequality in the United States, 1913-1998”, by Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(1), 2003, with data updated to 2018 on the website of Emmanuel Saez.) However, since then it has soared, exceeding 50% for the first time in at least a century in both 2017 and 2018.

The reason this is such a potent macro-economic issue is that better-off households tend to spend much less of their income on goods and services. Indeed, in 2019, according to the Consumer Expenditure Survey, the richest 10% of households spent just 64% of their after-tax income and saved the rest. The other 90% of households, on average, spent 99% of their income, many of them, of course, borrowing to finance spending. The steady growth in the income share of the richest households has contributed, simultaneously, to strong and rising demand for financial assets and lackluster demand for goods and services.

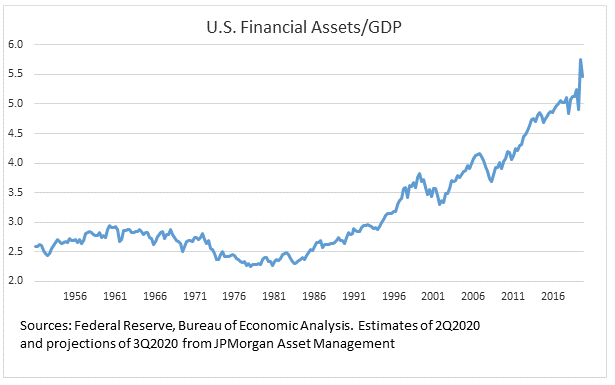

As an important aside, this can also, of course, partly explain some of the surges in asset prices in recent decades, which have occasionally ended in tears, as in the case of the tech bubble that ended in 2000 or the housing bubble that ended in 2007. Nor has this trend come to an end. Indeed, since the mid-1980s, the growth in asset prices has very consistently outpaced the growth in consumer prices. Consequently, the ratio of the value of U.S. financial assets to U.S. GDP has risen from an average of 2.6 times between 1951 and 1985 to roughly 5.5 times today.

The Lack Of Aggregate Demand: The Right Remedies

Over the years, the Federal Reserve has tried to remedy this lack of demand for goods and services by running a persistently easy monetary policy. However, as we have often argued in the past, cutting interest rates from very low levels is, at best, ineffective and, at worst, counterproductive, if you are trying to boost aggregate demand. While such rate cuts can make investment spending look more profitable, they also undermine confidence and reduce consumer interest income in a way that hurts consumer spending and thus negates their effects.

A more effective solution would start with a coordinated approach between the Federal Reserve and the Federal Government to lower the U.S. dollar exchange rate to levels consistent with trade balance. A second part of a solution would be to encourage more balanced spending across U.S. households. One way this could be achieved would be by raising taxes on the rich to fund lower taxes for poorer or middle income households as well as adopting a higher minimum wage and a stronger social safety net so people did not feel so obligated to save for old age or a potential health problem. Importantly, all of this could be achieved without flooding the economy with liquidity or running massive federal deficits. However, it would require tough political choices.

The MMT Solution

The allure of Modern Monetary Theory is that it seems to imply that these choices don’t, in fact, have to be made.

MMT starts with a logical truism, namely that a sovereign government, in control of a sovereign central bank, can never be forced to default on its own currency debt. This being the case, in an economy where there is a lack of aggregate demand, a government can just ramp up government spending or cut taxes to remedy the situation. As the deficit rises, the central bank can buy more of the government debt to prevent any increase in long-term interest rates. MMT argues that there isn’t any problem with this until inflation appears. If inflation does crop up, the government can just raise taxes to quell demand.

Provided it has a light touch on both the gas and the brake, the economy can emerge from recessions faster and hover at close to full employment for longer. Indeed, just to make sure that full employment is sustained, the advocates of MMT also suggest that part of this deficit spending could be devoted to providing a job guarantee for everyone that wanted to work, with the government hiring those the private sector won’t.

MMT In Practice

While MMT may seem like a purely theoretical construct, it should be recognized that many governments, including the U.S. government, are effectively already putting MMT into practice.

After years of fiscal restraint, Congress passed the Tax Act of 2017, even when the economy was close to full employment, leading to a sharp widening of the Federal deficit in 2018. This year has, of course, seen a much more significant increase in the deficit in reaction to the social distancing recession with the federal debt rising from 79% of GDP this time last year to likely over 105% of GDP next year.

The Federal Reserve, while ostensibly engaging in QE to hold long-term interest rates in check has, in practice been monetizing the debt, ensuring that, at least for now, the federal government can run a huge deficit, financed at very low interest rates. Indeed, since the start of the year, while the federal government has added an astonishing $3.7 trillion to the federal government debt, the Federal Reserve has increased their Treasury holdings by almost $2.1 trillion, financing more than half of the additional debt.

It should be noted that since all the profits earned by the Federal Reserve on its portfolio are paid to the Treasury, this is essentially an interest free loan. It should also be noted that to achieve this increase in assets, the Fed has also permitted an enormous increase in its reserves, which has, in turn, led to a huge surge in the money supply, with M2 growing by more than $3 trillion, or 21% since the start of the year.

The Problem With MMT

The danger, of course, is that this could all end very badly. For as long as inflation remains low, there seems little cost to this massive increase in the money supply or in total financial assets.

However, the problem is that each dollar of the money stock, and indeed of financial assets in general is, essentially, a coupon, entitling the bearer to some share of the goods and services produced by the U.S. economy. If I have money in a bank account or a mutual fund, I didn’t accumulate it just to look at the pretty numbers. I assume that, at a time of my choosing, I can cash in these assets for some goods and services.

The danger in the rapid expansion of these financial assets, which MMT would only accelerate, is that there could easily come a time when the holders of those coupons begin to notice how many more coupons are floating around, and begin to worry that they won’t be able to redeem them for as many goods and services as they thought. This could cause more people to try to convert these coupons into assets of more security.

Holders of small cap growth stocks might decide that large-cap value stocks or bonds were a safer bet. Holders of long-term bonds might worry about an inevitable rise in interest rates and seek greater security in cash. And holders of cash might decide that real assets such as real estate or commodities or even foreign currencies managed in a more responsible manner would be a better bet. If, of course, this were to cause rising commodity prices, rising money velocity or a falling dollar, it would add to the inflation problem. It is also not clear that the government would have the intestinal fortitude to raise taxes in this environment, as MMT would recommend, or have any clue how much to raise them to restore faith in the currency and financial assets.

Moreover, there is no reason to believe that this would all happen gently. If investors and consumers suddenly began to expect higher inflation, interest rates could rise sharply both because of an increase in expected inflation and uncertainty about how much that inflation could be in the future. Many of the economies of Latin America provide a contemporary and stark warning about what can happen to an economy when people lose faith in its money.

It should be emphasized that there is nothing imminent or inevitable about this outcome. Inflation is very unlikely to spiral higher 2020 or 2021 in an economy of still high unemployment. Moreover, responsible fiscal and monetary policy in the aftermath of the 2020 elections should probably still be able to alleviate the situation.

However, for investors, it is important to consider how to protect themselves if such policies are not adopted and we find ourselves, within a few years, in new paradigm, where, in sharp contrast to the last few decades, inflation trends up and many financial asset prices trend down.

David Kelly is chief global strategist at JPMorgan Funds.