There’s no denying that longevity is increasing in the U.S. and throughout much of the world. Recent legislation like the SECURE Act, passed on May 23 by the House of Representatives, is beginning to recognize this trend and the potentially far-reaching implications on society. One much-publicized provision of this bill is a proposed delay in the required-minimum-distribution (RMD) age from 70½ to 72. The bill also proposes a change that would allow IRA contributions for all workers with earned income, regardless of their age, along with rules requiring employers to allow long-term part-time workers to participate in company 401(k) plans. These changes are driven, in part, by expectations that greater longevity will result in more workers choosing and needing to remain employed beyond age 70.

A potentially negative consequence of the bill (as currently proposed) is limiting the “stretch IRA” provisions to 10 years if an IRA is inherited from a parent or spouse. These changes are likely to impact clients’ financial plans and strategies for transferring family wealth. The bill’s recognition of greater longevity also begs the question, “How can financial advice better incorporate longevity risk planning in ways that are meaningful to clients?”

As the Senate debates the SECURE Act, let’s examine some of the potential financial planning implications of longer lives and suggest ways to quantify and communicate potential risk to clients. Our goal is to inspire advisors to ask what actions to consider in response to the greater longevity we’re witnessing among clients and in society as a whole.

Bearing Vs. Sharing Longevity Risk

One of the more obvious challenges we face in retirement planning is that individuals are increasingly required to bear longevity risk. Previous generations enjoyed having longevity risk largely covered (or at least shared) with employers via lifetime income benefits from defined benefit plans. Today’s workers usually are not so fortunate. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, as of March 2018, on average, only 3% of full-time private-industry workers had access to a defined benefit plan. In comparison, 58% of these same workers only had access to a defined contribution plan. These figures show just how widespread the longevity risk shift is and the importance of our role in helping clients manage that risk to create sustainable retirement income plans.

While the decline in defined benefit plans has been accompanied by greater access to defined contribution plans, like 401(k)s, there is little evidence that these new plans are adequate replacements. First, maximizing contributions can be challenging, especially given that workers face increased basic living costs, including higher housing and health-insurance expenditures. A study by MIT AgeLab showed 35% of student loan balances were held by individuals over age 40. Higher living costs and debt levels challenge employees’ ability to contribute up to the full legal limit of the defined contribution plan. Even if they can contribute the maximum amounts, many are challenged to accumulate enough outside those plans to adequately cover their longevity risk.

Workers’ retirement account values also face greater market risk, both while they’re working and throughout a potentially much longer period of retirement. Consider a retirement that lasts only 20 years (say for a person’s life from age 65 to 85). It’s reasonable for investors to expect two or three bear markets during that period. That means the risk of losses or of getting shaken out of the markets is very real, perhaps even more so if the retirees don’t have the benefit of expert investment management to manage through down cycles. This risk is exacerbated by the very real prospects for lower capital market assumptions over the next several years.

“Grey Divorce,” New Spouses

Another result of people living longer is the increase in the number of “grey divorces.” While we may be living longer, some marriages aren’t lasting over couples’ extended life spans. The increased rate of divorce for individuals over age 50 reflects the decreased stigma in splitting, as well as the greater health and increasing economic independence enjoyed by women in this age group.

Increasingly, even long marriages are at risk. “Among all adults 50 and older who divorced in the past year, about a third (34%) had been in their prior marriage for at least 30 years, including about one in 10 (12%) who had been married for 40 years or more,” says a 2017 Pew Research Center report. “Research indicates that many later-life divorcées have grown unsatisfied with their marriages over the years and are seeking opportunities to pursue their own interests and independence for the remaining years of their lives.”

It seems reasonable that as people live longer, we’re likely to see even more couples deciding to split much later in life, possibly during their retirement years. Consider a couple who carefully save for retirement, transition to a long-imagined lifestyle and then decide to part ways. If years of financial decisions such as retirement timing, asset titling and spending budgets have been established during a long marriage, a grey divorce can upend even the most prudent retirement planning decisions.

Those divorcing late in life may also likely find new spouses, and that creates planning challenges for those wanting to protect assets and create estate plans that balance the new spouse’s needs with those of existing heirs. If the new spouse is younger, the couple will likely need a larger asset base to offer a longer period of cash flow and portfolio longevity. This challenge is compounded when assets or income sources have been partially dissipated in a divorce. At a minimum, advisors should provide detailed analyses of potential retirement spending early in the new relationship. That way, both parties are clear about the financial, lifestyle and potential estate plan implications of taking on a new spouse.

Analyzing Potential Delays Or Dissipation Of Inheritances

Clients can also be affected by the greater longevity of their parents and the effect that has on the transition of family wealth. Inheritances may be delayed or assets may be dissipated if aging parents incur significant health-care costs. Or parents may simply live longer, which could delay heirs’ access to the assets. Owners of lucrative family businesses may elect to stay in the businesses longer, deferring transfer of income production or the ultimate wealth transfer to heirs.

For those baby boomers anticipating for years that an inheritance will cover their own longevity risk, a delay or loss of inheritance could be a rude awakening. While it’s difficult to quantify, parents’ prospects of living a longer life may reduce the likelihood that they will, while still alive, make significant gifts to their children. Imagine the potential impact on their retirement lifestyle if the announcement of lower lifetime gifts, or reduced or eliminated inheritance, comes later in clients’ life cycles—when it may be too late to replace the lost inflow of those expected assets.

Potential Responses

One way for retirees to manage their longevity risk is to turn to insurance products, which allow users to share that risk with an insurance company. This topic warrants an article all its own, so suffice it to say that products like hybrid long-term-care policies are just one example of a range of products aimed at off-loading some longevity risk. Insurance products may also be helpful tools in grey divorces to provide for newly single women or for prenuptial arrangements or to provide assets for children or a new spouse.

If clients are focused on paying unexpectedly high costs for care at the end of their lives, margin or other debt lines can be another tool. Consider, for example, an only child who needs cash flow to support his father’s care needs. It may be useful to utilize a margin line on the son’s taxable investments to create cash for care expenses. Using margin saves the father from paying capital gains taxes on potentially low-basis assets. The father’s estate plan could be revised to incorporate a provision to pay back any margin loan his son incurred, thereby replenishing the son’s asset base. Additional potential tax savings may be realized if the son receives a stepped-up basis on inherited assets upon his father’s death.

Beyond these approaches, we suggest using technology to help quantify and shed light on longevity risk for each specific client. The goal is to provide the advisor and clients with opportunities to ponder how longevity risks could derail an otherwise solid plan. The process is also a way to start a conversation with clients about reviewing their insurance, working longer or adjusting spending budgets as ways to secure their plan in the face of longevity risks.

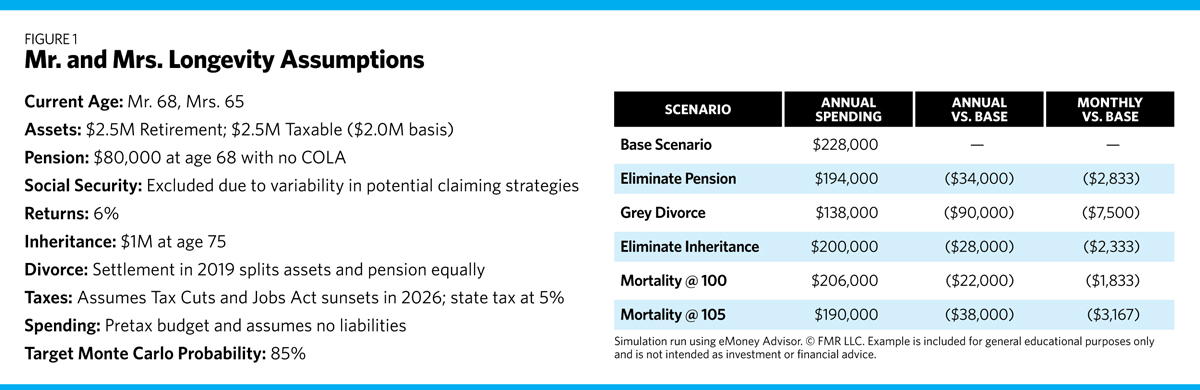

In the chart, we illustrate potential impacts that longevity-related risks could have on annual and monthly retirement spending budgets. As you’d expect, the impact of a grey divorce creates the greatest reduction in potential annual spending. Consider the effect it could have if a client also takes on a second spouse who has little or no assets. In the case where a couple does not receive an expected $1 million inheritance, their “safe” monthly spending budget would be reduced by an estimated $2,333 each and every month of a 30-year retirement. It’s also significant to note that a person who lived to age 105 would reduce guideline annual spending by $38,000 per year from $228,000 to $190,000. The goal here is not to focus on the precise numbers but rather to display, in directional terms, how much clients may want to reduce current expenditures in order to provide a longevity safety net. To the extent more than one of these events occurs, the financial impacts compound. Running plans for younger clients may introduce even greater variability between the model and actual outcomes since there is a greater likelihood of any given event over time plus less certainty about exactly how much longevity could improve for younger generations.

Conclusion

As advisors, it’s our responsibility to spot trends in the lives of our clients and to develop and provide tools and solutions for managing the numerous risks life can deliver, including longevity risk. We must continue to work together in our industry to identify trends and provide solid, practical solutions for clients and families who depend on our foresight and ability to both protect them from longevity risk and help them build the wealth required to enjoy the longer lives they (and their parents) are likely to live.

Dawn Doebler, MBA, CPA, CFP, CDFA, is a principal and senior wealth advisor at The Colony Group. Michael J. Nathanson, JD, LLM, is chairman and chief executive officer of The Colony Group.