Relatively speaking, value investing was the place to be for equities in 2022. Sure, most value-oriented indexes experienced single-digit losses, but that was significantly better than the double-digit losses suffered by both growth-oriented and broad-category indexes. The outperformance followed a long period of value’s underperformance after the Great Recession as historically low interest rates and accommodative monetary policies helped propel growth stocks into the stratosphere and, conversely, made value investing an uncool and less profitable place to be.

But as the Federal Reserve’s bruising regimen of interest rate hikes last year took the starch out of pricey—and in some cases speculative—growth stocks, it prompted investors to gravitate toward less-buzzy stocks of companies with stable earnings, sound balance sheets and reasonable valuations. And many pundits believe the rebound in value stocks has room to run.

The folks at asset manager Hotchkis & Wiley don’t pay much attention to the debate about growth versus value investing. They’re all-in on the value side, and have been since the Los Angeles-based firm was founded in 1980. The company offers nine value equity mutual funds covering domestic and international markets, along with a high-yield bond fund. Through the years, its staff of long-tenured analysts and portfolio managers have navigated the tech bubble of the late 1990s, the financial crisis of 2007-2009, and the pandemic of 2020. And through it all they haven’t changed their tune.

“Our firm has gone through all of these cycles and have come out stronger both from an investment perspective and in terms of our process and the execution of our portfolios,” says Jim Miles, co-portfolio manager of the Hotchkis & Wiley Small Cap Value Fund. “Our focus on value has never changed.”

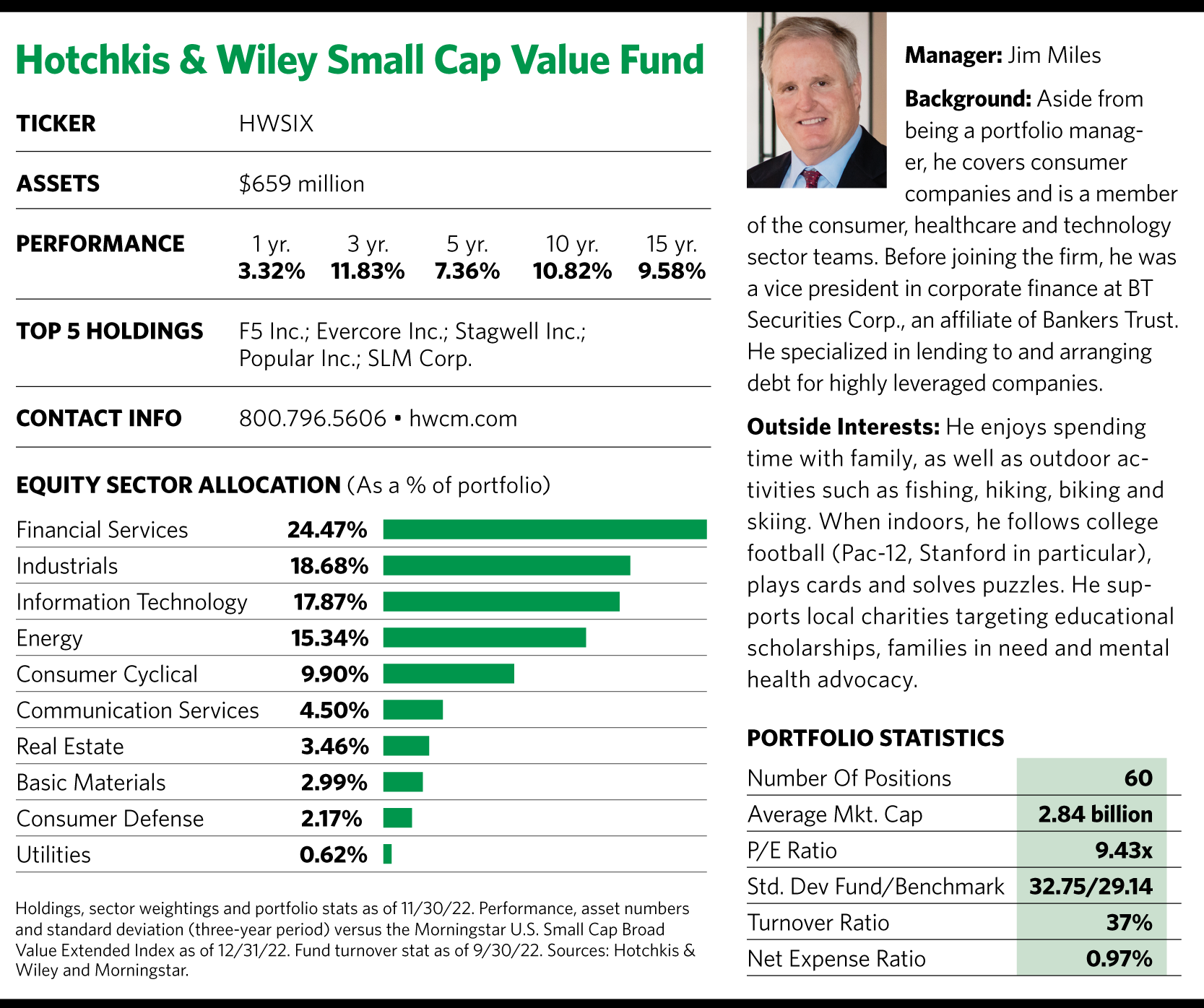

Value investing has had its ups and downs through the years, but the Small Cap Value Fund has been a consistently solid performer within its category thanks to the steady leadership of Miles, who took the fund’s reins in 1995, and his partner, David Green, who became co-manager 1997. According to Morningstar, the fund has been a top-quartile performer within its small-value category for each measurable period from one year to 15 years. In 2022 it was the third-ranked fund out of 468 in the category on the strength of its 3% return. And over the past 15 years it ranked third out of 226 funds, with average annualized returns of about 10%.

But it hasn’t always been a smooth ride. For example, there were consecutive years in the 2010s when the fund placed in the bottom quartile.

“If you look at our track record, and David and I have managed this strategy together for 25 years, you can see some short-term volatility, but ultimately the long-term returns are attractive. And when you compound that, a dollar given to us when we first started managing is worth $15 today. If you invested in our benchmark, it would be worth half that much,” claims Miles, referring to the Russell 2000 Value Index.

In a report last year, Morningstar analyst Christopher Franz said the Small Cap Value Fund’s “contrarian profile isn’t for the faint of heart but should reward investors who are aware of its risks.” He added that the fund managers focus on buying deeply out-of-favor companies and are willing to endure short-term pain.

Miles takes exception with Morningstar’s assessment. He notes that Hotchkis & Wiley’s client base consists primarily of institutional and retirement-oriented investors with horizons stretching out many years or decades. As he puts it, his clients are less worried about short-term volatility and more focused on the fund producing long-term returns that achieve their investment objective over, say, a 10-year time horizon. He points to studies showing that the value factor plays the biggest role in generating positive returns over a 10-year period.

“The lower the valuation your portfolio is, the higher the return is in the subsequent 10-year period,” he says.

Valuation Winds

Miles and Green are bottom-up managers who screen the small-cap universe and target the bottom 40% of companies that look inexpensive given their normalized earnings, which Miles describes as long-term sustainable economic earnings. From there, the two managers work with the firm’s deep bench of investment analysts to assess companies by looking for certain qualities.

The first is business quality. “We think of a high-quality business as one that generates returns greater than the cost of capital and grows faster than the economy and can do that over a long time period,” Miles says.

The analysts also parse the balance sheets and corporate governance attributes of potential portfolio holdings. The end result is a portfolio constructed one stock at a time regardless of sector weightings. And depending on which way the valuation winds blow, that can make the fund look very different from its benchmark.

For example, Miles noted, the fund had virtually no technology exposure during the tech bubble of the late ’90s. Yet recently, it was overweight in technology. The fund was also recently more exposed to the energy and industrial sectors than its benchmark. On the flip side, the fund was significantly underweight in healthcare (it had zero exposure), a sector many investment strategies have hailed as one of the best opportunities during the current market downturn but which Miles thinks of as a crowded and expensive trade.

“So it depends on what the market is saying is attractively valued,” Miles explains. “That can lead to portfolios that in the view of Morningstar look contrarian. But in our view, it’s not so much contrarian but instead is aligning with valuation, knowing that valuation is the one factor that delivers on long-term return.”

But finding value-oriented investments is more than just scrounging the bargain bin section for off-price items. Miles notes there are a host of things that could depress earnings in the short run, and a focus on short-term earnings can lead to a deceptively low multiple. “The key thing is you need to make sure the company has the financial strength and balance sheet and the liquidity to make it through whatever this transition period is,” he says.

“There are a lot of stocks that are statistically cheap, but there’s been a structural change in demand for their products or services, and as a result of that change it’s unlikely they’ll get back to their historical level of performance,” he adds. “We view those as value traps.”

Room To Run

Miles points to Fluor Corp. as an example of his and Green’s investment thinking. Fluor is an engineering and construction company involved in large, complex projects such as refineries and liquid natural gas projects, along with civil engineering projects such as bridges and highways. Its share price was in sharp decline from late 2018 through the pandemic. Part of the problem, Miles says, was that Fluor was saddled with fixed-priced contracts and its cost overruns ultimately depressed earnings.

But he noted that key competitors were exiting the business, and that the company shifted away from fixed-price transactions primarily to “cost-plus business,” in which expenses are estimated up front but the final price is calculated at a project’s completion.

“Investors will eventually realize the volatility of earnings will be less, but for now the market doesn’t see the long-term outlook for this company and it’s trading at a very low multiple,” Miles says.

Fluor’s stock rose 40% last year, aided by demand for LNG terminals to bring natural gas to Europe, where supply became a problem after Russia invaded Ukraine. Miles says Fluor formerly was a top-10 holding in his fund and it remains a core holding, but its weighting was recently reduced as the stock jumped 117% during the past two years.

As stalwart value investors, the Hotchkis & Wiley managers are attuned to the ebbs and flows of market cycles. And that’s why Miles is excited about the outlook for value investing. He believes the markets are undergoing a regime change, and he reminds investors that value’s past periods of weakness have been followed by periods when it shines.

“Given the underperformance we’ve had the past decade, you could easily see a value cycle of five to seven years,” he says. “We’re nowhere done with it if you look at history being a predictor of the future.”