It’s easy to sense signs of strain in the U.S. economy: inversion of the yield curve, lackluster jobs data and an escalating trade war with China. It’s more difficult to gauge when a slowdown turns into a recession. Predicting its severity—mild or monstrous?—is even more difficult.

Recent research by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis suggests that real yields on 10-year Treasury bonds are the key to answering this question.

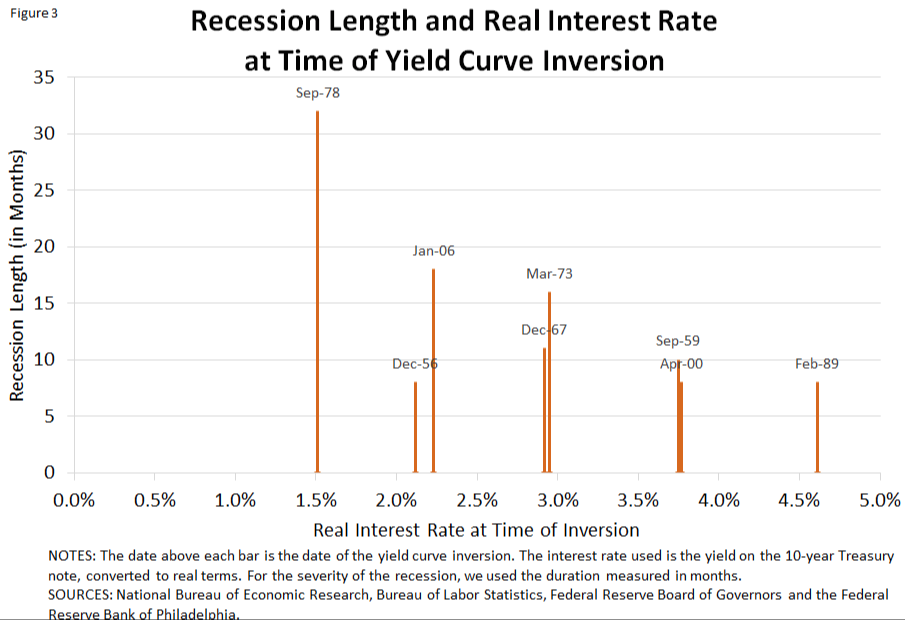

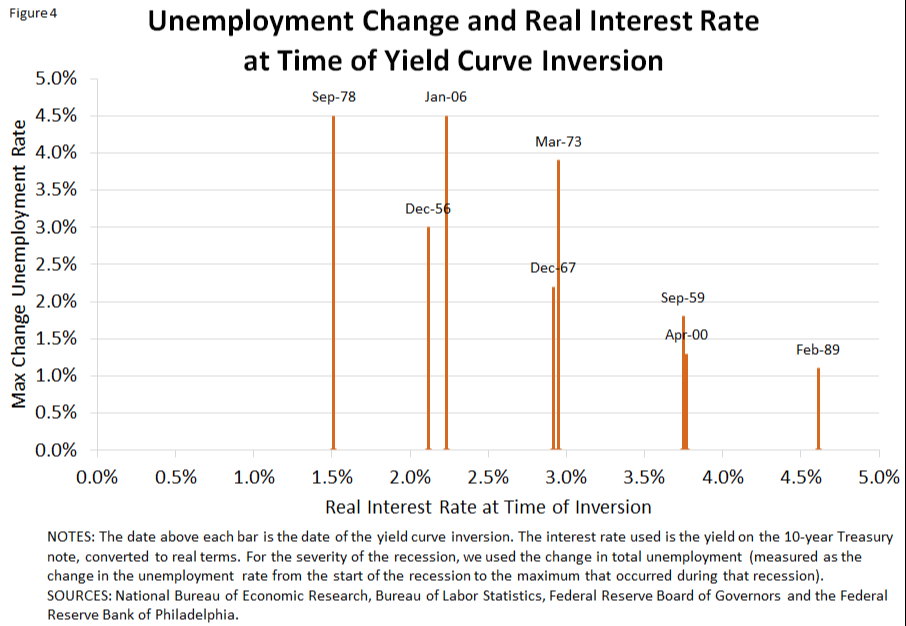

The authors looked at all the postwar recessions that the yield curve had predicted. Then they looked at the 10-year Treasury yield at the moment of inversion—and compared it with the length of the subsequent recession.

At first glance, this revealed nothing: Nominal rates at these critical turning points had no correlation with the economy’s decline. But when they looked at the real interest rate—the 10-year yield minus inflation—they found something else altogether.

Lower real rates for 10-year Treasuries at the onset of a recession tracked with worse downturns, both in terms of duration and unemployment.

Explaining the connection is another matter. While it’s tempting to read this as a causal relationship, the researchers speculate that lower real rates are simply a sign that the prospects for future growth aren’t great. As they put it, “Low levels of real interest rates capture early warnings of future slowdown in economic growth.”

This makes considerable sense if you think about the past 10 years. Yes, the economy made a recovery, but only through staggering levels of intervention via a zero interest rate policy. For all the talk about the duration of the ongoing recovery, the fact that short- or long-term interest rates haven’t bumped higher is a symptom of a deeper malaise.