If health means wealth, as the adage has it, then America’s economic future looks grim. Traditionally, the U.S. has enjoyed a health premium. In the Colonial era, American men were on average two to three inches taller than Europeans, according to military records, a fact that fascinates historical demographers because height is correlated with longevity, cognitive development and work capacity. Today, a premium is turning into a deficit. American men are shorter on average than Northern European men, and the gap is getting bigger. Six in ten Americans suffer from at least one chronic condition and four in ten suffer from two. “America is a sick society,” says William Galston in the Wall Street Journal. “Literally.”

America’s health deficit is a growing economic problem. The labor force participation rate is a dismal 62.4%: 11 million jobs are vacant, compared with just 5.7 million people who are looking for work, according to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, and 2.8 million people have disappeared from the workforce since February 2020. Employers complain about absenteeism and job-churn as well as their inability to fill jobs. Health-care costs head ever upward. At a time of growing tensions with both Russia and China, the health deficit is also a national security problem. A 2020 survey for the Pentagon found that more than three-quarters of young Americans (18-24) were unfit for military service due to health problems, with obesity the most prominent among them.

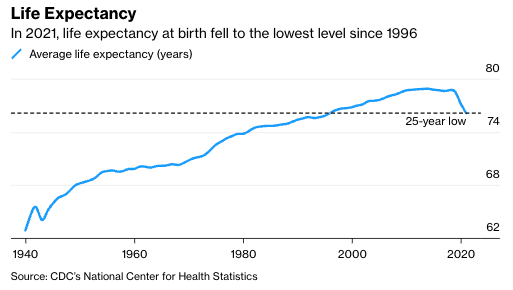

The most vivid sign of the health crisis is falling life expectancy. We have long assumed that modernity brings longer life—indeed, that longer life is proof that all that creative destruction is worth it after all. That has not been the case in the U.S. since 2014. In 2021, life expectancy fell to 76.1 years—the lowest figure since 1996, erasing a quarter century of progress. Other advanced countries are pulling further ahead—Germans could expect to live 4.3 years longer than Americans in 2021 compared with 2.5 years in 2018 and the French six more years compared with four years in 2018. West Virginia’s life expectancy is lower than Mexico’s.

The U.S. has one of the highest rates of obesity in the advanced world, a rate that has increased from 15% in 1980 to 30.5% in 2000 to 41.9% in 2020. This is ten times the rate in Japan and significantly higher than China. Obesity is linked to multiple health problems, including heart disease, depression, hypertension, lifestyle related cancer and diabetes, which afflicts 13% of the population and costs U.S. employers an estimated $90 billion a year.

The obesity problem is significantly worse in a cluster of southern and southeastern states (Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee and Texas) that have strong military traditions. It is also worse in the working class and in Black and Hispanic populations (the figures for Asians are more complicated because there is such a difference between Southeast Asia and the Indian subcontinent). A 2020 study put the economic cost of obesity at almost $1.4 trillion for 2018—almost 7% of the gross domestic product.

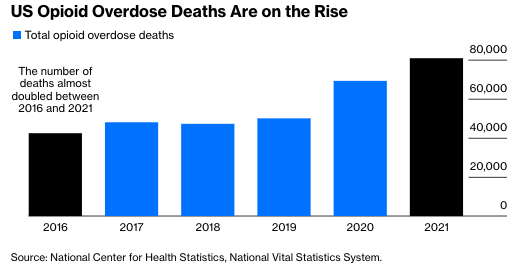

The opioid epidemic turbocharged America’s problems with drug- and alcohol-abuse. Deaths from drug overdoses rose from 17,000 (62 per million) in 2000 to 92,000 (277 per million) in 2020, largely driven by the mass production and distribution of opioids by big pharmaceutical companies. Unsurprisingly, opioid abusers are more likely to take unscheduled leaves or drop out of the workforce entirely as well as to die prematurely.

The opioid epidemic may have taken root in populations that already had health problems: The vast majority of opioids were originally prescribed to people who want relief from pain caused by either disability or illness. The epidemic is certainly more concentrated in certain classes and areas where repetitive physical work is a way of life: Death rates from overdoses are five to seven times higher for those without a college degree than for those with one and much higher in ex-coal mining communities, particularly in Appalachia, than elsewhere.

The Covid-19 pandemic acted as the third horseman of the health apocalypse. America’s Covid death rate is still much higher than in most other advanced countries, with 339 deaths per 100,000 population compared with 254 in France, 201 in Germany and 134 in Canada, thanks to the country’s poor primary healthcare system.

The pandemic led to a sharp decline in America’s (already low) labor force participation rate, a decline from which the country has still not recovered. It also seems to have left a longer-term legacy in terms of “long Covid,” a problem that doctors are still trying to understand but which leaves people with problems such as fatigue, shortness of breath, and brain fog. The Brookings Institution suggests that some three million people—or 1.8% of the civilian labor force—may be out of work due to long Covid, representing $168 billion in lost annual earnings.

Covid has also exacerbated obesity and addiction-related problems. Overweight people are more likely to die from Covid or suffer enduring consequences than thin ones. The Covid epidemic acted as a national pusher for addictive substances, with the number of overdose deaths for opioids, methamphetamine and even alcohol surging during the pandemic. One 2022 study suggests that increased substance abuse during the pandemic accounts for between 9% and 26% of the decline in prime-age labor force participation between February 2020 and June 2021.

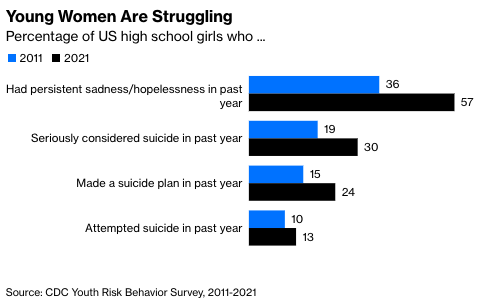

Uncle Sam’s mental health problems seem to be as pressing as his physical health problems, though they are clearly harder to measure and diagnose. A Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report shows that in 2021 nearly a third of high school girls seriously considered taking their own lives. Young men suffer from an epidemic of alienation with increased dropout rates from school and falling rates of attendance for university. None of this bodes well for the future.

If all this is having an adverse effect on the U.S. workplace, the U.S. workplace may also be having an adverse effect on the health of the workforce. This is particularly true of blue-collar and frontline workers—that is, the people who operate in the physical world rather than the virtual one, making things or delivering packages. At best, American managers are guilty of ignoring the needs of frontline workers while living in a bubble of fellow managers. At worst, they have been squeezing them to work ever harder in what are already monotonous jobs. The epidemic of quitting such jobs is partly because people find them so unforgiving but partly because they suffer from health problems themselves, or else must look after family members who suffer from health problems.

What can be done about all this? Addressing America’s health-care crisis is even more difficult than addressing declining educational standards. The fast-food industry is a powerful lobby determined to stuff the population (particularly the poor) with saturated fat and salt while whispering sweet nothings about ESG. The health-care industry is a mass of malign vested interests and skewed incentives. The left’s reluctance to blame the victim has left people (including doctors) unwilling to say the obvious—that obesity is generally caused by eating too much and moving too little. The right’s instinctive loathing of government busy-bodying makes it difficult to deliver even the most basic advice on the foolishness of drinking a gallon of sugar-laden soda.

Still, hard does not mean impossible. America took on the once mighty tobacco industry and won: The U.S. has lower rates of cigarette smoking than other advanced countries, particularly in southern Europe, where people still puff away over their meals. In the early 20th century, the British realized that they could not preserve their position as Europe’s leading economic and military power against a rising Germany unless they did something about the poor health of the population—as Lloyd George put it, “you cannot conduct an A1 Empire with a C3 population.” A reforming Liberal government waged war against adulterated food, established a school health service and splashed out on free school milk (“there is no finer community than putting milk into babies,” said Winston Churchill, who was then a Liberal).

Americans need to apply the same determination to the fight against junk food that they brought to the fight against tobacco. They also need to start thinking about the condition of the population in the same hard-headed way that Britain’s early 20th-century liberals did, as a matter of national efficiency as well as national compassion. Good health is not just something that is nice to have. It is a vital component of national competitiveness. And poor health is not just a tragedy for the individual who suffers from it. It is, in aggregate, a constraint on the country’s productivity and ability to defend itself.

Adrian Wooldridge is the global business columnist for Bloomberg Opinion. A former writer at the Economist, he is author, most recently, of The Aristocracy of Talent: How Meritocracy Made the Modern World.

This article was provided by Bloomberg News.