After the disease, the debt. After the plague, the pile of IOUs. It is a veritable mountain — a reminder that the original public debt in medieval Venice went by the name monte. According to the International Monetary Fund’s October Fiscal Monitor, the Covid-19 pandemic and associated lockdowns have prompted a plethora of fiscal measures amounting to $11.7 trillion, around 12% of global GDP — and that number has probably risen since it was calculated on Sept. 11. “In 2020,” according to the Fund, “government deficits are set to surge by an average of 9 percent of GDP, and global public debt is projected to approach 100 percent of GDP, a record high.”

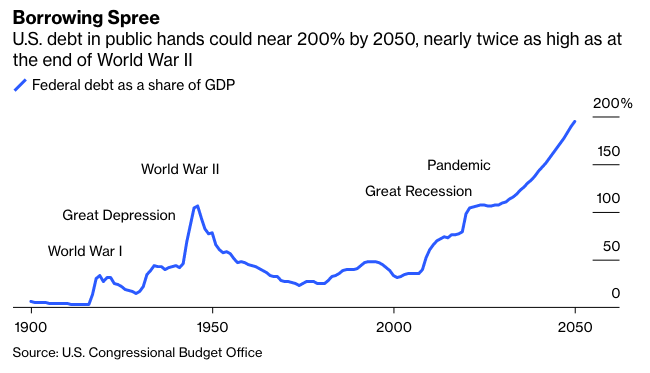

In advanced economies, public debt relative to output has increased as much since the late 1970s as it did between 1914 and 1945. Together, the global financial crisis and the pandemic have had roughly the same doubling effect as World War II. While Covid-19 will not kill as many people globally as history’s biggest war, the ultimate U.S. death toll is very likely to be higher. The pandemic’s financial cost also looks similar to that of a world war.

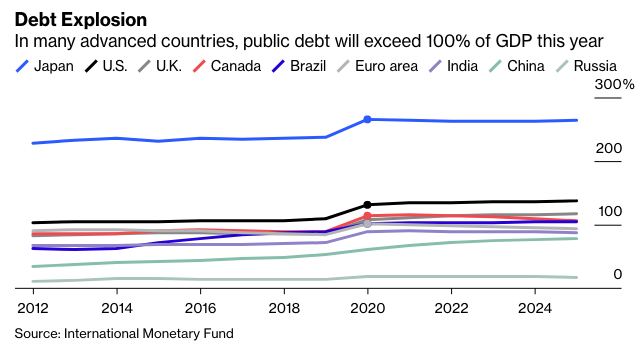

The IMF’s global averages conceal huge variations between countries. The deficits of seven developed countries — Canada, the U.K., the U.S., Brazil, Italy, Spain and Japan — have each risen by more than 10% of GDP. In all these countries, gross public debt will exceed 100% of GDP this year, with Japan’s reaching 266%. The IMF’s projection for U.S. gross debt is 131%.

Because the Federal Reserve has purchased most of the new Treasury bonds created this year, the increase in the federal debt held by the public is not so daunting (The federal debt held by the public excludes bonds held by federal trust funds such as Medicare and Social Security, but includes bonds bought by the Federal Reserve). The Congressional Budget Office projects that it will be just under 100% this year (98.2%), but that is still nearly three times what it was at the beginning of this century. Next year it is forecast to surpass the level in 1945.

But the story doesn’t end there, because the federal government is expected to keep borrowing as far as the eye can see, with the deficit rising inexorably from 4% in the late 2020s to over 12% by mid-century. The CBO’s baseline projection is for the federal debt in public hands to reach 195% of GDP by 2050, nearly twice as high as at the end of World War II.

Historically, large public debts have had a terrible reputation. In his “Rural Rides,” which he began in 1822 and published in 1830, the English radical William Cobbett inveighed against the vast national debt incurred during the Napoleonic Wars. The political purpose of the debt, Cobbett argued, had been “to crush liberty in France and to keep down the reformers in England” but its principal effect after the war was redistributive. “A national debt, and all the taxation and gambling belonging to it, have a natural tendency to draw wealth into great masses … for the gain of a few.”

“The Debt, the blessed Debt,” he continued, was “hanging round the neck of this nation like a millstone.” It was a “vortex,” sucking money from the poor to a new plutocracy.

Cobbett was not wrong. According to the best estimates from the Bank of England, Britain’s wars between 1776 and 1815 drove up the debt/GDP ratio from 86% to more than 172% by 1822. In those days, government bonds were almost entirely owned by a tiny wealthy elite, while taxation was largely indirect, on imports and consumption, and therefore highly regressive. Moreover, real (inflation-adjusted) long-term interest rates were strongly positive, averaging 5.27% in the 1820s.